Prilep

Prilep

Прилеп (Macedonian) | |

|---|---|

From top, clockwise: panorama of Prilep from Hotel Kristal Palas; Čento Square; Čarši Mosque ruins; Mound of the Unbeaten; Memorial Museum of October 11, 1941; Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius; commercial building in city centre | |

| Nickname: "The city under Marko's Towers" | |

| Coordinates: 41°20′40″N 21°33′10″E / 41.34444°N 21.55278°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| Municipality | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Borce Jovceski[1][2] |

| Area | |

• Town | 1,194.44 km2 (461.18 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 19.29 km2 (7.45 sq mi) |

| Elevation | +620 m (2,030 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

• Town | 63,308 |

| • Density | 64.27/km2 (166.5/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 63,308 |

| • Urban density | 3,282/km2 (8,500/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 79,834 |

| Demonym | Prilepian (Macedonian: Прилепчанец / Prilepchanec |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| Postal codes | 7500 |

| Area code | (+389) 048 |

| Vehicle registration | PP |

| Climate | Cfa |

| Website | www |

Prilep (Macedonian: Прилеп [ˈpriːlɛp] ⓘ) is the fourth-largest city in North Macedonia.[3] According to 2021 census, it had a population of 63,308.

Name

[edit]

The name of Prilep appeared first as Πρίλαπος in Greek (Prilapos)[nb 1] in 1014 as the place where Samuel of Bulgaria had died after the Battle of Kleidion. The town was attached literally to the rocky hilltop above, and its name derives from Old Slavic, and means “stuck on the rock” [5] (pri- + lep = on + stuck).

In other languages it is:

- Greek: Prilapos, Πρίλαπος

- Albanian: Përlep or Përlepi, or Prilep or Prilepi

- Bulgarian and Serbo-Croatian: Прилеп / Prilep

- Latin: Prilapum

- Aromanian: Pãrleap[6]

- Turkish: Pirlepe, or Perlepe

Economy

[edit]Prilep is a centre for high-quality tobacco and cigarettes, as well as metal processing, electronics, timber, textiles, and food industries. The city also produces a large quantity of Macedonian Bianco Sivec (pure white marble).

Tobacco is one of Prilep's traditional cash crops and prospers in the Macedonian climate. Many of the world's largest cigarette makers, such as Marlboro, West and Camel use Prilep's tobacco in their cigarettes after it is processed in local factories such as Tutunski kombinat Prilep. A Tobacco Institute is established in the city in order to produce new types of tobacco and it was the first example of applying genetics to agriculture in the Balkans.[citation needed]

Vitaminka is a company located in Prilep specializing in food processing. It is one of the largest food processing companies in North Macedonia.[7]

A Gentherm production plant is located in Prilep.

History

[edit]

In antiquity, the region of Prilep was part of ancient Pelagonia that was inhabited by the Pelagones, an ancient Greek tribe of Upper Macedonia, who according to Strabo,[8] were Epirote Molossians.[9] The region was annexed to the Macedonian kingdom during the 4th century BC. In September 2007 archeological excavations in Bonče, revealed a tomb of what is believed to be the burial site of a Macedonian ruler dating 4th century BC.[10] Near Prilep, close to the village of Čepigovo, are the ruins of the ancient Macedonian city of Styberra (Ancient Greek: Στύβερρα), first a town in Macedonia and later incorporated into the Roman Empire.[11][12] Styberra, though razed by the Goths in 268, remained partly inhabited.

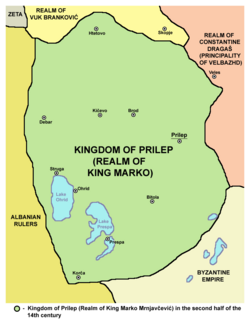

The town was first mentioned in Greek as Πρίλαπον (Prilapon) in 1014, as the place where Bulgarian Tsar Samuil allegedly had a heart attack upon seeing thousands of his soldiers had been blinded by the Byzantines after the Battle of Kleidion. Byzantium lost it to the Second Bulgarian Empire, but later retook it. Prilep was acquired in 1334 by Serbian King Dušan and after 1365 the town belonged to King Vukašin, co-ruler of Dušan's son, Tzar Stefan Uroš V. After the death of Vukašin in 1371, Prilep was ruled by his son Marko.[13] In 1395 it was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire, of which it remained a part of until 1913, when it was annexed by the Kingdom of Serbia.

