History of philosophy in Pakistan

The History of philosophy in Pakistan is the philosophical activity or the philosophical academic output both within Pakistan and abroad.[1][2] It encompasses the history of philosophy in the state of Pakistan, and its relations with nature, science, logic, culture, religion, and politics from antiquity in continuity after its establishment in August 1947.[3] Historically, the promulgation of Philosophy in what is now Pakistan has been in relation to Indian Philosophy as well as Persianate philosophy.[4][5]

In an editorial written by critic Bina Shah in Express Tribune in 2012, "the philosophical activities in Pakistan can nevertheless both reflects and shapes the collected Pakistani identity over the history of the nation."[6]

History

[edit]Ancient Era

[edit]The region that makes up Pakistan lies on the core of the Indus Basin, and has been inhabited in continuity for millennia, the earliest works of Philosophy done in Ancient India involved the Vedas and the Upanishads. The Rigveda, the first of the four Vedas, was composed around the Punjab region present in Modern Pakistan and Northwestern India, where early Vedic schools also existed. During the Vedic era, metaphysical concepts such as the ones on existence in the Nasadiya Sukta and on creation in the Hiraṇyagarbha Sūkta were prominent. The Vedic concept of cosmic order developed firstly among priest-philosophers dwelling along the Indus Basin, which provided the metaphysical foundation for later developments in the Dharmic traditions.

The renowned Institute of Ancient Taxila was established around the 6th century BC in the city of Taxila in Northern Punjab as seat of Jain philosophy, which evolved into a center of Buddhist and Vedic teachings as well as a hub of education in religious and secular topics in South Asia and beyond for centuries to come.[7][8] Gandhara in Northern Pakistan itself would continue to serve as a prominent center of philosophy in the Asian continent for many centuries.

Pāṇini | |

|---|---|

|

Pāṇini, an ancient Sanskrit Grammarian was born in the region of Modern Pakistan roughly around the 7th, 6th or the 4th century BC.[9] Considered the greatest linguist of antiquity, his primary work, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, brought forth an algorithmic approach to grammar and a formal model of language.[10] Since the exposure of European scholars to his works in the 19th century, Pāṇini has largely been considered the "first descriptive linguist" in history, and even labelled as "the father of linguistics".[11][12] His approach to grammar influenced such foundational linguists as Ferdinand de Saussure and Leonard Bloomfield.[13] The rigorous formal system developed by Pāṇini far predates the 19th century innovations of Gottlob Frege and the subsequent development of mathematical logic. Pingala, an ancient Indian mathematician is often considered by some to be his brother.[14]

During Alexander the Great's invasion of the Indus Valley, he encountered the Gymnosophists on the banks of the Indus River in Modern Pakistan.[15] Mentioned several times in Ancient Greek records, they were known for their extreme ascetic philosophy.[16] It was believed by Diogenes Laërtius (fl. 3rd century AD) that Pyrrho of Ellis, the founder of Pyrrhonism was deeply influenced by the gymnosophists while in India with Alexander the Great, and on his return to Ellis, developed his philosophy based on these gymnosophists.[17]

In the field of Mathematical philosophy, the invention of Zero holds major significance. The earliest known use of the numeral for Zero occurred in the Bakhshali manuscript, discovered in the Mardan district in Pakistan.[18] It is often considered "the oldest extant manuscript in Indian mathematics.[19]

Chankya, the purported author of the political treatise, the Arthashastra, and one of the earliest thinkers of Political Philosophy was believed to have been born in Gandhara.[20] Acting as the Prime Minister to Chandragupta, the founder of the Mauryan Empire, his text is considered among the oldest works on statecraft, economic policy, and law, acting as a guide to administering a kingdom.[21]

Greater Gandharan Philosophy

[edit]With the rise of Buddhism and the subsequent synthesis of Hellenistic culture in Pakistan, a new type of philosophy emerged in what is now Pakistan, Afghanistan and Northwestern India, called the Greco-Buddhist or the Gandharan Buddhist philosophy.[22][23] As philosophy flourished, it was spread to various corners of Asia via the Silk Road connection. Taxila became an attractive seat of learning for people from various different nations.

The Milindapañha, composed in Sialkot (then known as Sagala) was a widely prominent philosophical text detailing a debate between the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Milinda) and a Buddhist sage Nagasena. Thomas Rhys Davids considered it the greatest work of classical Indian prose, he says:

"[T]he 'Questions of Milinda' is undoubtedly the masterpiece of Indian prose, and indeed is the best book of its class, from a literary point of view, that had then been produced in any country."[24]: xlvi

The background depiction given by the records of the text show that the region of Gandhara and Punjab were at that time, prominent centers of learning for all forms of philosophy, with Buddhist philosophy being the dominant form among them.

