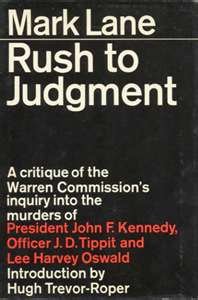

Rush to Judgment

Cover of first American edition | |

| Author | Mark Lane |

|---|---|

| Subject | Assassination of John F. Kennedy |

| Publisher | Holt, Rinehart & Winston |

Publication date | August 1966 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Pages | 478 pp. |

| OCLC | 4215197 |

| LC Class | E842.9 .L3 1966a |

Rush to Judgment: A Critique of the Warren Commission's Inquiry into the Murders of President John F. Kennedy, Officer J.D. Tippit and Lee Harvey Oswald is a 1966 book by American defense attorney Mark Lane. He examines the assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy—and the murders of Dallas policeman J.D. Tippit and accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald—and takes issue with the investigatory methods and conclusions of the Warren Commission.

Lane's book, along with Inquest by Edward Jay Epstein and The Oswald Affair by Léo Sauvage, was part of the initial wave of mass market hardcovers to challenge the Warren Commission's findings.[1][2][3] Rush to Judgment was a fixture on best seller lists for two years, first in hardcover, then in paperback.[4][5] According to Alex Raksin, the book's success "opened the floodgate" for JFK assassination conspiracy theories.[6]

Background

[edit]The genesis of Rush to Judgment began soon after JFK's assassination on November 22, 1963. Within weeks, Lane wrote a letter to Chief Justice Earl Warren, requesting that the Warren Commission give consideration to appointing a defense counsel to advocate for Lee Harvey Oswald's rights.[7] In the letter, Lane enclosed a 10,000 word "brief", which he also submitted for publication.[8][9] The only newspaper that would publish the brief was a small New York-based left-wing weekly, the National Guardian,[10] where it appeared on December 19, 1963, with the article title, "Oswald Innocent? A Lawyer's Brief".[11] Lane organized the article as a set of rebuttals against fifteen assertions by Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade regarding the JFK assassination and the murder of Dallas policeman J. D. Tippit.[12] The remainder of the article was a defense of Oswald who deserved, in Lane's estimation, "the presumption of innocence".[8]

By January 1964, Lane was serving as unpaid legal counsel for Oswald's mother Marguerite. After reading the National Guardian article, she asked him to represent her deceased son before the Warren Commission.[13] The next month, Lane started conducting his own witness interviews.[14] He was also speaking publicly about the assassination. In a series of lectures, many of them in New York City, he would talk for 2-3 hours about what he viewed as anomalies in the government's assassination narrative, i.e., that Oswald was the lone gunman.[15] When the Warren Report was published in September 1964, Lane was already expanding his article into a book.[16] He wrote most of Rush to Judgment while living in Europe.[17] He had a complete draft by early February 1965.[18] He returned to the U.S. and initiated a lengthy, frustrating search for a publisher:

These were the bitter and difficult months. I had but one copy of the manuscript, some of it typed, portions handwritten, and I was possessed of neither the time nor the funds to have other copies made. Each publisher required from one to three weeks to make a decision. A month might well be spent awaiting two rejections. It was necessary during this period to stand by so that I might be available to the publisher then considering the work should questions arise. There were many hopeful moments when it seemed that the document would at last be accepted. But each of these was followed by substantially longer periods of dejection.[19]

After being turned down by over a dozen U.S. publishers, including Grove Press, Simon & Schuster, Random House, and W. W. Norton, he "decided to try for a publisher in England."[20] He sent the manuscript to James Michie, editorial director of The Bodley Head, a British publishing house. Michie asked Hugh Trevor-Roper, Regius Professor of History at the University of Oxford, to evaluate the manuscript. Trevor-Roper strongly recommended it, advising "it would be a classic when published."[21] Lane signed a contract with Bodley Head in 1966, with an advance payment of £2,000.[22] He later noted sardonically: "And so it came to pass that this American story about the death of an American president found its first publisher in a foreign country."[21] Trevor-Roper would go on to write the book's Introduction. He is thanked by Lane in the Acknowledgments, along with Bertrand Russell[23] and Arnold Toynbee, for being "kind enough to read the manuscript and make suggestions".[24] Shortly after securing a British publisher, Lane found an American publisher in Holt, Rinehart and Winston, which brought out the book in August 1966.[25]

