Helicoprion

| Helicoprion Temporal range: Cisuralian–Guadalupian 290–270 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist's reconstruction | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | †Helicoprion Karpinsky, 1899 |

| Type species | |

| Helicoprion bessonowi Karpinsky, 1899 | |

Helicoprion is an extinct genus of shark-like[1] cartilaginous fish.

Almost all fossil specimens of this genus are of spirally arranged clusters of the individuals' teeth, called tooth whorls. In life, these were embedded in the lower jaw.

Like all chondrichthyan taxa, Helicoprion's skeleton was made of cartilage. Scientists know very little about what the skeleton looked like, because cartilage rarely fossilizes.

It was always assumed[by whom?] that the Helicoprion was a shark, but in reality, it is more closely related to ratfish.

Description

[change | change source]Because its skeleton was made of cartilage, the entire body of this fish disintegrated once it began to decay, unless preserved by exceptional circumstances. This can make it hard to draw illustrations of the full body appearance of Helicoprion.

The tooth was unusual-looking. It looked like a circular saw. The tooth is popularly known as a tooth whorl. The largest known Helicoprion tooth whorl, specimen IMNH 49382 representing an unknown species, reached 56 cm (22 in) in diameter and 14 cm (5.5 in) in crown height, which would have belonged to an individual over 7.6 m (25 ft) in length.

Some types of Eugeneodont fish with preserved postcrania include the Pennsylvanian to Triassic sharks Caseodus, Fadenia, and Romerodus.[2]

Tooth whorls

[change | change source]A tooth whorl is a structure found on Helicoprion. Almost all Helicoprion specimens are known solely from tooth whorls. They consist of many enameloid-covered teeth. The youngest and first tooth at the center of the spiral, referred to as the "juvenile tooth arch", is hooked, but all other teeth are generally triangular in shape, laterally compressed and often serrated.[3]

Other material

[change | change source]Several large whorls are difficult to assign to any particular species group, H. svalis among them. IMNH 14095, a specimen from Idaho, appears to be similar to H. bessonowi, but it has unique flange-like edges on the apices of its teeth. IMNH 49382, also from Idaho, has the largest known whorl diameter at 56 cm (22 in) for the outermost volution (the only one preserved), but it is incompletely preserved and still partially buried. H. mexicanus, named by F.K.G. Müllerreid in 1945, was supposedly distinguished by its tooth ornamentation.[4]

Species

[change | change source]- Helicoprion bessonowi Karpinsky, 1899 (type)

- Helicoprion davisii Woodward, 1886

- Helicoprion ergassaminon Bendix-Almgreen, 1966

H. bessonowi

[change | change source]H. bessonowi is perhaps the best-known species of this genus. It was not the first species of Helicoprion to be described, but it is the first one to be described from complete tooth whorls, which reveals Helicoprion is a distinct taxon from Edestus.[5] As a result, H. bessonowi serves as the type species for Helicoprion.[6]

H. davisii

[change | change source]The first specimen of this genus was discovered along a tributary of the Gascoyne River. Henry Woodward named it Edestus davisii, commemorating the man who found it.[7] Later, in 1899, Alexander Karpinsky reassigned it to the genus Helicoprion, and renamed it to H. davisii.[5]

H. ergassaminon

[change | change source]H. ergassaminon is known from the Phosphoria Formation of Idaho, just like H. davisii, though it is comparatively much rarer. H. ergassaminon was named and described in detail by Svend Erik Bendix-Almgreen.[8]

Historical depictions

[change | change source]

Earliest depictions

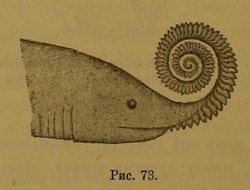

[change | change source]Hypotheses for the placement and identity of Helicoprion's tooth whorls were controversial from the moment it was discovered. Woodward (1886), who referred the first known Helicoprion fossils to Edestus, discussed the various hypotheses concerning the nature of Edestus fossils.

Karpinsky's hypothesis of the placement of the tooth whorl was putting it on the nose. Many people said that "the tooth whorl on the nose looks so weird."[source?] It now has its tooth whorl in its lower jaw.

Later depictions

[change | change source]By the mid-20th century, the tooth whorl was usually depicted as being on the lower jaw. The utility of the tooth whorl in this type of reconstruction was inferred based on sawfish, which have the ability to incapacitate and slice through prey using lateral blows of their spiky snouts.

In popular culture

[change | change source]Helicoprion was a famous animal because it has been found in many websites. People have given it the name buzzsaw shark.

Related pages

[change | change source]References

[change | change source]- ↑ Viegas, Jennifer (27 February 2023). "Ancient shark relative had buzzsaw mouth". science.nbcnews.com.

- ↑ "New eugeneodontid sharks from the Lower Triassic Sulphur Mountain Formation of Western Canada". Geological Society, London, Special Publications.

- ↑ "Saws, Scissors, and Sharks: Late Paleozoic Experimentation with Symphyseal Dentition". The Anatomical Record.

- ↑ "Unravelling species concepts for the Helicoprion tooth whorl" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-01.

- 1 2 Karpinsky, Alexander (1899). "On the edestid remains and the new genus Helicoprion". Notes of the Imperial Academy of Sciences.

- ↑ "Helicoprion from Elko County, Nevada". Journal of Paleontology.

- ↑ Woodward, Henry (1886). "On a Remarkable Ichthyodorulite from the Carboniferous Series, Gascoyne, Western Australia". Geological Magazine.

- ↑ "New investigations on Helicoprion from the Phosphoria Formation of south-east Idaho, USA" (PDF). Biol. Skrifter Udgivet Af Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab.

Other websites

[change | change source]![]() Media related to Helicoprion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Helicoprion at Wikimedia Commons