During the Ottoman period, besides the ethnic Turks and the majority Slavic population, Prilep was also home to both a Sunni Muslim and Orthodox Christian Albanian community, which lived alongside. Serbian historiographer Jovan Hadži-Vasiljević wrote:[14]

- "Between Turks and Muslim Albanians who have lived in the city (Prilep), it is very difficult to distinguish, especially between the old families of the city. The Mohammedan Albanian families, as soon as they arrived in the city, merged with the Turks, just as the Christian Albanian families merged with the Slavs or the Greeks"

Bulgarian researcher, Georgi Traychev, wrote:[15]

- "In the city of Prilep, there were no pure Greeks, but there are several (dozens) of Grecomans supported by schismatic Vlachs and Albanian Christians."

The newspaper Прилеп преди 100 години ("Prilep 100 years ago". Sofia, 1938) puts forward data about the presence of Orthodox Albanians in Prilep. There it is emphasized that after their arrival in the city around the 18th-19th century, the Christian Vlach and Albanian elements have assimilated under the influence of Bulgarian population, and that there are no longer any traces of them. Information is also given for Albanians of both denominations. It is emphasized that in total there are 2412 Muslim Albanian residents in the city. Of the Orthodox Albanians, a part has been Bulgarianized, while others have been Hellenised. In the newspaper there is also a report about the Orthodox Albanian entitled Ico Kishari, whose family, along with the Tilevci, Georgimajkovci and Ladcovci, were Orthodox Albanian refugees from Moscopole who had settled in the beginning of the 19th century. The newspaper also describes a great Albanian religious man, who has spent his whole life as a churchgoer. Out of respect for his work, the church granted him a pension.[16]

The main struggle in the late 19th century was between the Bulgarian Exarchate and the Greek Patriarchate. Following the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870, as a result of plebiscites held between 1872 and 1875, the Slavic population in the bishoprics of Skopje and Ohrid voted overwhelmingly in favor of joining the new Bulgarian national Church (Sanjak of Üsküp - 91%, Sanjak of Ohrid - 97%).[17] In the plebiscite of 1873 the inhabitants of the town voted en masse to join the Bulgarian Exarchate.[18] In this way the Slavic population in the town became "Bulgarian Exarchists."[19] Over 97% of the citizens in the Prilep region per 1881-82 Ottoman Census, were listed as adherents of the Bulgarian Church.[20] According to the IMRO revolutionary Hristo Shaldev, who was also the director of Bulgarian schools in Prilep, the town was a major center of the Bulgarian national revival in Western Macedonia in the 19th century.[21]

Per Yugoslav and Macedonian sources in the late 19th century, the Macedonian Orthodox community in Prilep began resisting the Greek and early Bulgarian pressures. The Macedonian Orthodox community rejected the authority of the Patriarchate of Constantinople and sought an independent Church. They replaced Greek with Macedonian in religious services and education, preparing textbooks in their native language. During this push for national identity, Bulgarian intellectuals tried to impose the Bulgarian language, especially after the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870 and the Bulgarian Principality in 1878. The celebration of Vidovdan in Prilep was prohibited by the Bulgarian church.[22] Despite pressure, Prilep resisted Bulgarian control, maintaining its own school and religious practices. According to official letter from Dimitrije Bodi, the Serbian consul in Bitola, to the Serbian minister of exterior at that time, the people that were dissatisfied with the Exarchate formed a strong anti-Exarchate movement reaching 1,200 households.[23] The locals, led by priest Spase Igumenov, petitioned Sultan Abdul Hamid II, declaring their desire for a Macedonian national school and rejecting Bulgarian ecclesiastical authority, while affirming their Orthodox faith under papal protection. The petition was signed in 1887 by 25 prominent people from Prilep.[24][25]In their letter to the Sultan, they wrote:[26][27]

- "We, the undersigned from the city of Prilep, subjects of His Imperial Majesty, the august Sultan Abdul Hamid II, wish to have a national Macedonian school. And since we are not Bulgarians, we do not recognize the Bulgarian Ecclesiastical Community nor its schools. For religious protection, we recognize the Pope, but without changing the dogmas of the Orthodox Church."

