Cricket

This article or section is currently being expanded by an editor. You are welcome to help in expanding too. If this page has not been changed in several days, please remove this template. This article was last edited by BlackJack (talk | contribs) 2 months ago. |

The pale area of the field is the pitch, with a wicket in place at each end. The batter (Gilchrist) is using his bat to defend the wicket against the white ball which Murali has just bowled. Sri Lanka's wicket-keeper (#11) is crouching just behind the wicket which Gilchrist is defending. The other Sri Lanka player (#55) is a fielder operating in the "first slip" position. Gilchrist's partner, the "non-striker", stands by the other wicket at the bowler's end of the pitch. Behind that wicket stands one of the two umpires. The lines on the pitch are the various creases.

Cricket is a sport. It is an outdoor bat-and-ball game played by two teams of eleven players on a large, grassy field. At the centre of the field is a rectangular pitch with a wooden structure called a wicket sited at each end. As in other sports, there are separate men's and women's games, both played internationally.

In all levels of cricket, the essence of the game is that the wicket is a target being attacked by a bowler using the ball, and defended by a batter using a bat. The bowler is a member of the fielding team; the batter is a member of the batting team. The objective of the batting team is to score as many runs as possible. The objective of the fielding team is to restrict scoring and, by various means, dismiss the batters. If ten batters are dismissed, the batting team is all out and the teams change roles. Generally, the winning team is the one scoring the most runs, although some matches can result in a draw or, occasionally, a tie.

Probably created as a children's game in south-east England, cricket is known to have been played in the mid-16th century. It has expanded to become the national summer sport of several English-speaking countries. Matches range in scale from informal weekend afternoon games played on village greens to top-level international contests played by professionals in modern, all-seater stadiums. Globally, the sport has a high level of player participation and is, apart from football, the world's most popular spectator sport.

The Laws of Cricket

[change | change source]

Like all other sports, cricket has rules and regulations. These are called The Laws of Cricket, a code which was first written in 1744, and first published in November 1752.[1][a] There was a significant revision in 1774.[3]

Copyright of The Laws is held by Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), founded in 1787, which issued a revised version on 30 May 1788.[4] Although MCC still has responsibility for drafting and publishing revisions, it does so in consultation with the sport's governing body, the International Cricket Council (ICC), which has over 100 member countries. Following the 2017 revision, there are now 42 Laws headed by a preamble on the "Spirit of Cricket".[5]

The field

[change | change source]The cricket field is of variable size and shape, though normally round or oval with a diameter of 140 to 160 yards. Professional venues tend to have names including Ground, Oval, Park, or Stadium. There are several famous Ovals, especially The Oval in the Kennington district of south London; Kensington Oval in Bridgetown, Barbados; and the Adelaide Oval. Among the Grounds are the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG), and the Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG). Sabina Park is a famous venue in Jamaica. The Narendra Modi Stadium in Ahmedabad seats 132,000 and is the world's largest sports stadium.[6]

The playing field's perimeter is known as the boundary.[7] It is often defined by a rope encircling the outer edge of the playing area, with spectator seating beyond. During play, a shot by the batter which clears the boundary on the full is worth six runs—this is similar to a home run in baseball. A shot which reaches the boundary after the ball has been in contact with the ground is worth four runs, and that is often called "scoring a boundary".[7] One of the most famous books written about cricket is Beyond A Boundary by the radical Trinidadian writer, C. L. R. James.[8]

The pitch

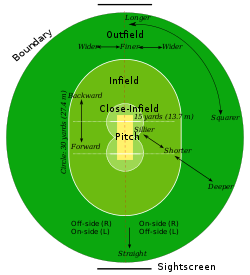

[change | change source]Most of the action in a match takes place on the pitch, a specially prepared rectangular area of the field on which the wickets are sited and creases are painted as shown in the diagram below.

