History of KFC

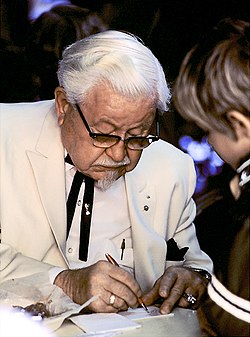

KFC (also known as Kentucky Fried Chicken) was started by Colonel Sanders, who began selling fried chicken from his gas station in Corbin, Kentucky, during the Great Depression. Sanders saw that franchising had great potential, and the first official franchise opened in Utah in 1952. KFC helped make chicken popular in fast food, providing an alternative to the common hamburger. Sanders became a famous American figure by branding himself as "the Colonel," and his face is still used in ads today. The company grew so fast that Sanders could not manage it alone, so in 1964 he sold it to a group led by John Y. Brown Jr. and Jack C. Massey.

KFC was an early leader in international expansion, opening stores in Britain, Mexico, and Jamaica by the mid-1960s. During the 1970s and 80s, the company had mixed results in the U.S. as it changed owners several times. It was first sold to the drinks company Heublein, which was later bought by the R. J. Reynolds tobacco group, before finally being sold to PepsiCo. Despite these changes, the chain kept growing globally and became the first Western fast-food brand to open in China in 1987.

In 1997, PepsiCo turned its restaurant business into a separate company called Tricon, which was renamed Yum! Brands in 2002. Yum! has been a more successful owner, and while KFC has fewer locations in the U.S. now, it is growing rapidly in Asia, South America, and Africa. There are now over 18,800 outlets in 118 countries, with China being the company’s biggest market.

Origin of Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC)

[change | change source]Harland Sanders was born in 1890 and grew up on an Indiana farm.[1] After his father died in 1895, Sanders had to help care for his siblings while his mother worked.[2] He learned to cook at age seven and later worked various jobs, like selling insurance and working on the railroad.[1][3] In 1930, he began running a Shell gas station outside North Corbin, Kentucky.[4] He started serving simple meals like steak and ham to travelers on his own dining table.[5]

Sanders moved to a more visible gas station across the road in 1934 and began selling fried chicken.[6][7] He took a short course at Cornell University to learn more about managing a restaurant.[8] By 1936, his success led the governor to name him a Kentucky colonel.[9] He expanded his dining area to 140 seats and bought a motel nearby, which he called the Sanders Court & Café.[10]

Sanders didn't like how long it took to cook chicken in a pan, but he thought deep frying made the meat too dry. He began using a modified pressure cooker to fry his chicken faster while keeping it moist.[11][12] In 1940, he finished his "Original Recipe" of 11 herbs and spices.[13] He never shared the secret ingredients, though he said they were common items found in most kitchens.[10][14] By 1950, he began wearing his famous white suit and goatee, fully embracing the "Colonel" persona.[15]

Early franchisees of KFC

[change | change source]When a new highway bypassed his town in 1955, Sanders sold his business and traveled the country to sell his chicken recipe to other restaurant owners.[16] Owners would pay him a small fee for every chicken sold using his secret blend and branding.[1][17] His first partner was Pete Harman in Salt Lake City, whose restaurant sales shot up after adding the chicken.[18] The name "Kentucky Fried Chicken" was actually created by a sign painter Harman hired, as it made the food sound like exotic Southern hospitality.[19]

Early partners were vital to the chain's growth. Harman created the slogan "It's finger lickin' good" and introduced the famous cardboard bucket meal in 1957.[17][19] Another early franchisee was Dave Thomas, who later founded Wendy's. Thomas helped design the rotating bucket sign and created a better system for keeping track of sales.[20][21] To better distribute supplies and ads to his partners, Sanders moved the company's main office to Shelbyville, Kentucky, in 1956.[1][8]

Sale by Sanders and rapid growth

[change | change source]KFC changed the fast-food world by making chicken a major competitor to the burger.[22] By 1963, there were 600 stores, making it the biggest fast-food chain in the U.S.[16] Sanders decided to sell the company in 1964 for $2 million to a group of investors led by John Y. Brown Jr. and financier Jack C. Massey.[23][9] The deal gave Sanders a salary for life and made him the official face of the brand.[24]