Vasubandhu and Asanga, two half-brothers likely born around Peshawar, remain some of the most influential Buddhist philosophers to date.[25][26] Vasubandhu's works set forth the standard for the Yogacara metaphysics of "appearance only" (vijñapti-mātra), which has been described as a form of "epistemological idealism", phenomenology[27] and close to Immanuel Kant's transcendental idealism.[28] In Jōdo Shinshū (the largest branch of Japanese Buddhism), he is considered the Second Patriarch; in Chan Buddhism (the originating tradition of Zen), he is the 21st Patriarch.[29] Similarly, Asanga's works were also influential in the Abhidharma tradition, and his Maitreya Corpus in turned influenced Buddhism in China, Korea and Japan.[30][31] Together, these half-brothers were considered as some of the foremost figures in Mahayana philosophy.[32]

Philosophies like hetuvidyā (logic and epistemology), vyākaraṇa (linguistics), śīla (ethics), and tattvavidyā (metaphysics) remained influential during the Gandharan period.[33][34]

Muslim Era

[edit]Via the Sufi missionaries from Persia and Central Asia, Islam was spread into the lands of the Indus Basin during the early medieval period, converting a majority of the regional Buddhist and Hindu population to Islam.[35] Ali al-Hujwiri, a migrant from Persia to Punjab, became some of the earliest Muslim mystic philosophers in the region.[36] A Punjabi Muslim mystic named Farīduddīn Masūd Ganjshakar (known commonly as Baba Farid) was among the earliest figures of Muslim philosophy in the present region of Punjab.[37] Venerated by Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs alike,[38] he remains one of the most revered Muslim mystics from South Asia during the Islamic Golden Age.[39]

As the Islamic Golden Age began, the region of Modern Pakistan played an important role in its promulgation. Abu Ali al-Sindhi, the tutor of Bayazid Bastami, is thought to have brought the concept of Fana to his student. Whereas, Kankah of Sindh, a prominent Astronomer of the time was among the earliest translators of Indic philosophical and scientific texts into Arabic for the Caliphate. Meanwhile, mathematics and logic were further promoted by people belonging to the Indus Basin. [40]

During the Middle ages, philosophy in the region of Modern Pakistan focused primarily on Islamic Mysticism. However, a trend of Humanism can be seen during the Middle Ages. Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai from Sindh was known for his metaphysical romanticism and symbolic philosophy.[41][42] Similarly, Bulleh Shah from Punjab, considered the 'Father of Punjabi Enlightenment', opposed religious orthodoxy and remains one of the most influential humanistic philosophers from South Asia.[43][44]

During the late middle era Sachal Sarmast engaged in a Persian-Sindhi metaphysical synthesis and defended Ibn Arabi’s ideas, popularizing these concepts in Sindh.[45]

Colonial Era

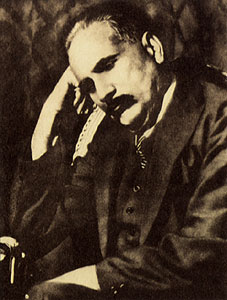

[edit]Philosophy in Pakistan declined during the Colonial era with the destruction of old institutions.[46] As the British colonized South Asia, new thoughts began to emerge. The most prominent figure during this was Sir Muhammad Iqbal. Widely considered one of the most important and influential Muslim thinkers and Islamic religious philosophers of the 20th century, his vision of a cultural and political ideal for the Muslims of British India is widely regarded as having animated the impulse for the Pakistan Movement.[47] Inspired by the Aligarh Movement, Philosophy among the Muslims of India in general was mostly political and reactionary during this era, aimed at safeguarding the future of the Indo-Islamic heritage.[48] Pakistan Movement itself was a product of young Nationalist thinkers such as Chaudhry Rehmat Ali.

Post-Independence

[edit]When Pakistan gained independence there was only one philosophy department in the country, at Government College Lahore.[49] Academically, philosophical activities began in the universities, and with the thought organization founded by philosopher M.M. Sharif, a pupil of G. E. Moore, in 1954.[1] M.M. Sharif himself was an Analytic philosopher who delved into Post-Modern thought. An active figure in the Pakistan Movement, he was deeply interested in realism and attempted to synthesize Modern Muslim thought with Western Philosophy.[50]

C.A. Qadir, born in Sialkot, was another Pakistani Analytic philosopher and psychologist. A critical student of Islamic philosophy, he wrote over thirty books on philosophy, ethics, and psychology.[51]

Between the 1960s and the 1980s, Socialist philosophy, although repressed, began to gain popularity in Pakistan. Figures like Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Habib Jalib and Rusool Bux Palijo were among the prominent Socialist thinkers in Pakistan.