The pitch is 22 yards long (the length of an agricultural chain) between the wickets and is ten feet wide. It is a flat surface and has very short grass that tends to be worn away as the game progresses. As can be seen in the above photo of Murali bowling to Adam Gilchrist, the pitch is always much paler than the main part of the field.[9]

Pitch conditions have a significant bearing on the match and team tactics are always determined with the state of the pitch, both current and anticipated, as a key factor. Groundsmanship is very important in cricket as considerable care — mowing, watering, and rolling — is necessary to prepare and maintain pitch surfaces. In addition, there are rules about covering the pitch during a match when bad weather occurs.[10]

The wickets

[change | change source]Sited at each end of the pitch is a small structure called the wicket. Made entirely of wood (usually polished ash), a wicket consists of three upright stumps placed in a straight line and surmounted by two horizontal bails which are placed across the two gaps. The dimensions of a wicket are 28.5 inches high by 9 inches wide.[11]

The creases

[change | change source]Creases are painted lines at both ends of the pitch. There are three types of crease, and each has a special purpose. As can be seen in the diagram above, the stumps at each end are aligned in the centre of the bowling crease, which is 8 feet 8 inches long. Parallel with the bowling crease, and four feet forward of it, is the popping crease. This marks the limit of the batter's "safe territory", and is where the batter stands when "taking guard" while the ball is being bowled. The popping crease and the return creases define the area within which the bowler must complete delivery. As the bowler releases the ball, the back foot must land within the two return creases, and the front foot must land on or behind the popping crease.[12]

Umpires and scorers

[change | change source]A match is controlled on-field by two umpires. One of the umpires stands behind the wicket at the bowler's end, and the other stands in a fielding position called "square leg" (see the fielding positions diagram), which is directly in line with the striker's wicket and about fifteen yards from it. The umpires switch positions at the end of each over. In televised matches, particularly those played at international level, there is often a "third umpire" who can make decisions on certain incidents with the aid of video evidence.[13]

Off the field, the match details including runs and dismissals are recorded by two scorers, one from each team.[14]

Equipment

[change | change source]The key pieces of equipment needed to play a game of cricket are the bat and the ball. At its most basic level, cricket involves a bowler bowling a ball at a target that is defended by a batter, who uses a bat to stop the ball or hit it away. Because cricket is a dangerous game, wearing protective gear is also necessary.

The bat

[change | change source]

A cricket bat is made of wood (usually willow) and takes the shape of a straight blade topped by a cylindrical handle. The blade must not be more than 4¼ inches wide and the total length of the bat not more than 38 inches.[15]

The ball

[change | change source]A cricket ball is a rock-hard leather-seamed spheroid projectile with a circumference limit of nine inches. It can be delivered by the fastest bowlers at speeds of more than 90 mph and so the batters and the wicket-keeper wear protective gear, as do fielders who occupy positions in close proximity to the batter. In Test and first-class cricket, the ball is red; in limited overs matches, it is white.[16]

Protective gear

[change | change source]Batters wear pads (designed to protect the knees and shins), reinforced batting gloves, a safety helmet and a box. Some batters wear additional padding inside their shirts and trousers such as thigh pads, arm pads, rib protectors and shoulder pads.[17]

The wicket-keeper wears pads and specially reinforced gauntlets to protect the legs and hands respectively.[18] Close fielders may wear a helmet but are not allowed to wear gloves.[19]

Innings

[change | change source]The captains

[change | change source]Each team is led by its captain (aka the "skipper"), who is often the most experienced player. Cricket is an intensely strategic sport and the captain, bearing responsibility for leadership and team tactics, is the most important member of the team, especially when fielding, though other senior players are usually consulted before any tactical decision is made. Among the captain's considerations are the current and expected pitch and weather conditions.

The toss

[change | change source]Before play commences, the two team captains meet on the pitch and toss a coin to decide which team shall bat or field first. The toss is regulated by Law 13.4, which states that at least one umpire must be present and that it must be done at least fifteen, but not more than thirty, minutes before play is scheduled to begin. The captain who wins the toss must decide whether to bat or field in the first innings of the match, and immediately announce the decision.[20]

The innings

[change | change source]A match is divided into phases known as innings (the same spelling is used for both singular and plural) and, depending on the type of match, there may be two or four innings, as defined in Law 13.[20] In each innings, while one team is batting, the other is fielding, and a key member of the fielding team is bowling. Throughout an innings, all eleven members of the fielding team are on the field, but only two batters. When the batting team's innings has been completed, the teams reverse roles for the next innings, the fielding team becoming the batting team and vice-versa. The match ends when all innings have been completed.