Years later, Lane recalled his process for choosing a suitable title for his work:

When I wrote the book...I was looking for a title that would have some historic resonance. I came upon the phrase I needed in a speech by Lord Chancellor Thomas Erskine, back when he was defending James Hadfield around 1800. Hadfield was charged, appropriately enough for my purposes, with the attempted assassination of George III. Erskine spoke these words in defense of Hadfield: "An attack upon the king is considered to be parricide against the state, and the jury and the witnesses, and even the judges, are the children. It is fit, on that account, that there should be a solemn pause before we rush to judgement."[26]

Some of Lane's advisers, such as Raymond Marcus and Deirdre Griswold of the Citizens Committee of Inquiry (CCI), argued that "Rush to Judgment" was a poor title choice because it would not be obvious to book buyers that the subject matter was the JFK assassination (they proposed instead, "The Assassination: Rush to Judgment").[18] Nonetheless, the book retained its original title, while adding the subtitle, "A Critique of the Warren Commission's Inquiry into the Murders of President John F. Kennedy, Officer J.D. Tippit and Lee Harvey Oswald".[18]

Book summary

[edit]Rush to Judgment is a detailed analysis of the 26 volumes of testimony and exhibits collected during the Warren Commission's ten-month-long investigation, and of the Warren Report—a separately published 888-page volume summarizing the Commission's findings. Given that Lane structured his book as a lawyer's point-by-point rebuttal of those combined 27 volumes, The Texas Observer called Rush to Judgment "one of the longest book reviews in history."[27] Lane divided his analysis into four parts:

Part One: Three Murders – This part makes up roughly half the book and focuses on the JFK murder. Lane raises numerous objections to the Commission's "Oswald-acted-alone" narrative. Among the chapter titles are "Where the Shots Came From", "The Magic Bullet", and "The Murder Weapon". Lane attempts to refute the Commission's conclusion that only three shots were fired, and they all came from the sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository. He cites multiple witnesses, some interviewed by the Commission and some only interviewed by Lane, who recounted seeing or hearing shots from the grassy knoll in Dealey Plaza. He also claims that none of the Commission's expert marksmen were able to duplicate Oswald's shooting feat (a claim which was later disputed[28]). Lane emphasizes that the Dallas police officers who found a rifle on the sixth floor identified it as a German Mauser bolt-action model, a discovery broadcast in a TV press conference.[29] But the next day, after the FBI reported that Oswald owned an Italian Mannlicher-Carcano rifle, Lane says the story changed and all subsequent claims were that a Mannlicher-Carcano was found on the sixth floor.[30]

In the latter chapters of Part One, Lane seeks to raise a reasonable doubt that Oswald murdered Dallas policeman J. D. Tippit less than 45 minutes after assassinating Kennedy. In the chapter titled "Forty-Three Minutes", Lane supplies a timeline of Oswald's post-assassination movements and whereabouts, and doubts whether he could have arrived quickly enough to the residential street where Tippit was gunned down.[31] In the next chapter, Lane quotes an eyewitness to the Tippit murder who saw two shooters, neither of whom looked like Oswald, but she was never called to testify.[32] Part One ends with the murder of Oswald on November 24.