In 1891, the initiator of the action, Spas Igumenov, who was former head of the Bulgarian Exarchist community in Prilep, published in the Constantinople newspaper of the Bulgarian Exarchate "Novini" a refutation in response to accusations that he was an accomplice and perpetrator of Uniate and Serbian propaganda, stating "With pride I confess my Bulgarian nationality and recognize the spiritual authority of the Holy Bulgarian Exarchate in Constantinople."[28] By the end of 1893, the Bulgarian Exarchate took over nearly all of the villages in the Prilep area.[29] According to the statistics of the secretary of the Bulgarian Exarchate, Dimitar Mishev ("La Macédoine et sa Population Chrétienne") in 1905, the Christian population of Prilep consisted of 17,085 Bulgarian Exarchists, 240 Slavic Patriarchists (Serbomans and Grecomans), 50 Greeks and 420 Vlachs.[30]

Prilep's bazaar began to develop in the 18th century. One of the largest annual fairs in Macedonia was held in Prilep in the middle of the 19th century. European consulate exhibitions of 1887 estimate the population of Prilep to approximately 6.500 individuals, of which 4.000 were Bulgarians, 2.000 were Turks and the rest were Serbs with Greeks and Aromanians.[31] During the Great Eastern Crisis, the local Bulgarian movement of the day was defeated when armed Bulgarian groups were repelled by the League of Prizren, an Albanian organisation opposing Bulgarian geopolitical aims in areas like Prilep that contained an Albanian population.[32]

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Prilep was part of the Manastir Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire. It was occupied by Bulgaria between 17 November 1915 and 25 September 1918 during World War I. In 1918 Prilep became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and from 1929 to 1941 it was part of the Vardar Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. On 8 April 1941, just two days after the start of the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia, Prilep was occupied by the German Army, and on 26 April 1941 by the Bulgarian Army. Together with most of Vardar Macedonia, Prilep was annexed by the Kingdom of Bulgaria from 1941 to 1944. After 9 September coup d'etat the commander of the Bulgarian garrison, refused to withdraw and remained in the city with the Yugoslav guerrillas, managing to hold it for 10 days, blocking the movement of the German troops.[33] Afterwards the German Army retook the town. Prilep was definitively taken by communist partisans on 3 November 1944. From 1944 to 1991 the town belonged to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, as part of its constituent Socialist Republic of Macedonia. Since 1991 the town has been part of the Republic of North Macedonia.

Culture

[edit]

- One of the most important institutions in the city is the Institute of Old Slavic Culture.

- An art colony is hosted in the center of Prilep in the Center of Contemporary Visual Arts. The colony was founded in 1957 by the archaeologist Prof. Boshko Babikj, but organized by the initiative of Prof. Babikj and the academic painter Prof. Risto Lozanovski, making it perhaps one of the oldest colonies in southeastern Europe and the oldest one on the Balkans, for sure. It hosts painters and sculptors (working in marble, metal and wood) every year and, periodically, it hosts workshops and symposia for vitrage (glass design), mosaics, photography, graphics and clay, from countries around the world. The collection of sculptures carved in wood was acknowledged as a cultural heritage by the most relevant criticizers and opinion makers. 2007 was the 50th anniversary of the colony.

- Every year in October the International Children's Music Festival "Asterisks" brings together children from all over the world.

- Every year the Professional Theatre Festival of Macedonia, honouring Vojdan Chernodrinski, who was born in village Selci near Struga and Debar.

- The Monastery of Zrze and the Monastery of the Holy Archangel Michael which has 12th and 14th-century frescoes are notable sites of the culture of Prilep.