A batter when dismissed is ruled to be "out", and the umpire calls this. When a batter is out, they are replaced by one of their team-mates. The innings ends when ten of the eleven batters are out: i.e., the team is "all out". One batter remains but cannot play alone, and so is "not out". In a first-class match, the innings can end early if the captain of the batting team decides to declare the innings closed for tactical reasons before the batters are all out. In limited overs matches, the innings ends after the prescribed number of six-ball overs have been bowled.

Overs

[change | change source]The bowler bowls the ball from one end of the pitch to the batter (the striker) defending the wicket at the other end. Every time a bowler bowls the ball, they are said to have completed a delivery or, more simply, a ball. The bowler must complete the delivery with a straight arm, and must ensure that their feet are within bounds set by the creases, as described above.

When the bowler has completed six successive deliveries, the umpire at that end of the pitch calls "Over!" and each set of six deliveries by one bowler is thus called an over. If the bowler does not concede any runs in the over, that over is termed a maiden and bowlers are credited with these in their career statistics. On completion of an over, the fielding team changes ends, and the two umpires swap roles. The next over begins with a different bowler operating from the other end, and bowling to the batter who was the non-striker at the end of the previous over. A bowler cannot operate from both ends consecutively but will usually bowl every other over from the same end through several overs until completing a "spell" and the captain replaces them with another bowler. It follows that two bowlers are often deployed "in tandem". When a bowler completes an over, they stay on the field and become one of the fielders until they bowl again.

Fielding

[change | change source]

All eleven players on the fielding side take the field together. One of them is the wicket-keeper, a specialist who operates behind the wicket being defended by the batter on strike. Besides the bowler and the wicket-keeper, the other nine fielders are tactically deployed by the team captain in chosen positions around the field, except as stipulated in Law 28.5 that they are not allowed to stand on the pitch.[21]

The fielding positions are not fixed but they are known by specific and sometimes colourful names such as third man, silly mid on, and long leg. The captain determines all the tactics including who should bowl (and how); and is responsible for setting the field, though usually in consultation with the bowler. The fielding team is allowed substitutes in case of injury or other valid reasons for a player's absence, subject to Law 24 which stipulates that a substitute is not allowed for a fielder who leaves for other than "a wholly acceptable reason".[22]

Bowling

[change | change source]Any of the eleven fielders can bowl but it is extremely rare, though not unknown, for the wicket-keeper to bowl. Generally, the only players in the fielding side who will actually bowl are those recognised for their ability as bowlers, including any all-rounders who are adept at both batting and bowling. Players selected as specialist batters bowl only occasionally.

Bowlers are classified according to their speed or method of delivery. The main types of bowling are fast bowling, swing bowling, seam bowling and spin bowling. The latter is sub-divided into types of spin: off break (off spin), leg break (leg spin) and googly for right-arm spinners; orthodox and unorthodox (unorthodox was historically termed "chinaman" because Ellis Achong, who invented the style, was of Chinese descent) for left-armers. The classifications, as with much cricket terminology, can be very confusing. They are often written in abbreviated form: for example, LF is a left arm fast bowler, RM is a right arm medium paced seam bowler, and LBG is a right arm spinner who bowls deliveries that are called a leg break and a googly.[source?]

The bowler reaches his delivery stride by means of a "run-up". A fast bowler needs momentum and takes quite a long run-up, usually running very fast as he does so. Bowlers with a very slow delivery take no more than a couple of steps before bowling. The fastest bowlers can deliver the ball at a speed of over 90 mph and they usually rely on sheer speed to try and defeat the batter, who is forced to react very quickly to a ball that reaches him in an instant. The Australian fast bowler Jeff Thomson, who played in the 1970s, was a classic example of this type of bowler. The generally accepted world record for the fastest recorded delivery of a cricket ball is 100.23 mph by Shoaib Akhtar at Cape Town's Newlands Cricket Ground in February 2003.[source?]