The new owners standardized the restaurants, using the red-and-white stripes and special roofs we see today.[25][26] Even after selling, Sanders often argued with the executives when he felt they were making poor decisions.[1] He was upset when they moved the headquarters out of Kentucky and fought for the rights to run the business in Canada.[27][28] The company eventually went public in 1966.[29]

By the late 1960s, KFC was expanding rapidly to stay ahead of rivals like Church's Chicken.[30] The stock price soared, and the chain was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1969.[31] [32] However, some side projects like roast beef restaurants and motels failed.[33] International growth was also difficult at first; the first store in Japan was a huge failure in its first month.[34] By 1971, the company was struggling with its first financial loss.[35]

Heublein and strained relations with Sanders; R. J. Reynolds

[change | change source]

KFC grew so quickly that it eventually became too difficult for John Y. Brown to manage, just as it had for Harland Sanders.[32] In July 1971, Brown sold the company to Heublein, a food and drink corporation based in Connecticut, for US$285 million.[36] While Brown personally earned $35 million from the deal, some experts believed the takeover was necessary to save the company from potential disaster.[37][32] Heublein intended to use its marketing and sales experience to grow the brand further.[38]

During this period, Church's Chicken challenged KFC by offering indoor seating and a "Crispy Chicken" product.[39] KFC responded by introducing "Extra Crispy Chicken" in 1972.[40] However, an attempt to sell barbecue spare ribs in 1973 failed due to pork shortages and high costs, which led to the product being pulled from the menu.[39][41] At the same time, Sanders regretted selling the company and his relationship with the new owners turned sour as he publicly criticized the declining food quality.[39][42]

- My God, that gravy is horrible! They buy tap water for 15–20 cents a thousand gallons and then they mix it with flour and starch and end up with pure wallpaper paste ... And another thing. That new crispy recipe is nothing in the world but a damn fried doughball stuck on some chicken.[43]

These comments led to legal disputes, including a libel suit from a franchisee and a trademark battle between Heublein and Sanders over his new restaurant, "Claudia Sanders, the Colonel's Lady Dinner House".[10][44] Sanders also sued Heublein for $122 million for misusing his image to promote products he didn't help create.[45] They eventually settled out of court for $1 million in 1975, and Sanders was permitted to keep his restaurant under the name "Claudia Sanders Dinner House".[44]

Heublein lacked experience in fast food, which led to the chain failing in overseas markets like Hong Kong by 1975.[39][46] Sanders continued to publicly criticize the company's poor quality products, and by 1978, KFC’s company-owned stores were no longer profitable.[47][39] To fix the business, Heublein appointed Michael A. Miles in 1977, who saved the company by returning to a "back-to-basics" approach.[48] Miles updated stores, added drive-thrus, and improved inventory tracking, while also listening to Sanders' recommendations.[39][48] These changes led to a period of steady sales growth and international expansion into countries like Japan and the UK.[39][49]

Sanders passed away from pneumonia in 1980 at age 90, having spent his final years traveling extensively to promote the brand. [50] [51] He remains a central figure in American culture and the primary image for KFC advertising.[22] By 1983, the chain had grown to 5,800 outlets in 55 countries.[52] To prevent a hostile takeover, Heublein merged with the tobacco firm R. J. Reynolds for $1.3 billion.[53] During this time, KFC launched "Kentucky Nuggets" to compete with McDonald's new McNuggets.[54][55]

Acquisition by PepsiCo

[change | change source]In July 1986, Reynolds sold KFC to PepsiCo for $850 million so it could focus on its tobacco and food business.[56][57] Analysts had different views on the sale, with some believing the chain had been neglected and others feeling it had been well-revived by Reynolds.[58][59] PepsiCo used the acquisition to boost soft drink sales, causing several competitors like Wendy's and Burger King to switch from Pepsi to Coca-Cola.[59][60][61][62] By 1987, KFC opened its first Western outlet in Beijing, China, and by 1989, sales were growing significantly.[63][64]

International growth and franchisee disputes under John Cranor III

[change | change source]

John Cranor III became CEO in 1989 and immediately faced a major contract dispute with franchisees that lasted until 1996.[65][66][67] Despite this, Cranor invested millions in restructuring global operations, updating store technology, and expanding into non-traditional locations.[68] The chain grew to 8,500 outlets by 1991 but struggled to compete with the rising popularity of grilled chicken burgers from rivals like Burger King.[68][65][58]