Malik Meraj Khalid, the caretaker prime minister of Pakistan from November 1996 to February 1997, and the fifth Chief Minister of Punjab from 1972 to 1973, was a Marxist Philosopher and one of the founding figures of the Pakistan People's Party.[52] Around the early 1990s, he left politics and entered a period of solitude, becoming the Rector of International Islamic University in Islamabad in 1997.[53]

Today, philosophy is taught as a subject in most universities in Pakistan, and as an optional subject in Pakistani high schools in 11th and 12th grade.[54]

Notable figures

[edit]Notable Pakistani philosophers include:

References

[edit]- ^ a b Richard V. DeSemet; et al. "Philosophical Activities in Pakistan:1947-1961". Work published by Pakistan Philosophical Congress. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Kazmi, A. Akhtar. "Quantification and Opicity". CVRP. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Ahmad, Naeem, ed. (1998). Philosophy in Pakistan. Washington, DC: Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. ISBN 1-56518-108-5. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23.

- ^ "Timeless Legacy: Persian And Central Asian Influence In Pakistan". 2025-05-26. Retrieved 2025-11-05.

- ^ "Indian philosophy - Neo-Vedanta, Advaita, & Nyaya | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2025-11-05.

- ^ Shah, Bina (November 21, 2012). "Philosophy of Pakistan". Express Tribune, 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Marshall, John (1951). Taxila: An Illustrated Account of Archaeological Excavations. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 207–209.

- ^ Mehmood, A.; Shahid, A.M. "Digital reconstruction of Buddhist historical sites (6th B.C-2nd A.D) at Taxila, Pakistan (UNESCO, world heritage site)". Proceedings Seventh International Conference on Virtual Systems and Multimedia. IEEE Comput. Soc: 177–182. doi:10.1109/vsmm.2001.969669.

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (1999). Dharmasutras. Oxford University Press. pp. xxvi–xxvii. ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7.

- ^ Lowe, J.J. (2024). Modern Linguistics in Ancient India. Cambridge University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-009-36450-8.

- ^ François & Ponsonnet (2013: 184).

- ^ Pāṇini; Böhtlingk, Otto von (1998). Pāṇini's Grammatik [Pāṇini's Grammar] (in German) (Reprint ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1025-9.

- ^ Robins, Robert Henry (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London: Longman. ISBN 0582249945. OCLC 35178602.

- ^ François & Ponsonnet (2013: 184).

- ^ Plutarch. Life of Alexander, Parallel Lives. pp. 64–65.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gymnosophists". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 753–754.

- ^ (ix. 61 and 63)

- ^ "Earliest recorded use of zero is centuries older than first thought | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2025-11-05.

- ^ Takao Hayashi (2008), "Bakhshālī Manuscript", in Helaine Selin (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, vol. 1, Springer, pp. B1 – B3, ISBN 9781402045592

- ^ Trautmann 1971, p. 12.

- ^ Olivelle 2013, pp. 1–5, 24–25, 31.

- ^ Rengel, Marian (2003-12-15). Pakistan: A Primary Source Cultural Guide. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. pp. 59–62. ISBN 978-0-8239-4001-1. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Buddhism In Pakistan". pakteahouse.net. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

RhysDavidswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ History of philosophy in Pakistan at the Encyclopædia Britannica. "Asaṅga, (flourished 5th century AD, b. Puruṣapura, India), influential Buddhist philosopher who established the Yogācāra (“Practice of Yogā”) school of idealism."

- ^ Engle, Artemus (translator), Asanga, The Bodhisattva Path to Unsurpassed Enlightenment: A Complete Translation of the Bodhisattvabhumi, Shambhala Publications, 2016, Translator's introduction.

- ^ Lusthaus, Dan (2002). Buddhist Phenomenology: A Philosophical Investigation of Yogācāra Philosophy and the Ch'eng Wei-shih lun. New York, NY: Routledge.

- ^ Gold, Jonathan C. (2015). ""Vasubandhu"". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Niraj Kumar; George van Driem; Phunchok Stobdan (18 November 2020). Himalayan Bridge. KW. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-1-00-021549-6.

- ^ Ruegg, D.S. La Theorie du Tathagatagarbha et du Gotra. Paris: Ecole d'Extreme Orient, 1969, p. 35.

- ^ Lugli, Ligeia, Asaṅga, oxfordbibliographies.com, LAST MODIFIED: 25 NOVEMBER 2014, DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780195393521-0205.

- ^ Rahula, Walpola; Boin-Webb, Sara (translators); Asanga, Abhidharmasamuccaya: The Compendium of the Higher Teaching, Jain Publishing Company, 2015, p. xiii.