Other fast bowlers rely on a mixture of speed and guile. Some make use of the seam of the ball so that it curves or swings in flight and this type of delivery, called swing bowling, can deceive a batter into mistiming his shot so that the ball touches the edge of the bat and can then be caught behind by the wicket-keeper or by a slip fielder. The great England fast bowler Fred Trueman, who played in the 1950s and 1960s, was a brilliant exponent of the "outswinger", which moves away from the batter in flight. Other bowlers use the "inswinger", which deviates towards the batter.[source?]

At the other end of the bowling scale is the spinner who bowls at a relatively slow pace and, with the spin he imparts onto the ball, relies entirely on guile to deceive the batter. A spinner will often buy his wicket by "tossing one up" to lure the batter into making an adventurous shot. The batter has to be very wary of such deliveries as they are often flighted or spun so that the ball will not behave quite as he expects, and he could be trapped into getting himself out. Two great spin bowlers have operated in 21st century cricket: Shane Warne of Australia and Muttiah Muralitharan of Sri Lanka. Off spinners and orthodox left armers utilise finger spin in their deliveries; leg spinners and unorthodox left armers utilise wrist spin.[source?]

In between the pacemen and the spinners are the medium-paced seam bowlers (or seamers) who rely on persistent accuracy to try and contain the rate of scoring and wear down the batter's concentration. These bowlers are classified by arm as LM or RM.[source?]

It is generally held that the greatest bowler of all time was Sydney Barnes, whose versatility was extraordinary. Barnes was ostensibly a right arm medium pace bowler but he varied his pace from slow to fast medium. Always noted for his control of length and direction, he had a mastery of swing. He used both outswing and inswing to great effect, and he could also produce either a leg break or an off break.[source?]

Batting

[change | change source]While awaiting delivery of the ball, the striker adopts a stance called "taking guard". The striker must quickly decide which shot to play by judging the flight and speed of the ball, taking into account where and how it is expected to hit the pitch, and how it will behave after it has pitched. The striker's partner, the non-striker, stands by the other wicket at the bowler's end of the pitch, as can be seen in the Murali/Gilchrist photo above. The other nine members of the batting team are off the field in the pavilion. If the striker plays a scoring shot and decides to run, the non-striker must be ready to run too.[source?]

Depending on the quality of the delivery received, the striker may play defensively without attempting to score a run. If an offensive shot is played to hit the ball away from the pitch and clear of the fielders, then the two batters have the option to run to the other end of the pitch without one of them being run out. Completing a run is the means of scoring in cricket. Each run is added to the team total and to the striker's personal total.[source?]

A skilled batter can use a wide array of strokes (also called shots) in both defensive and attacking mode. Cricket is very fond of naming things, as with the field placings, and each shot or stroke in the batter's repertoire has a name too: e.g., "cut", "drive", "hook", "pull", etc. The idea is to hit the ball to best effect with the flat surface of the bat's blade. Batters do not always seek to hit the ball as hard as possible and a good player can score runs just by making a deft stroke with a turn of the wrists or by simply blocking the ball but directing it away from fielders so that there is time to take a run.[source?]

A batter does not have to play a shot and can "leave" the ball to go through to the wicket-keeper, providing it will not hit the wicket. Equally, the batters do not have to attempt a run when the ball has been hit with the bat, and some batters will tactically play defensively and without scoring, known as "stonewalling", for long periods of time. The striker can deliberately use a leg to block the ball, and thereby "pad it away", but this is risky because of the leg before wicket (lbw) rule.

If a batter retires (usually due to injury) and cannot return, the retirement does not count as a dismissal because the batter was "not out". In effect, however, it is a dismissal because the innings is over. Substitute batters are not allowed, but the rules do allow a "runner" (a third batter) to come on for running purposes only if one of the batters is injured and, although able to take strike, cannot run. There are special rules concerning the deployment of runners.[source?]