Part Two: Jack Ruby – This part continues the examination of Oswald's murder, with a focus on his killer, Jack Ruby. The opening chapter, "How Ruby Got Into the Basement", reminds readers that the Commission admitted "it was unable to determine how Jack Ruby entered the well-guarded basement of the Police and Courts Building"[33] shortly before Oswald's transfer to another jail. Lane discusses Ruby's friendships within the Dallas Police Department, his alleged presence at the assassination site and at Parkland Hospital afterwards (which Ruby denied),[34] and how seemingly reluctant the Commission was to obtain Ruby's testimony. They waited six months before calling him to testify,[35] and the Commissioners "asked few questions, and almost every one of his disclosures was volunteered and was not in response to efforts made by the Commissioners or their staff."[36]

Part Three: The Oswalds – Lane describes Oswald's Soviet defector wife Marina, and his mother Marguerite. He objects to the manner in which both women were held in "protective custody" by the U.S. Secret Service and FBI, and barred from any access to reporters.[37] He contends that Marina's testimony was coached and/or coerced. Unlike Ruby, she was questioned extensively by the Commission, for four consecutive days, and was recalled again and again until the close of hearings in September.[38] Lane enumerates instances where she changed her statement to further implicate her late husband.[39] For example, on the day of the assassination, she examined the alleged murder weapon and said she could not identify it as belonging to her husband. But when she was shown the rifle again in February 1964, she said, "This is the fateful rifle of Lee Oswald."[40] She initially proclaimed Oswald's innocence, but then later declared "that her husband was the assassin". Lane writes, "The question that occurs is—what made Marina Oswald change her mind?"[41]

Part Four: The Commission and the Law – Lane attacks the Commission for lack of objectivity. He cites a passage from the Warren Report: "The Commission has functioned neither as a court presiding over an adversary proceeding nor as a prosecutor determined to prove a case, but as a factfinding agency committed to the ascertainment of the truth."[42] He then writes:

I believe that, on the contrary, the Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy is less a report than a brief for the prosecution. Oswald was the accused; the evidence against him was magnified, while that in his favor was depreciated, misrepresented or ignored. The proceedings of the Commission constituted not just a trial, but one in which the rights of the defendant were annulled.[43]

Lane ends Part Four by writing, "If the Commission covered itself with shame, it also reflected shame on the Federal Government.... As long as we rely for information upon men blinded by the fear of what they might see, the precedent of the Warren Commission Report will continue to imperil the life of the law and dishonor those who wrote it little more than those who praise it."[44]

The book's back matter contains an Appendices section which provides some of the reports, affidavits, testimony excerpts, etc., that are referenced in the four previous parts.

Reception

[edit]In her review in The Texas Observer, Frankie Randolph said Lane "demonstrates that a lawyer for the defense can make mincemeat of the government's case", and she added, "again and again he does what every thoughtful critic has done: he demands to know why the commission failed to so much as talk to so many witnesses and others whose testimony was of critical, pivotal importance."[27] In the "Book Week" section of The Washington Post, Norman Mailer praised Lane's analysis and argued that the JFK assassination demanded a more radical, democratic inquiry than the one carried out by the Warren Commission: "One would propose...[a] real commission—a literary commission supported by public subscription to spend a few years on the case.... I would trust a commission headed by Edmund Wilson before I trusted another by Earl Warren. Wouldn't you?"[45]

In The New York Review of Books, Fred Graham commended what he termed the "second round" of JFK assassination books (i.e., Rush to Judgment and The Oswald Affair) for being "based upon more research and reflection" than earlier books such as Joachim Joesten's Oswald: Assassin or Fall Guy? (1964), which Graham claimed had been "largely discredited".[46] But Graham faulted Lane, Epstein, Sauvage and other assassination critics for their failure to "get together on an alternative to the Warren Commission's conclusions."[46] TIME magazine made a similar argument in its rebuke of skeptics like Lane: "[F]or the time it took and the methods it used, the commission did an extraordinary job.... Although its conclusions are being assailed, they have not yet been successfully contradicted by anyone. Despite all the critics' agonizing hours of research, not one has produced a single significant bit of evidence to show that anyone but Lee Harvey Oswald was the killer, or that he was involved in any way in a conspiracy with anyone else."[47]