In 1991, the company officially adopted the "KFC" name to move away from the unhealthy image of "fried" food and reflect its broader menu.[69][70][71] Successes followed with the launch of "Hot Wings," popcorn chicken, and the "Zinger" burger abroad, but health-focused products like rotisserie and skinless chicken failed to gain traction.[72][73][74] While U.S. sales were weak, international markets thrived, especially in Asia, where KFC became the leading Western fast food chain in countries like China and Indonesia.[62][75][76]

David Novak appointed President

[change | change source]By 1994, KFC had over 9,400 outlets but was losing ground to McDonald's and its value menu.[77][78] David C. Novak was appointed President of KFC North America in 1994 to revive the brand.[79] He improved the company's relationship with franchisees and worked with them to launch successful new items like Crispy Strips and chicken pot pie.[78][80] Novak also streamlined the menu by removing unpopular items and reduced friction between KFC and sister brands Taco Bell and Pizza Hut.[81]

In 1996, the company finally resolved its long-standing legal feud with franchisees by restoring their original contract protections.[82] Novak also replaced the failed rotisserie chicken with a new non-fried product called "Tender Roast," which was sold by the piece to better align with the chain’s traditional offerings.[74]

David Novak led KFC North America to grow for ten quarters in a row. Because of this success, he was named president and CEO of the whole KFC company in 1996.[83][84]

Spin-off as Tricon (later Yum! Brands)

[change | change source]

In August 1997, PepsiCo separated its restaurant branch into a new public company worth $4.5 billion.[85] While KFC was doing well, PepsiCo's other brands, Pizza Hut and Taco Bell, were struggling. One executive admitted that running restaurants was not their specialty.[86] The new company was named Tricon Global Restaurants. With 30,000 locations, it became the second-largest food seller in the world after McDonald's.[87]

Since 2000, fast food has faced criticism over how animals are treated, its role in obesity, and its harm to the environment.[88] Books like Fast Food Nation and the movie Super Size Me highlighted these worries. Since 2003, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) has protested KFC's chicken suppliers. PETA has held many rallies, and once a protester even poured fake blood on CEO David Novak.[89][90] KFC responded by saying they buy chicken rather than raise them, but Yum! promised to monitor their suppliers more closely to ensure animals are treated well.[91][92]

Tricon changed its name to Yum! Brands in 2002.[93] That year, KFC struggled against new chicken sandwiches from Burger King and fried chicken from pizza chains like Domino's. KFC sales dropped as the brand began to look outdated. A roast chicken line in 2004 failed, and a bird flu scare in 2005 caused sales to drop by up to 40 percent.[94] To fix this, KFC launched the "Snacker," a small, cheap burger that sold over 100 million units. They also updated their look by using the full "Kentucky Fried Chicken" name again and making Colonel Sanders' face more prominent in stores.[95]

KFC continued to try new items to attract younger customers, like the Krusher frozen drinks in 2009. In 2010, they launched the Double Down, which used two pieces of fried chicken instead of bread. While criticized for being unhealthy, it was very popular, with 15 million sold in two years.[96][97] In 2013, KFC tried a more upscale restaurant called KFC Eleven, but it closed in 2015.[98]

By the end of 2013, KFC had over 18,800 stores in 118 countries, making it the world's second-largest restaurant chain. Even though sales in China dropped in 2013, they began to recover the next year.[99][100] However, in July 2014, a food safety scandal broke out when a supplier in Shanghai was accused of providing expired meat. Yum! stopped using that supplier, but the news caused a big drop in sales in China.[101][102]

References

[change | change source]- 1 2 3 4 5 Whitworth, William (February 14, 1970). "Kentucky-Fried". New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ↑ Klotter, James C. (2005). The Human Tradition in the New South. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 129–136. ISBN 978-0-7425-4476-5. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ↑ Sanders, Harland (2012). The Autobiography of the Original Celebrity Chef (PDF). Louisville: KFC. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013.

- ↑ "US Geological Survey Map from 1952". Archived from the original on June 18, 2023. Retrieved June 18, 2023.