The batters do not change ends at the end of an over and so, like the umpires, their roles are interchangeable; the one who was the striker when the previous over ended is now the non-striker, and vice-versa.[source?]

Runs

[change | change source]One run is commonly called a single. Hits worth one to three runs are common, but the size of the field is such that it is usually difficult to run four or more. To compensate for this, hits that reach the boundary of the field are automatically awarded four runs, if the ball makes contact with the ground en route to the boundary, or six runs if the ball clears the boundary on the full.

Hits for five are unusual and generally rely on the help of an overthrow by a fielder returning the ball to the bowler or wicket-keeper. If an odd number of runs is scored by the striker, the two batters have changed ends and the one who was non-striker is now the striker for the next delivery. Only the striker can score individual runs but all runs are added to the team's total.

If a batter scores a "half-century" of fifty runs, it is considered a good performance that will earn a round of applause. Scoring one hundred runs, referred to as a "century", is a noted achievement. Scores of 200 and 300 are not uncommon and these are called "double-centuries" and "triple-centuries" respectively. Failure to score at all is something no batter wants. A score of zero is called a "duck" and, if it happens in both innings of the same game, the batter is said to have "bagged a pair" (i.e., of spectacles – two zeroes).

While two batters are "in" together, they are sharing a partnership, and match records always note how many runs are scored while a partnership lasts. If, for example, the first four batters are out and it is the fifth and sixth batters in the batting order who are in together, and they add 100 runs to the team total before one of them is out, the record will show that they shared a "century partnership for the fifth wicket".

Extras

[change | change source]Additional runs can be gained by the batting team as extras (aka sundries) by courtesy of the fielding side. This is achieved in four ways:

- No ball

- A penalty of one extra that is conceded by the bowler for breaking the rules of bowling either by (a) using an inappropriate arm action; (b) overstepping the popping crease; (c) having a foot outside the return crease.

- Wide

- A penalty of one extra that is conceded by the bowler if the ball is bowled so that it is out of the batter's reach.

- Bye

- Extra(s) awarded if the batter makes no contact with the ball, and it goes past the wicket-keeper to give the batters time to run in the conventional way (note that one mark of a good wicket-keeper is the ability to restrict the tally of byes to a minimum).

- Leg bye

- Extra(s) awarded if the batter does not hit the ball with the bat, or with the hand holding the bat, but the ball strikes another part of the body (not only the leg), and goes away from the fielders to give the batters time to run in the conventional way.

When the bowler has bowled a no ball or a wide, the fielding team team incurs an additional penalty because that delivery has to be bowled again, and hence the batting side has the opportunity to score more runs from this extra ball. The batters have to run, unless the ball goes to the boundary for four, to claim byes and leg byes but these only count towards the team total, and to the extras, not to the striker's individual total for which runs must be scored off the bat. For a leg bye to count, the umpire must be satisfied that the batter was trying to play a shot, or was trying to avoid being struck by the ball.

Dismissals

[change | change source]There are several ways in which a batter can be dismissed and some are so unusual that only a few instances of them exist in the whole history of the game. The most common forms of dismissal are bowled, caught, leg before wicket (lbw), run out, and stumped. These are respectively denoted on scorecards as "b", "c", "lbw", "run out" and "st". Apart from a run out, the dismissal is always credited to the bowler as well as, where appropriate, the fielder or wicket-keeper. The unusual types of dismissal are hit wicket, hit the ball twice, obstructed the field, and timed out.

Appeals

[change | change source]Before the umpire will award some dismissals and declare the batter to be out, a member of the fielding side (generally the bowler) must appeal. This is invariably done by asking (or shouting) the term "Owzat?" which means, simply enough, "how's that?" If the umpire agrees with the appeal, they will raise a forefinger and say "Out!" Otherwise, they will shake their head and say "Not out".

There have been many cases of umpires not being able to rule a batter out because the fielders did not appeal, even though the umpire was in no doubt about the dismissal. Appeals are particularly loud when the circumstances of the claimed dismissal are unclear, as is always the case with lbw and often with run outs and stumpings. It is usually the striker who is out when a dismissal occurs but the non-striker can be dismissed by being run out.