- Pivofest (Beer fest) is an annual four-day party held in the middle of July that attracts around 200,000 visitors to the city. There are international popular music acts performing nightly on the main stage in the square as well as at the various clubs around town. Pivofest features a growing number of foreign and domestic beers as well as an opportunity for Prilep to showcase its famous barbecue considered the best in North Macedonia.

- Pročka is a centuries-old religious holiday of forgiveness and celebration that in 2001 found an organized manifestation as "Prilep Carnival" and has been a member of the Federation of European Carnival Cities since 2006. Despite the new official name, the festival is still known as Pročka by the locals and is called Pročka in the official tourist guide. The highlight of the festival is the mask parade which runs through the centre of the town and hosts participants from multiple European countries. There is a prize given for the best costume and many of the costumes are elaborate. There are also concerts, parties, and much traditional food during the festival which is held in February.

Language

[edit]The dialect of Prilep, forms the basis for the Standard Macedonian. When the Socialist Republic of Macedonia was formed as part of Yugoslavia at the end of the WWII, the Macedonian language was recognized as distinct one. Then the dialects of Prilep, Veles, Bitola and Ohrid were chosen as the basis for the new official language, because of their central position in the region of Macedonia.

Art and Architecture

[edit]

The main square in Prilep is called "Alexandria", in honor of Alexander the Great. The reconstruction of the square began in 2005 and it was completed in 2006. The reconstruction cost 700.000 Euros and its investor was the city of Prilep. During the reconstruction the monument of Alexander the Great was erected, among the other things.[34]

Several ancient sites grace Prilep including one at Markovi Kuli, St. Nicola's church from the 13th century, St. Uspenie church in Bogorodica, St. Preobrazenie church and the Tomb of the Unconquered, and a memorial in honour of the victims of fascism located in Prilep's central park. A large Roman necropolis is known there and parts of numerous walls have been found; the settlement was probably the ancient Ceramiae[35] mentioned in the Peutinger Table.[36] Roman remains can also be found near the Varoš monastery, built on the steep slopes of the hill, which was later inhabited by a medieval community. Many early Roman funeral monuments, some with sculpted reliefs of the deceased or of the Thracian Rider and other inscribed monuments of an official nature, are in the courtyard of the church below the southern slope of Varoš. Some of the larger of those monuments were built into the walls of the church.

The most important ancient monument is the old city of Styberra situated on Bedem hill near Čepigovo, in the central region of Pelagonia. As early as the time of the Roman–Macedonian wars, this city was known as a base from which the Macedonian king Perseus of Macedon set out to conquer the Penestian cities. An important site in the area is Bela Crkva, 6 km (4 mi) west of Styberra, where the town of Alkomenai was probably located. It was a stronghold of the Macedonian kings after it was rebuilt in the early Roman period and was at the Pelagonian entrance to a pass leading to Illyria. Part of the city wall, a gate, and a few buildings of the Roman period were uncovered here in excavations. All recent finds from these sites are in the Museum of the City of Prilep.

The Treskavec monastery, built in the 12th century in the mountains about 10 km (6 mi) north of Prilep under Zlatovrv peak, at the edge of a small upland plain 1100 meters above sea level. Prilep has frescoes from the 14th and 15th centuries and is probably the site of the early Roman town of Kolobaise. The name of the early town is recorded on a long inscription on stone which deals with a local cult of Ephesian Artemis.[37] The inscription was reused as a base for a cross on top of one of the church domes. Other inscriptions at Treskavec include several 1st century Roman dedications to Apollo. The old fortress was used by the Romans, and later the Byzantines. After all, even Tsar Samuil came here after the defeat at Belasica in 1014. During the Middle Ages, after 1371, Prince Marko rebuilt the citadel extensively, making it an important military stronghold.

Geography

[edit]Prilep covers 1,675 km2 (647 sq mi) and is located in the northern Pelagonia plain, in the southern part of North Macedonia. Prilep is the seat of the Prilep municipality and access is gained via the A3. It is 74 km (46 mi) (as the crow flies) from the capital Skopje, 44 km (27 mi) from Bitola, and 32 km (20 mi) from Kruševo.