- ↑ Ozersky, Josh (2012). Colonel Sanders and the American Dream. University of Texas Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-292-74285-7.

- ↑ Sanders, Harland (2012). The Autobiography of the Original Celebrity Chef (PDF). Louisville: KFC. p. 39. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013.

- ↑ Sanders, Harland (2012). The Autobiography of the Original Celebrity Chef (PDF). Louisville: KFC. p. 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013.

- 1 2 Smith, J. Y. (December 17, 1980). "Col. Sanders, the Fried-Chicken Gentleman, Dies". Washington Post.

- 1 2 Smith, Andrew F. (December 2, 2011). Fast Food and Junk Food: An Encyclopedia of What We Love to Eat. ABC-CLIO. p. 612. ISBN 978-0-313-39394-5. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Kleber, John E.; Thomas D. Clark; Lowell H. Harrison; James C. Klotter (June 1992). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. University Press of Kentucky. p. 796. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- ↑ Sanders, Harland (1974). The Incredible Colonel. Illinois: Creation House. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-88419-053-0.

- ↑ Grimes, William (August 26, 2012). "From Colonel Sanders: Roots And Chicken". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ↑ Schreiner, Bruce (July 23, 2005). "KFC still guards Colonel's secret". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ↑ Sanders, Harland (2012). The Autobiography of the Original Celebrity Chef (PDF). Louisville: KFC. p. 42. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013.

- ↑ Ozersky, Josh (2012). Colonel Sanders and the American Dream. University of Texas Press. pp. 35–6. ISBN 978-0-292-74285-7.

- 1 2 John A. Jakle; Keith A. Sculle (1999). Fast Food: Roadside Restaurants in the Automobile Age. JHU Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-8018-6920-4. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- 1 2 Liddle, Alan (October 14, 1996). "Leon W. 'Pete' Harman: the operational father of KFC has many goals — and retiring isn't one of them". Nation's Restaurant News. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ↑ Nii, Jenifer K. (2004). "Colonel's landmark KFC is mashed". Deseret Morning News. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- 1 2 Liddle, Alan (May 21, 1990). "Pete Harman". Nation's Restaurant News.

- ↑ Wepman, Dennis. "Dave Thomas". American National Biography Online. Archived from the original on January 4, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ↑ Thomas, R. David (October 1, 1992). Dave's Way: A New Approach to Old-Fashioned Success. Penguin Group (USA) Incorporated. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-425-13501-3. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- 1 2 Smith, Andrew F. (May 1, 2007). The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Oxford University Press. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-19-530796-2. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ↑ Demaret, Kent (October 22, 1979). "Kissin', but Not Cousins, John Y. and Phyllis George Aim to Do Kentucky Up Brown". People Magazine. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ↑ Cottreli, Robert (December 17, 1980). "Obituary: Colonel Sanders". Financial Times.

- ↑ Carey, Bill (September 30, 2005). Master of the Big Board: The Life, Times And Businesses of Jack Massey. Cumberland House Publishing. pp. 64–72. ISBN 978-1-58182-471-1. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ↑ "KFC Corporation". Company Profiles for Students. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ↑ Klotter, James C. (2005). The Human Tradition in the New South. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 150–152. ISBN 978-0-7425-4476-5.

- ↑ Sanders, Harland (1974). The Incredible Colonel. Illinois: Creation House. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-88419-053-0.

- ↑ Sanders, Harland (1974). The Incredible Colonel. Illinois: Creation House. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-0-88419-053-0.

- ↑ Coomes, Steve (March 11, 2014). "John Y. Brown Jr.: Colonel's sale of KFC 50 years ago changed restaurant industry forever". Insider Louisville. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ↑ Carey, Bill. "Sweet taste of success" (PDF). The Tennessee Magazine (April 2007). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Kentucky Fried to Add Grilled Chicken Items to Menu". Los Angeles Times. Reuters. November 23, 1989. Archived from the original on September 23, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ↑ Ozersky, Josh (2012). Colonel Sanders and the American Dream. University of Texas Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-292-74285-7.

- ↑ Alkhafaji, Abbass F. (March 1, 2003). Strategic Management: Formulation, Implementation, and Control in a Dynamic Environment. Psychology Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-7890-1810-6. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Kentucky Chicken reports a deficit". The New York Times. July 2, 1971.