The cricket ground

[change | change source]Care and maintenance of the pitch and turf are very important in cricket, and this is the responsibility of the groundsman whose duties may extend towards the entire ground or stadium, not just the playing area. Assisting the groundsman are the groundstaff who are club employees, mainly junior players.

Originally, cricket was played on whatever surface was available, providing the grass had been cropped short enough by sheep. Pitch preparation was limited to removing stones and stamping on divots. Through the eighteenth and well into the nineteenth century, preparation was rudimentary at best and the pitches were completely exposed to the elements.

Heavy rollers for flattening turf were first used at Lord's in 1870 and it is generally agreed that this was the innovation that began the improvement in pitches.[23] Later still, in 1895, groundsmen began using marl, a sort of limestone clay that binds the soil (it is also used as fertiliser) and ensures more permanence in the surface.[24] As the twentieth century began, the rough tracks of the past began to disappear.[24]

Apart from rollers, one of the most important pieces of equipment used by the groundstaff is the pitch cover which can best be described as a long, low bogie that has a roof-shaped upper section to which drainage hoses are attached. This is wheeled out onto the field whenever rain stops play and is placed over the pitch and surrounded by huge pieces of plastic sheeting which effectively cover the whole of the infield area including the bowlers' run-ups. The field can still become very wet despite all of this protection and it is not unusual to see bowlers pouring sawdust into wet patches where they tread during run-up.

The groundstaff are also responsible for maintaining and positioning the sightscreens, which are hoardings just off the field and directly behind each wicket. They provide a clear background for the batter to sight the ball in the bowler's hand and so see it clearly through delivery. A white sightscreen is used in daytime when a red ball is in use and a black screen in a night match when a white ball is used. Many grounds have practice pitches in their outfields, well away from the playing pitches, and these are enclosed on three sides by nets so that the ball is contained in the practice area unless the batter plays a straight hit past the bowler.

Other features of the cricket ground are the pavilion and the scoreboard. The players' dressing rooms are located inside the pavilion which is the club's headquarters. Some very large pavilions, like the one at Lord's, can serve as grandstands. Scoreboards are erected as an information aid for spectators and frequently form the frontage of a building. The match score is updated after each delivery and the board also provides information about the current batters and bowlers. A basic scoreboard is operated manually but international stadiums often have electronically operated boards.

Now, cricket is played in high-class stadiums. The Narendra Modi Stadium in Ahmedabad seats 132,000 and is the world's largest sports stadium.

Origin and development of cricket

[change | change source]According to John Major in More Than A Game, cricket is "a club striking a ball (like) the ancient games of club-ball, stool-ball, trap-ball, stob-ball". As he says, each of these have at times been described as early cricket.[25] It is generally believed that cricket began as a children's game in the south-eastern counties of England sometime before the sixteenth century.[26]

Types of match and competition

[change | change source]Cricket is a multi-faceted sport. The Laws allow for many variations of contest and competition according to duration, location, timing, playing standards, qualification and other factors. In very broad terms, cricket can be divided into matches in which the teams have two innings apiece and those in which they have a single innings each. The former has a duration of three to five days (in earlier times there were timeless matches too); the best-known form of the latter, known as limited overs cricket (or one-day cricket) because each team bowls a limit of typically 50 overs, has a planned duration of one day only (a match can be extended if necessary due to bad weather, etc.). Historically, a form of cricket known as single wicket was extremely popular and many of these contests in the 18th and 19th centuries qualify as top-class matches. Single wicket has rarely been played since limited overs cricket began.

Test cricket

[change | change source]Test cricket is the highest standard of cricket. A Test match is an international fixture, invariably part of a series of three to five games, between two international teams that have full member status within the International Cricket Council (ICC). The teams have two innings each, and the match lasts for up to five days with a scheduled six hours of play on each day (this varies if there are interruptions due to the weather, or if an agreed number of overs is not completed within the six hours).