In The Atlantic magazine, Oscar Handlin called Rush to Judgment

a passionate denial of the Commission's conclusions that all the shots were fired from behind the President's car by a lone assassin. Lane's method is that of the crossexaminer who sets out to break down a prosecution case. The Warren Commission Report is indeed vulnerable. But the pyrotechnics of the courtroom do not always advance the knowledge of the truth. Lane frequently points to questions that the Commission did not ask. But he also, and less justifiably, scatters along the way innuendos that lack substantive support in the effort to implicate anti-Castro refugees or right-wing extremists.[48]

In the Stanford Law Review, John Kaplan denounced the book in a more fundamental way. He essentially accused Lane of using a lawyer's tricks to make a dishonest argument, which was a criticism that would be leveled by other Lane detractors:

[Rush to Judgment] is a wide-ranging attack on almost every conclusion of the Warren Commission, and it at least initially leaves the reader thinking that if only a tenth of Lane's implications are true, he has more than made his case that the Warren Commission's performance is a major national disgrace. The problem is that if the reader (as, of course, few readers do) begins to check the assertions in Rush to Judgment against the evidence, he will find again and again that he has been expertly gulled. Though the book is cleverly constructed to make more use of implication and innuendo than of fact, nowhere near one-tenth of what Lane says stands up to careful scrutiny.[49]

In a mixed review in The New York Times, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt concurred with Lane that

the commission skipped the fundamental question raised the moment shots rang out in Dallas, which was "What happened?" and leaped by questionable logic to subsidiary ones: Did Lee Harvey Oswald shoot the President and did he act alone? Then, operating from the premise that he did both, the commission proceeded to gather the evidence that supported this conclusion, even twisting it when it proved uncooperative, and ignored that which seemed downright contradictory.[50]

Lehmann-Haupt chided Lane for neglecting to mention evidence which ran counter to his narrative. The reviewer added, however, that "it is the very bias and shrillness of Rush to Judgment ... that comprises its effectiveness. For it presents Mark Lane as Lee Harvey Oswald's advocate, crying to be let in to defend his underdog and thereby join a not altogether disreputable tradition in American history."[50]

Rush to Judgment sold extremely well. Lane noted:

The book appeared on the best-seller lists published by the New York Times and Time magazine every week for more than six months. During a considerable period of the time it occupied the number one position on the list. Subsequently, when published in paperback by Fawcett Publications, it became the number one paperback best-seller and for a time appeared simultaneously on both the hardcover and paperback lists.[51]

Controversies

[edit]According to former KGB officer Vasili Mitrokhin in his 1999 book The Sword and the Shield, the KGB helped finance Lane's work on Rush to Judgment without the author's knowledge.[52] The KGB reportedly used journalist Genrikh Borovik as a contact and provided Lane with $2,000 for research and travel in 1964.[53][54] Max Holland repeated this allegation in a February 2006 article in The Nation titled "The JFK Lawyers' Conspiracy". Lane called the allegation "an outright lie" and wrote, "Neither the KGB nor any person or organization associated with it ever made any contribution to my work."[55]

In his final JFK assassination book, Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK (2011), Lane asserts that visits to prospective publishers by intelligence assets made it impossible for him to find a U.S. publisher; "only after a British publisher agreed to print it did an American company acquiesce."[56] He also relates how Benjamin Sonnenberg Jr., an American living in London, volunteered his services to Bodley Head as an editor of the Rush to Judgment manuscript. When Lane saw the suggested edits, he initially appreciated the stylistic improvements.[57] But he eventually noticed that some of Sonnenberg's changes were counterproductive, and even destructive, and so he asked him to withdraw from the project.[58] Lane says he discovered in 1991, with the publication of Sonnenberg's Lost Property: Memoirs and Confessions of a Bad Boy, that Sonnenberg admitted being "a CIA agent who was relaying information to the Agency about what was in the book",[12] and was altering its contents to protect the Agency.[59]