Demographics

[edit]As of the 2021 census, Prilep had 63,308 residents with the following ethnic composition:

- Macedonians: 54,028

- Turks: 82

- Persons for whom data are taken from administrative sources: 4,692

- Serbs: 107

- Romani: 3,966

- Albanians: 106

- Vlachs: 30

- Others: 3

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Prilep | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

22.2 (72.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

18.2 (64.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.3 (45.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.2 (73.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

12.7 (54.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.5 (27.5) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

7.1 (44.9) |

| Source: Weatheronline[38] | |||||||||||||

Sports

[edit]Prilep is the home of several sports teams, the best known are:

- ФК Победа 2000-2009

- ФК 11ти Октомври 1999-2011

- ФК Корзо

- ФУДБАЛСКА ЕКИПА ЗА ГЛУВИ ОД ПРИЛЕП

- Ракометен Клуб „ПОБЕДА“

- Ракометен Клуб „МЕТАЛОТЕХНИКА“

- Ракометен Клуб „ПЕГАЗ“

- Ракометен Клуб „ТУТУНСКИ КОМБИНАТ“ – МЛАДИНЦИ

- Женски Ракометен Клуб „ТУТУНСКИ КОМБИНАТ“

- Женски Ракометен Клуб „Прилеп“

- Женски Ракометен Клуб „ТУТУНСКИ КОМБИНАТ“ – МЛАДИНЦИКИ

- Ракометен Клуб „ПАРТИЗАН“

- СПОРТСКА САЛА „МАКЕДОНИЈА“

- УНИВЕРЗАЛНА СПОРТСКА САЛА

- ПЛАНИНАРСКИ ДОМ „ДЕРВЕН“

Notable people

[edit]

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Prilep Municipality is twinned with:[39]

Asenovgrad, Bulgaria

Asenovgrad, Bulgaria Chernihiv, Ukraine

Chernihiv, Ukraine Garfield, United States

Garfield, United States Tire, Turkey

Tire, Turkey Topoľčany, Slovakia

Topoľčany, Slovakia Vincent, Australia

Vincent, Australia

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Mayor | Prilep". Municipality of Prilep. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ "Градоначалник" [Mayor] (in Macedonian). Municipality of Prilep. Retrieved 17 May 2025.

- ^ "Prilep Map - Western Macedonia". Mapcarta.com. 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ Scylitzes, Ioannes. "Σύνοψις Ἱστοριῶν" [Synopsis of Histories] (in Greek). Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ Mihajlovski, Robert. (2011). The Medieval Town of Prilep, p. 217. In: Basileia, Essays on Imperium and Culture in Honour of E.M. and M.J. Jeffreys, Editors: Geoffrey Nathan and Lynda Garland, Brill, ISBN 9004344896, pp. 217-230.

- ^ The War of Numbers and its First Victim: The Aromanians in Macedonia (End of 19th – Beginning of 20th century)

- ^ Askovic, Marija (25 March 2022). "Vitaminka". WB6 CIF. Retrieved 14 July 2025.

- ^ Strabo 9.5: For in consequence of the renown and ascendency of the Thessalians and Macedonians, those Epeirote, who bordered nearest upon them, became, some voluntarily, others by force, incorporated among the Macedonians and Thessalians. In this manner the Athamanes, Aethices, and Talares were joined to the Thessalians, and the Orestae, Pelagones, and Elimiotae to the Macedonians.

- ^ John Boardman and N. G. L. Hammond. The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 3, Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982, p. 284. A J Toynbee. Some Problems of Greek History, Pp 80; 99-103

- ^ Visoka and Staro Bonche: Center of the Kingdom of Pelagonia and the Royal Tomb of Pavla Chuka, Viktor Lilchikj Adams and Antonio Jakimovski

- ^ Richard Talbert, ed. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press. p. 49, and directory notes accompanying. ISBN 978-0-691-03169-9.

- ^ Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- ^ John Van Antwerp Fine (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4. pp. 288, 380–2.