Men's Test cricket began with Australia versus England in 1877, although the early Tests were in fact classified as such retrospectively. Women's Test cricket began in 1934, again with Australia Women hosting England Women.

Subsequently, ten other countries have achieved men's Test status: South Africa (1889), West Indies (1928), New Zealand (1929), India (1932), Pakistan (1952), Sri Lanka (1982), Zimbabwe (1992), Bangladesh (2000), Afghanistan (2017), and Ireland (2017). The West Indies is a federation whose team is made up of players from nations including Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Trinidad & Tobago, the Leewards and the Windwards. England is actually England and Wales combined (Scotland is separate, although many Scots have played for England); similarly, Ireland is an all-Ireland combination. In women's cricket, the teams that have played Test matches are Australia Women, England Women, India Women, Netherlands Women, New Zealand Women, South Africa Women and West Indies Women.

First-class cricket

[change | change source]Test cricket is a form of first-class cricket. This term, which has an official definition, is generally used in reference to the highest level of domestic cricket, especially in the Test-playing nations. National championships, such as the English and Welsh County Championship, are first-class competitions. A first-class match has a duration of three to five days, the teams having two innings each.

The draw is a possible result in first-class matches and this happens if playing time expires while the losing team is still batting (in other words, if the team batting last have not reached their target total and are not all out when time is up). Another feature of first-class matches is the follow-on, whereby the team batting second can be asked by the fielding captain to bat again in the third innings if they have been dismissed for a total that is over 150 less (200 less in a Test) than the first innings score of their opponents. This, in turn, can lead to an innings defeat if the team following on are all out for another low score and the combined totals of their two innings is less than that scored by their opponents in one innings.

Limited overs

[change | change source]A One Day International (ODI), also called a Limited Overs International (LOI), is the highest standard of limited overs cricket. In men's cricket, as well as the countries that play Test matches, this class includes those that have ICC associate member status, although they rarely play against the Test teams. Prominent associate members are Bermuda, Canada, Kenya, Namibia, Nepal, Netherlands, Scotland, and the United States. The ICC Women's Cricket World Cup was inaugurated in 1973, and the ICC Men's Cricket World Cup in 1975. Women's teams playing in LOIs, in addition to the seven Test countries, are Bangladesh Women, Pakistan Women, and Sri Lanka Women.[source?]

Limited overs matches are scheduled for a single day but they can be extended if necessary due to bad weather. Each team has one innings and the overs limit is usually fifty per side. There are various competitions in domestic cricket, beginning in England with the Gillette Cup knockout in 1963. There is no draw result except in the form of a tie, when the scores are level, or a no result due to rain or other factors.[source?]

Twenty20

[change | change source]Twenty20 (T20) is a variant of limited overs in which each team has twenty overs. The match lasts two to three hours and so can be fitted into an evening. It was introduced into English cricket in 2003 and has become extremely popular in India where the Indian Premier League (IPL) is contested. The Twenty20 International (T20I) was soon introduced, and there is an ICC Men's World Twenty20 Championship, first held in 2007, and an ICC Women's World Twenty20 Championship, first held in 2009.[source?]

National championships

[change | change source]These are held in each country and the matches are the main instances of first-class cricket. For example, England and Wales have the County Championship which has tentative origins stretching back to the 1720s, and was formally organised as an official competition in 1890. Since 2000, it involves 18 county teams who are split into two divisions. Each team plays the other eight in its division, both home and away, in double innings fixtures with a duration of up to four days. The championship teams are all run by county clubs, of which the oldest was founded in 1839 to manage the Sussex team. The most successful team is Yorkshire, whose county club was founded in 1863. They have won the title outright on 32 occasions, most recently in 2014 and 2015.

All the other Test countries have a similar setup. Australia's national championship involves the various state sides playing for the Sheffield Shield; in India, the championship is the Ranji Trophy; in South Africa, the CSA 4-Day Series; and so on. Women's national championships take place in a number of countries; for example, the one in England is a 50-over competition involving sixteen county teams.