Documentary

[edit]| Rush to Judgment | |

|---|---|

| Directed by | Emile de Antonio |

| Narrated by | Mark Lane |

| Distributed by | Impact Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 122 minutes |

| Country | United States |

In 1967, the documentary film Rush to Judgment was released.[60] Based on Lane's book, it was directed by Emile de Antonio and hosted by Lane.[61][62] Assassination witnesses who present their observations on-camera include Lee Bowers, Charles Brehm, Acquilla Clemons, Napoleon Daniels, Patrick Dean, Nelson Delgado, Richard Dodd, Nancy Hamilton, Sam Holland, Joseph Johnson, Penn Jones Jr., Roy Jones, Jim Leavelle, Mary Moorman, Orville Nix, Jessie Price, James Simmons, James Tague, and Harold Williams.[63]

Paul McCartney was an early enthusiast of the Rush to Judgment book. He met Lane in London in 1966. When the Beatle learned that a documentary was being made, he volunteered to compose a film score. In his memoir, Lane writes, "I was astonished by that generous offer and speechless for a moment. I thanked him, but then I cautioned him that the subject matter was very controversial in the United States and that he might be jeopardizing his future."[64] McCartney was not dissuaded, but no score was included in the film, on the recommendation of de Antonio (whom Lane refers to as 'D'):

I argued with D about the musical score to no avail. He insisted that a score by Paul McCartney would not increase the film's popularity or reach, and would prevent it from being "stark and didactic", a phrase that I still did not comprehend and one D could never adequately explain. The film without a musical score was stark enough and was moderately successful.[65]

The film debuted on the BBC in 1967.[65] A remastered version was posted on YouTube in 2024.[66]

Legacy

[edit]In a study of changing public reaction to the government's assassination inquiry, Adam Fry wrote: "As the first major critic of the Warren Commission, Mark Lane's investigation marked a significant 'sea change' among the belief systems of the public.... Gallup polling data demonstrated a correlation between the publication of Rush to Judgment and the increasing belief that more than one person was involved".[67] In the immediate aftermath of November 1963, roughly 50% of Americans were skeptical of the "lone gunman" explanation. Following Lane's 1966 bestseller, the percentage steadily climbed to 81% by the mid-1970s.[68]

The rising public skepticism contributed to Congress voting in 1976 to create a House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA),[67] which was established through legislation that Lane helped draft.[4] In 1979, at the time of HSCA's final report, Tracy Kidder wrote about Rush to Judgment:

Today it seems a one-sided, largely outdated discussion of the evidence. What remains alive in it is Lane's voice, which is by turns reasonable (he admits that there was some small amount of unconvincing evidence against Oswald), sarcastic (he pretends to admire the commission's ingenuity in inventing evidence against Oswald), and oratorical (he holds that the commission has threatened to bring on nothing less than the downfall of the rule of law).[13]

Lane also influenced the nomenclature used to discuss the JFK assassination. For example, his ridicule of the Warren Commission's single-bullet theory–which he coined "The Magic Bullet" in Rush to Judgment[69]—became part of the lexicon,[4] as did his repeated use of the phrase "grassy knoll" (which he attributed to eyewitness Jean Hill, whom he interviewed in February 1964[14]).

A 2019 research report from the University of South Carolina described Lane's book as

one of the earliest and most effective critiques of the Warren Commission ... [that] centered around the perceived improbability of Oswald acting alone.... Critics of the book saw it as wildly speculative, biased, and indiscriminate. While its subject matter was disputed, Rush to Judgment was successful in starting a dialogue about the assassination and presenting new possible narratives to the American public.[70]

See also

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Lane, Mark (1966). Rush to Judgment: A Critique of the Warren Commission's Inquiry into the Murders of President John F. Kennedy, Officer J. D. Tippit and Lee Harvey Oswald. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. LCCN 66023886.

- Lane, Mark (1969) [1968]. A Citizen's Dissent: Mark Lane Replies. Fawcett Crest. p. 49. LCCN 68013044.

- Kelin, John (2007). Praise from a Future Generation: The Assassination of John F. Kennedy and the First Generation Critics of the Warren Report. San Antonio, Texas: Wings Press. ISBN 978-0916727321.