- ^ Peters, Michael A. (2019-09-19). "Ancient centers of higher learning: A bias in the comparative history of the university?". Educational Philosophy and Theory. 51 (11): 1063–1072. doi:10.1080/00131857.2018.1553490. ISSN 0013-1857.

- ^ "Educational System of Ancient India | Gurukulas and Learning". muhammadencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2025-11-06.

- ^ Ira Marvin Lapidus (2002). A history of Islamic societies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 382–384. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- ^ Hosain, Hidayet and Massé, H., "Hud̲j̲wīrī", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs: "Iranian mystic, born at Hud̲j̲wīr, a suburb of G̲h̲azna... Although he was a Sunni and a Hanafi...".

- ^ Pemberton, Barbara (2023). "Polishing the Mirror of the Heart: Sufi Poetic Reflections as Interfaith Inspiration for Peace". In Shafiq, Muhammad; Donlin-Smith, Thomas (eds.). Mystical Traditions: Approaches to Peaceful Coexistence. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. pp. 263–276. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-27121-2_15. ISBN 978-3-031-27121-2.

Punjabi shaykh Farid al-Din Ganj-i-Shakar ( 1179–1266 ) opines

- ^ Singh, Paramjeet (2018-04-07). Legacies of the Homeland: 100 Must Read Books by Punjabi Authors. Notion Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-64249-424-2.

- ^ Khaliq Ahmad Nizami (1955). The Life and Times of Shaikh Farid-u'd-din Ganj-i-Shakar. Department of History, Aligarh Muslim University. p. 1.

- ^ Nizam, Muhammad Huzaifa (2023-01-15). "HOW THE INDUS VALLEY FED ISLAM'S GOLDEN AGE". Dawn. Retrieved 2025-11-06.

- ^ Buriro, Hakim Ali; Saeed, Saima; Latif, Wasif (2023-06-30). "Concept of Humanism in Shah Abdul Latif's Bhattai Poetry". Makhz (Research Journal). 4 (2): 14–23. ISSN 2709-9644.

- ^ Correspondent, The Newspaper's Staff (2018-12-10). "Shah Latif's philosophy termed relevant today". Dawn. Retrieved 2025-11-06.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Mara Brecht; Reid B. Locklin, eds. (2016). Comparative theology in the millennial classroom : hybrid identities, negotiated boundaries. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-51250-9. OCLC 932622675.

- ^ J.R. Puri; T.R. Shangari. "The Life of Bulleh Shah". Academy of the Punjab in North America (APNA) website. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Admin (2025-09-26). "Sachal Sarmast – A Sufi Saint of Sindh - IBEX TIMES". Retrieved 2025-11-06.

- ^ Momen, Abdul; Ebrahimi, Mansoureh; Yusoff, Kamaruzaman (2024-08-07). "British Colonial Education in the Indian Subcontinent (1757-1858): Attitude of Muslims". Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization. 14 (1): 17–39. doi:10.32350/jitc.141.02. ISSN 2520-0313.

- ^ "Muhammad Iqbal - Poet, Philosopher, Reformer | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2025-11-05. Retrieved 2025-11-06.

- ^ "equal rights". Off Our Backs. 25 (1): 4–4. 1995. ISSN 0030-0071.

- ^ Ahmad, Naeem. "Philosophy in Pakistan".

- ^ De Smet, S.J., Richard V. "Philosophical activity in Pakistan: 1947–1961". De Nobili College, Poona, India. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "C. A. Qadir". Retrieved 26 November 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Arif Azad (31 July 2003). "Obituary Malik Meraj Khalid". The Guardian (newspaper). London. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Arif Azad (31 July 2003). "Obituary Malik Meraj Khalid". The Guardian (newspaper). London. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Intermediate Subjects".

Further reading

[edit]- DeSemet, Richard. Philosophical activity in Pakistan. Pakistan Philosophical Congress. p. 132. LloZAAAAMAAJ.

- Javed, Kazi. Philosophical Domain of Pakistan (Pakistan Main Phalsapiana Rojhanat) (in Urdu). Karachi: Karachi University Press.

- Nasr, ed. by Seyyed Hossein Nasr (2002). History of Islamic philosophy (Repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Routledge. ISBN 0415131596.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Ahmad, Naeem, ed. (1998). Philosophy in Pakistan. Washington, DC: Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. ISBN 1-56518-108-5. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23.

- Stepaniants, Mariėtta Tigranovna (1972). Pakistan: Philosophy and Sociology. Karachi, Sindh: People's Publishing House. XfUSAAAAMAAJ.

- Ishrat, Waheed (2007). Understanding Iqbal's philosophy. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications. ISBN 978-9693520736.