- ↑ Barmash, Isadore (July 23, 1971). "Chief Expected to Leave Kentucky Fried Chicken". The New York Times.

- ↑ Brenner, Marie (November 16, 1981). "John Y. and Phyllis- Kentucky-Fried Style". Newyorkmetro.com. New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC: 45. ISSN 0028-7369. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ Sanders, Harland (1974). The Incredible Colonel. Illinois: Creation House. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-88419-053-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Heublein sees growth in food". The New York Times. November 12, 1980.

- ↑ Hiss, Anthony (May 19, 1975). "Curmudgeon Ribs Chickens". New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ↑ Business Week Issues 2490–2498. McGraw-Hill. 1977. p. 65. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ↑ Thomas, R. David (October 1, 1992). Dave's Way: A New Approach to Old-Fashioned Success. Penguin Group (USA) Incorporated. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-425-13501-3. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ↑ Sanford, Bruce W. (2004). Libel and Privacy. Aspen Publishers Online. pp. 4–17. ISBN 978-0-7355-5297-5. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- 1 2 United Press International (September 12, 1975). "Col. Sanders' Chicken War Ends". The New York Times. p. 46.

- ↑ "Colonel Sanders Is Suing Heublein For $122 million". The New York Times. January 16, 1974.

- ↑ Cho, Karen (March 20, 2009). "KFC China's recipe for success". Insead Knowledge. Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ↑ Sheraton, Mimi (September 9, 1976). "For the Colonel, It Was Finger-Lickin' Bad". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Sammons, Donna (March 2, 1980). "Kentucky Fried Chicken Can Cackle Again". The New York Times.

- ↑ Krug, Jeffrey A. Kentucky Fried Chicken and the Global Fast-Food Industry (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ↑ Lawrence, Jodi (November 9, 1969). "Chicken Big and the Citizen Senior". Washington Post.

- ↑ Ozersky, Josh (September 15, 2010). "KFC's Colonel Sanders: He Was Real, Not Just an Icon". Time. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ↑ "KFC Expansion". The New York Times. Reuters. May 5, 1983.

- ↑ Cannon, Carl (March 6, 1983). "All the Pieces in Place, Reynolds Will Focus on Internal Growth". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Goldsborough, Bob (November 26, 2013). "Michael A. Miles, 1939–2013". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- ↑ Delaney, Tom (June 3, 1985). "KFC Cooks Up New $80-Mil. Media Plan". ADWEEK.

- ↑ Stevenson, Richard W. (July 25, 1986). "Pepsico to Acquire Kentucky Fried: Deal Worth $850 Million". The New York Times.

- ↑ Brooks, Nancy Rivera (July 25, 1986). "Pepsico to Buy Kentucky Fried From RJR Nabisco". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- 1 2 Koeppel, Dan (September 3, 1990). "The Feathers Are Really Flying At Kentucky Fried". Adweek.

- 1 2 Giges, Nancy (July 28, 1986). "Kentucky Fried Chicken coup for PepsiCo". Advertising Age.

- ↑ Stevenson, Richard W. (July 25, 1986). "PepsiCo to acquire Kentucky Fried". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Wendy's Drops Pepsi For Coke". Financial Times. October 16, 1986.

- 1 2 Ramirez, Anthony (May 2, 1990). "New Coke Conquest: Burger King". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ↑ Jing, Jun (2000). Feeding China's Little Emperors: Food, Children, and Social Change. Stanford University Press. pp. 117–118, 127. ISBN 978-0-8047-3134-8. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ↑ Zagor, Karen (May 3, 1989). "PepsiCo Returns Sparkle". Financial Times.

- 1 2 Ramirez, Anthony (March 20, 1990). "Getting Burned By the Frying Pan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- ↑ Bob De Wit; Ron Meyer (April 9, 2010). Strategy: Process, Content, Context, An International Perspective. Cengage Learning EMEA. p. 918. ISBN 978-1-4080-1902-3. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ↑ "KFC, franchisees near to settling contract dispute". Nation's Restaurant News. February 5, 1996.

- 1 2 Montgomery, Cynthia A. (1994). PepsiCo's Restaurants. Harvard Business School Case 794-078. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Kentucky Fried Chicken redesigns for new image". Marketing News. March 18, 1991.