- Lane, Mark (2011). Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1616084288.

- Lane, Mark (2012). Citizen Lane: Defending Our Rights in the Courts, the Capitol, and the Streets. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN 978-1613740019.

References

[edit]- ^ Prior to Rush to Judgment, there had been a few self-published and small press books, by Harold Weisberg, Joachim Joesten, Sylvan Fox, Penn Jones Jr., Thomas G. Buchanan, etc., which questioned the Warren Commission's "lone gunman" theory.

- ^ Giglio, James N. (April 1992). "Oliver Stone's JFK in Historical Perspective". American Historical Association. Archived from the original on May 16, 2010.

- ^ Hoover, Bob (November 2, 2013). "The Next Page: The JFK assassination conspiracy circus". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

The first mass-market hardcover to confront the Warren Commission report was Rush to Judgment by Mark Lane, a lawyer active in liberal causes and onetime New York legislator. The 1966 work dissected the Warren findings with the authority of an experienced trial lawyer and the air of a legal brief for Oswald's defense.

- ^ a b c Schneider, Keith (May 12, 2016). "Mark Lane, Early Kennedy Assassination Conspiracy Theorist, Dies at 89". The New York Times.

- ^ Bratich, Jack Z. (2008). Conspiracy Panics: Political Rationality and Popular Culture. State University of New York Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0791473337.

- ^ Raksin, Alex (December 29, 1991). "Nonfiction". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ Kelin 2007, p. 15.

- ^ a b "Lawyer Urges Defense for Oswald at Inquiry". The New York Times. December 19, 1963. p. 24.

- ^ "Exhibits 1976 to 2189". Hearings Before the President's Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Vol. XXIV. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1964. pp. 444–445.

- ^ Carlson, Michael (May 17, 2016). "Mark Lane obituary". The Guardian.

- ^ Lane, Mark (December 19, 1963). "Oswald Innocent? A Lawyer's Brief". National Guardian.

- ^ a b DiEugenio, James (June 11, 2016). "Mark Lane, Part II: Citizen Lane". Kennedys and King.

- ^ a b Kidder, Tracy (March 1979). "Washington: The Assassination Tangle". The Atlantic.

- ^ a b Lane 2011, p. 14.

- ^ Kelin 2007, pp. 158–160.

- ^ Lane 1969, p. 43: Lane traces his decision to write the book to a conversation he had with Oscar Collier, a literary agent, not long after a televised debate between Marguerite Oswald and Melvin Belli. The debate occurred on The New Les Crane Show on August 5, 1964.

- ^ Lane 1969, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c Kelin 2007, p. 309.

- ^ Lane 1969, p. 51.

- ^ Lane 1969, p. 52.

- ^ a b Lane 2012, p. 161.

- ^ Lane 1969, p. 53.

- ^ Griffin, Nicholas, ed. (2001). The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell, Volume 2: The Public Years 1914-1970. Routledge. p. 576. ISBN 978-0415260121. In June 1964, Bertrand Russell raised public awareness about Lane's work by establishing a "Who Killed Kennedy committee" in England "for the purpose of making known the material he [Lane] has uncovered and his further findings."

- ^ Lane 1966, p. 25.

- ^ Lane 1969, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Safire, William (February 26, 1995). "On Language: Simpsoniana". The New York Times. Lane quickly added, "The British spelling of judgement, of course, has an extra e in it."

- ^ a b Randolph, Frankie (November 11, 1966). "November 22, 1963: The Case Is Not Closed" (PDF). The Texas Observer. A review of ten early JFK assassination books, including Rush to Judgment, Inquest, The Oswald Affair, and Forgive My Grief.

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent (2007). Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. W. W. Norton. p. 1005. ISBN 978-0393045253.

- ^ Lane 1966, pp. 409–410. In Appendix VI, Lane shows a photocopy of Dallas Constable Seymour Weitzman's sworn affidavit that he found a 7.65 caliber German Mauser rifle on the sixth floor.