Minor cricket

[change | change source]Below the national championship level in each country there are various leagues, often organised on a state, county or regional basis, that include clubs which are classed as minor although in many cases the playing standards are anything but minor. Again using England as an example, the main minor competition is the Minor Counties Championship which began in 1895, and involves 20 county teams that have not qualified for the County Championship, although it is possible for a minor county to achieve this qualification. The last to do so was Durham in 1992. The most successful minor counties team is Staffordshire, whose most famous player was the world-class bowler Sydney Barnes.

Below the minor counties level are numerous regional leagues which involve town and village clubs whose players are generally local residents. These tend to play at weekends only. Some of the leagues are notable for high standards, especially as professionals have frequently been employed. For example, the great Gary Sobers played for Radcliffe Cricket Club in the Central Lancashire League for several seasons around 1960. Other notable leagues in England are the Lancashire League and the Bradford League.

Schools cricket has always been very important for giving youngsters an introduction to the skills of the sport, and this has always been most effective where good quality coaching has been available.

Olympics

[change | change source]So far, the only time cricket has been played in the Olympic Games was in 1900 when just two teams, nominally Great Britain and France, took part. Neither was nationally representative but the "British" team won the only match staged. Subsequently, cricket showed no interest in the Olympics until the 2010s when the ICC began a dialogue with the International Olympic Committee.

Details are yet to be finalised but it has been announced that men's and women's Twenty20 competitions will form part of the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

Other types of cricket

[change | change source]In domestic competitions, limited-overs games of differing lengths are played. There are also numerous informal variations of the sport played throughout the world that include beach cricket, French cricket, Indoor cricket, Kwik cricket, and all sorts of card games and board games that have been inspired by cricket.

Notes

[change | change source]References

[change | change source]- ↑ Maun 2009, p. 148.

- ↑ Maun 2009, pp. 255–257.

- ↑ Altham 1962, p. 50.

- ↑ Altham 1962, pp. 35, 50–52.

- ↑ "The Laws of Cricket" (3rd ed.). Marylebone Cricket Club. 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ↑ "Narendra Modi Stadium". ICC. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- 1 2 "Law 19. Boundaries". Marylebone Cricket Club. 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ↑ Williams, John. "C. L. R. James". London Review Bookshop. Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ↑ "Law 6: The Pitch". Marylebone Cricket Club. 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ↑ "Laws 2.7/2.8. Fitness for play / Suspension of play". Marylebone Cricket Club. 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ↑ "Law 8. The Wickets". Marylebone Cricket Club. 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ↑ "Law 7. The Creases". Marylebone Cricket Club. 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ↑ "Law 2. The Umpires". MCC. 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ↑ "Law 3. The Scorers". MCC. 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ↑ "Law 5. The Bat". MCC. 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ↑ "Law 4. The Ball". MCC. 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2025.

- ↑ "Implements and Equipment". MCC. 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ↑ "Law 27. The Wicket-keeper". MCC. 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ↑ "Laws 28.1/28.3. The Fielder". MCC. 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- 1 2 "Law 13.4. The Toss". MCC. 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ↑ "Law 28.5. Fielders not to encroach on pitch". MCC. 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2025.

- ↑ "Law 24. Fielders absence; substitutes". MCC. 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2025.

- ↑ Bowen 1970, p. 282.

- 1 2 Bowen 1970, p. 140.

- ↑ Major 2007, p. 17.

- ↑ Underdown 2000, pp. 3–4.

Bibliography

[change | change source]- Altham, H. S. (1962). A History of Cricket, Volume 1 (to 1914). London: George Allen & Unwin. ASIN B0014QE7HQ.

- Bowen, Rowland (1970). Cricket: A History of its Growth and Development. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. ISBN 978-04-13278-60-9.

- Major, John (2007). More Than A Game. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-00-07183-64-7.

- Maun, Ian (2009). From Commons to Lord's, Volume One: 1700 to 1750. Cambridge: Roger Heavens. ISBN 978-19-00592-52-9.

- Underdown, David (2000). Start of Play. Westminster: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-07-13993-30-1.

Other websites

[change | change source]- What Is Cricket? Get to know the sport: a video produced by the International Cricket Council.

- "Cricket". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.