- ↑ Foulds, Peter (November–December 1993). "Revamping the image". Across the Board. 30 (9): 48–49.

- ↑ Kauffman, Matthew (March 5, 1999). "When Brand Image Falls From Favor". The Courant. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ↑ "A feast of bargains". Sunday Herald Sun. May 31, 1992.

- ↑ "KFC Makes Another Go at Roasted Chicken". QSR Magazine. April 28, 2004. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- 1 2 Kramer, Louise (March 4, 1996). "Rotisserie Gold plucked by KFC". Nation's Restaurant News.

- ↑ Tanzer, Andrew (January 18, 1993). "Hot Wings take off". Forbes.

- ↑ White, Michael (2009). Short Course in International Marketing Blunders: Marketing Mistakes Made by Companies that Should Have Known Better. World Trade Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-60780-008-8. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ↑ John A. Jakle; Keith A. Sculle (1999). Fast Food: Roadside Restaurants in the Automobile Age. JHU Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-8018-6920-4. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- 1 2 David E. Bell; Mary L. Shelman (November 2011). "KFC's Radical Approach To China". Harvard Business Review. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ↑ Prewitt, Milford (August 1, 1994). "Cranor resigns as KFC prexy, CEO". Nation's Restaurant News.

- ↑ Novak, David (January 26, 2012). Taking People with You: The Only Way to Make Big Things Happen. Penguin Books, Limited. ISBN 978-0-241-95413-3. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ↑ Benezra, Karen (October 30, 1995). "New Ideas On The Grill". Brandweek.

- ↑ Carlino, Bill (February 19, 1996). "KFC, franchisees settle lawsuit, agree to end bitter 7-year feud". Nation's Restaurant News.

- ↑ "Tricon: With All This Fizz, Who Needs Pepsi?". Business Week. October 18, 1998. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Executive Profile: David Novak". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on September 2, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Pepsico To Tricon". Chicago Tribune. October 7, 1997. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

- ↑ Tomkins, Richard (February 5, 1997). "PepsiCo hit by slump in international unit". Financial Times.

- ↑ "Pepsico Picks Name For Planned Spinoff". The New York Times. June 28, 1997. Archived from the original on May 5, 2013. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ↑ Barnett, Michael (December 16, 2010). "Colonel Sanders' new modern army of outlets". Marketing Week. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ↑ Yaziji, Michael; Doh, Jonathan (2009). "Case illustration: PETA and KFC". NGOs and Corporations: Conflict and Collaboration. Business, Value Creation, and Society. Cambridge University Press. pp. 112–114. ISBN 978-0-521-86684-2.

- ↑ Chuck Williams; Terry Champion; Ike Hall (2011). MGMT. Cengage Learning. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-17-650235-5. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ↑ Swann, Patricia (April 2010). Cases in Public Relations Management. Routledge. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-203-85136-4. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ↑ Annual Report (PDF). Louisville: Yum! Brands. 2008. p. 52. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 5, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Tricon Global Restaurants Shareholders Approve Company Name Change to Yum! Brands, Inc". QSR Magazine. May 16, 2002. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ↑ Buckley, Neil (July 15, 2004). "McDonald's gets lift from healthier eating food". Financial Times.

- ↑ "Yum! Brands: Fast food's yummy secret". The Economist. August 25, 2005. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ↑ Leung, Wency (April 13, 2010). "Forget healthy – KFC's Double Down revels in glorious gluttony". Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on May 11, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- ↑ "KFC Doubles Down in South Africa". QSR Magazine. March 26, 2013. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ↑ Elson, Martha (April 29, 2015). ""What now?" after Highlands KFC eleven closes". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Restaurant counts". Yum!. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ↑ "KFC owner Yum Brands' profit boosted by China recovery". BBC News. April 23, 2014. Archived from the original on April 23, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ↑ Hornby, Lucy (July 21, 2014). "McDonald's and KFC hit by China food safety scandal". Financial Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2014. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ Ramakrishnan, Sruthi (July 30, 2014). "Yum says China food safety scare hurting KFC, Pizza Hut sales". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

Other websites

[change | change source] Media related to Kentucky Fried Chicken at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kentucky Fried Chicken at Wikimedia Commons