- ^ Lane 1966, pp. 114–116.

- ^ Lane 1966, pp. 171–175.

- ^ Lane 1966, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Lane 1966, p. 219.

- ^ Keeffe, Arthur John (December 1966). "Reviewed Work: Rush to Judgment by Mark Lane". American Bar Association Journal. 52 (12): 1149–1151. JSTOR 25723860.

- ^ Lane 1966, p. 241.

- ^ Lane 1966, p. 242.

- ^ Lane 1966, pp. 243, 317, 320.

- ^ Lane 1966, p. 307.

- ^ Lane 1966, p. 323: "I believe it is fair to conclude that Marina Oswald was held incommunicado for reasons other than her security. Eventually she succumbed—she adopted the viewpoint of the [FBI] agents regarding the charges against her deceased husband."

- ^ Lane 1966, pp. 309–310.

- ^ Lane 1966, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Warren Commission Report, p. xiv

- ^ Lane 1966, p. 378.

- ^ Lane 1966, p. 398.

- ^ Mailer, Norman (August 28, 1966). "The Great American Mystery: A New Dissent on the Methods and Findings of the Warren Commission". The Washington Post. Book Week. pp. 1, 11–13.

- ^ a b Graham, Fred (August 28, 1966). "Round Two". The New York Review of Books.

- ^ "Essay: Autopsy on the Warren Commission". TIME. September 16, 1966.

- ^ Handlin, Oscar (October 1966). "Reader's Choice". The Atlantic.

- ^ Kaplan, John (May 1967). "Review: The Assassins". Stanford Law Review. 19 (5): 1110–1151. JSTOR 1227605.

- ^ a b Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (August 16, 1966). "Books of the Times: Rush to the Warren Committee Report". The New York Times.

- ^ Lane 1969, p. 55n.

- ^ Persico, Joseph E. (October 31, 1999). "Secrets From the Lubyanka: A historian examines an archive of Soviet files smuggled to the West by a former K.G.B. agent". The New York Times. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ Bugliosi 2007, p. 162.

- ^ Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, Basic Books, 1999. Excerpted here. According to the book, Soviet journalists, including KGB agent Genrikh Borovik, met with Mark Lane to encourage him in his research.

- ^ Holland, Max; Lane, Mark (March 2, 2006). "November 22, 1963: You Are There". The Nation. Contains Mark Lane's letter to The Nation in response to Max Holland's article, "The JFK Lawyers' Conspiracy", which appeared in the February 20, 2006 issue.

- ^ Lane 2011, p. 76.

- ^ Lane 1969, p. 55.

- ^ Lane 2011, p. 165.

- ^ Lane 2011, pp. 76–77.

- ^ "Rush to Judgment – Film Details". TCM.

- ^ "Rush to Judgment". IMDb. Retrieved November 4, 2025.

- ^ Wilonsky, Robert (April 21, 2011). "From the Film Vaults: Rush to Judgment". Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011.

- ^ "Rush to Judgment (1967)". Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Retrieved November 12, 2025.

- ^ Lane 2012, p. 175.

- ^ a b Lane 2012, p. 176.

- ^ "Rush to Judgment". YouTube. August 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Fry, Adam T. (April 15, 2020). The Public's Reaction, Over Time, to the Findings of the Warren Report (Thesis). University of Missouri–St. Louis.

- ^ Swift, Art (November 15, 2013). "Majority in U.S. Still Believe JFK Killed in a Conspiracy". Gallup.

- ^ Lane 2011, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Fox, Will (2019). "Doubt and Deception: Public Opinion of the Warren Report". University of South Carolina – Office of the Vice President for Research.

External links

[edit]- 1967 films

- 1966 non-fiction books

- 1960s American films

- American documentary films

- Documentary films about the assassination of John F. Kennedy

- Films directed by Emile de Antonio

- Holt, Rinehart and Winston books

- John F. Kennedy assassination conspiracy theories

- Non-fiction books about the assassination of John F. Kennedy

- The Bodley Head books