- ^ Mustafa Ibrahimi. "SHQIPTARËT ORTODOKSË NË MAQEDONINË E VERIUT DHE DISA SHKRIME TË TYRE ME ALFABET CIRILIK". Gjurmime Albanologjike - Seria e shkencave filologjike 50:139-152."

- ^ Mustafa Ibrahimi. "SHQIPTARËT ORTODOKSË NË MAQEDONINË E VERIUT DHE DISA SHKRIME TË TYRE ME ALFABET CIRILIK". Gjurmime Albanologjike - Seria e shkencave filologjike 50:139-152."

- ^ Mustafa Ibrahimi. "SHQIPTARËT ORTODOKSË NË MAQEDONINË E VERIUT DHE DISA SHKRIME TË TYRE ME ALFABET CIRILIK". Gjurmime Albanologjike - Seria e shkencave filologjike 50:139-152."

- ^ The Politics of Terror: The Macеdonian Liberation Movements, 1893–1903, Duncan M. Perry, Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0822308134, p. 15.

- ^ Zahova, Sofiya, and Risto Blomster. “Roma Writings. Romani Literature and Press in Central, South-Eastern and Eastern Europe from the 19th Century until World War II.,” 2021, p. 27. doi:10.30965/9783657705207_002.

- ^ Nadine Lange-Akhund (1998) The Macedonian Question, 1893-1908, from Western Sources, East European Monographs, ISBN 9780880333832, p. 9.

- ^ Karpat, K.H. (1985). Ottoman population, 1830-1914: demographic and social characteristics. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Pres. p. 134-135, 140-141, 144-145.

- ^ Шалдев, Христо. Град Прилеп в Българското възраждане (1838 – 1878 год.), София, 1916, с. 4-70.

- ^ Протоколи од заседанијата на Прилепската општина, 1872-1886. Skopje: Institute for National History. 1956. p. 76.

- ^ Vukašin D. Dedović (2016). Rad Srbije na zaštiti srpskih državnih i nacionalnih interesa u Makedoniji od 1885. do 1912. godine. Istorijski Arhiv Kraljevo, 2021. p. 281.

- ^ Svetozarevikj, Branislav (2021). Македонци - милениумски сведошва за идентитетското име: (извори и анализи). p. 330.

...следат 25 потписи на угледни прилепчани.

- ^ Minovski, Mihajlo (1983). ДВА ДОКУМЕНТА ЗА АКЦИЈАТА НА ПРИЛЕПЧАНИ ОД 1887 ГОДИНА ЗА МАКЕДОНСКОГО НАРОДНО УЧИЛИШТЕ И САМОСТОЈНА ЦРКВА. p. 327.

- ^ Balcanica. Belgrade: Institute for Balkan Studies - Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 1982. p. 106.

"Nel 1867 la comunita macedone ortodossa di Prilep aveva informate le autorità turche di non riconoscere più la imposta giurisdizione del Patriarcato di Costantinopoli e di volere la loro Chiesa autocefala. Dalla locale scuola , dipendente dalla Chiesa e dalla liturgia ecclesiastica fu estromesso l'uso della lingua greca e reintrodotta la lingua macedone. Per l'uso scolastico furono preparati i testi in lingua macedone . Autori. Mentre era in atto a Prilep questa lotta per l'affermazione nazionale macedone, nella Chiesa e nella scuola locale, si intensificava l'azione degli intellettuali bulgari per imporre, alla gente di Prilep, l'uso della lingua bulgara. La loro azione si rafforzava dopo la formazione dell'Esarcato bulgaro del 28 febbraio 1870 e del Principato bulgaro nel 1878. L'Esarcato, grazie all'appoggio della diplomazia russa a Costantinopoli aveva ottenuto il permesso dal Sultano di nominare nella Macedonia diversi vescovi bulgari . Anche le scuole passavano sotto il controllo dell'Esercito bulgaro. Tra le comunità religiose locali che resistevano a questa nuova ondata denazionalizzatrice, questa volta bulgara, si distingueva un'altra volta la comunità di Prilep, che rifiutò di sottomettersi all'Esarcato bulgaro e riuscì a mantenere il proprio controllo sulla scuola locale. La resistenza patriottica contro l'Esarcato, fu diretta a Prilep dal prete locale macedone Spase Igumenov. Egli si fece promotore di una petizione, firmata da ventisei cittadini di Prilep inviata al sultano Abdul Hamid. Il testo del documento è breve ma chiaro: " Dichiarazione Noi sottoscritti della città di Prilep, sudditi di Sua Altezza Imperiale, augusto sultano Abdul Hamid II, desideriamo avere la scuola nazionale macedone. E non essendo noi dei bulgari, non riconosciamo la Comunità Ecclesiastica Bulgara né le scuole. Per la protezione religiosa noi riconosciamo il Papa, ma senza mutare i dogmi della Chiesa Ortodossa"...

- ^ The Macedonian Times. Skopje: MI-AN. 1998. p. 33.

'We, the undersigned from the city of Prilep, subjects of His Imperial Majesty, the august Sultan Abdul Hamid II, wish to have a national Macedonian school. And since we are not Bulgarians, we do not recognize the Bulgarian Ecclesiastical Community and schools. We recognize the Pope with respect to religious protection, however without changing the dogmas of the Orthodox Church.' July 2, 1887 (a seal) Dimche Trapkov, Dime Talev, Georgos Hriz, Ace Todor, Dame Ile, Posva Jankov, Cvetan, Ico Chutan, Jose Azarche, Tale Kostov, Kone Naprov, Jona Ilar, Jovan Menir, Nikola Jonov, Mirche Bozhino , Father Spase Igumenov, Todor V. Pantov, Ace Trajkov, Ice Josov , Risto Konev, Janko Tanov a teacher, Ognan Dimov, Todo Krapche, Kone Dimov, Grujo and Kono Narazov.

- ^ Мария Полимирова, Цетинските инкунабули в България, В Дългият осемнадесети век, Книгите като събития в Европа и Османската империя (ХVІІ–ХІХ в.), редактор/и: Н. Александрова, Р. Заимова, А. Алексиева, 2020, стр. 130-155, ISSN (online): 2603-4492, ISBN 978-619-91614-0-1.

- ^ Ethnic rivalry and the quest for Macedonia, 1870-1913. East European Monographs. 2003. p. 70.

- ^ Brancoff, D. M. La Macédoine et sa Population Chrétienne : Avec deux cartes etnographiques. Paris, Librarie Plon, Plon-Nourrit et Cie, Imprimeurs-Éditeurs, 1905. p. 148 – 149

- ^ HHS, PA, XXXVIII, t. 264, Saloniki, 7 September 1887, no. 88.

- ^ Rama, Shinasi A. (2019). Nation Failure, Ethnic Elites, and Balance of Power: The International Administration of Kosova. Springer. p. 90. ISBN 9783030051921.

- ^ Ташев, Ташо. Българската войска 1941 – 1945 – енциклопедичен справочник. „Военно издателство“. ISBN 978-954-509-407-1, стр. 173-174.

- ^ Square "Alexandria" on prilep.gov.mk

- ^ Marijiana Ricl, "New Greek Inscriptions from Pelagonia and Derriopos" Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 101 (1994) 151–163

- ^ Olteanu, Sorin. "Tabula Peutingeriana - C - Ceramiae VII 1 m". Sorin Olteanu's Thracology. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015.

- ^ IG X,2 2 233 Northern Greece (IG X), Macedonia, Pelagonia, Kolobaise (Treskavec)

- ^ "Climate data for Prilep, Macedonia". Weatheronline.co.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ "за нас". tkprilep.com.mk (in Macedonian). Tutunski Kombinat Prilep. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

External links

[edit]- Прилеп, Prilep

- Official Prilep Municipality website

- Prilep at the Balkan Info Home website

- "St. Kliment Ohridski" University - Bitola

- Prilep at the Cyber Macedonia website

- "Asterisks": International children's music festival

- Стари фотографии од Прилеп

- Марко Цепенков

- Пеце Атанасоски

- Блаже Конески

- Gentherm