Elasmotherium

| Elasmotherium Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed E. caucasicum skeleton, Azov Museum of History, Archaeology and Palaeontology | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Subfamily: | †Elasmotheriinae |

| Genus: | †Elasmotherium Fischer, 1808[1] |

| Type species | |

| †Elasmotherium sibiricum Fischer, 1809

| |

| Other Species | |

| |

| |

| Approximate range map for Elasmotherium | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Elasmotherium (from Ancient Greek ἔλασμα (élasma), meaning "metal plate" with the intended meaning "lamina" in reference to the tooth enamel, and θηρίον (theríon), meaning "beast") is an extinct genus of very large rhinoceros that lived in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and East Asia from the late Miocene through to the Late Pleistocene, until at least 39,000 years ago. It was the last surviving member of the subfamily Elasmotheriinae, a formerly diverse group of rhinoceroses separate from the subfamily Rhinocerotinae, that contains all living rhinoceroses.

Five species are recognised. The genus first appeared in the Late Miocene in present-day China, likely having evolved from Sinotherium, before spreading to the Pontic–Caspian steppe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. Species of Elasmotherium are the largest known true rhinoceroses, reaching body lengths of at least 4.5 metres (15 ft), shoulder heights of over 2 metres (6 ft 7 in), and estimated body masses of 3.5–5 tonnes (7,700–11,000 lb), comparable to an elephant. The skull exhibits a large dome on the top of the skull roof, which is hollow and forms an enlargement of the nasal cavity. No remains of a horn of Elasmotherium have ever been found and the appearance of the horn, if any, has been subject to considerable speculation. Elasmotherium sibericum has often been conjectured and depicted as having borne an enormous nearly 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) long straight horn projecting from the dome. However, a 2021 study found that such a horn was implausible due to the thinness of the outer wall of the dome and the lack of attachment points for a horn on the dome itself, and suggested that the dome (which they proposed was primarily for enhancing the sense of smell) was instead covered by a hard keratinous pad (comparable to the bosses of muskox and African buffalo) and that may have resembled a small horn in mature males.

Elasmotherium is thought to have had a relatively narrow and specialised ecological niche as an inhabitant of the central Eurasian steppe. The high crowned (becoming evergrowing/hypselodont in E. sibiricum, uniquely among rhinoceroses) and complicated enamel pattern of Elasmotherium teeth indicate that they had an abrasive diet of low growing vegetation. Elasmotherium may have fed on grass and/or used its well muscled head to turn over the soil to feed on roots and other subterranean parts of plants.

Elasmotherium has sometimes been claimed to be the basis of the mythical unicorn, though the evidence in support of this hypothesis is highly speculative.

Taxonomy

[edit]

Elasmotherium was first described in 1808-1809 by German/Russian palaeontologist Gotthelf Fischer von Waldheim based on a left lower jaw, four molars, and the tooth root of the third premolar, which was gifted to Moscow University by princess Ekaterina Dashkova in 1807. He first announced the genus name at an 1808 presentation before the Moscow Society of Naturalists, and named the type species E. sibiricum a year later in 1809.[2][3]

The genus name derives from Ancient Greek ἔλασμα (élasma), meaning "metal plate", with the intended meaning "lamina", in reference to the laminated folding of the tooth enamel; and θηρίον (theríon), meaning "beast" and the species name sibericum is probably a reference to the predominantly Siberian origin of Princess Dashkova's collection. However, the specimen's exact origins are unknown. The specimen narrowly escaped destruction by being evacuated to Nizhny Novgorod during the French invasion of Russia in 1812, when most of the rest of Dashkova's collection was destroyed. The specimen was transferred to the Palaeontological Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR (now the Russian Academy of Sciences) in Moscow during the mid-20th century.[3]

Due to the initially limited known remains and the unique morphology of Elasmotherium, for much of the 19th century its affinities to other mammals were the subject of considerable speculation. Fischer suggested in his original description that Elasmotherium was a "pachyderm which finds a place between elephants and rhinoceroses", while others such as Georges Cuvier in 1817, Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest in 1820, and Richard Owen in 1845 saw it as a "missing link" between rhinoceroses and horses, Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville in publications from 1839-1864 suggested that it was an "edentate", and Henri Milne-Edwards in 1868 proposed that it was an aquatic, possibly even marine mammal. Johann Jakob Kaup in 1840-41 was the first author to recognise that Elasmotherium was a rhinoceros, a view followed by Charles Lucien Bonaparte in 1845, who created the group Elasmotheriina to house it. Other authors supporting Elasmotherium as a rhinoceros include George Louis Duvernoy in 1852, who in 1855 erroneously assigned a partial skull correctly attributed to Elasmotherium by Kaup to the new genus and species Stereoceros galli. In 1877, Johann Friedrich von Brandt described the first complete skull of Elasmotherium sibiricum, which put to rest the debate about its affinities and demonstrated unequivocally that Elasmotherium was a rhinoceros.[3][4]24-25 In 1916, a new genus, Enigmatherium and species E. stavropolitanum were named by Pavlova based on a single tooth found in the Northern Caucasus. This species was later recognised as a synonym of E. fischeri, named by Desmarest in 1820, which itself is now considered a synonym of the type species E. sibiricum.[3]

Evolution

[edit]Elasmotherium belongs to the subfamily Elasmotheriinae, distinct from the subfamily which includes all living rhinoceroses, Rhinocerotinae. The depth of the split between Elasmotheriinae and Rhinocerotinae is disputed. Older estimates place the age of divergence around 47 million years ago, during the Eocene,[5] while younger estimates place the split during the Oligocene, around 35-23 million years ago.[6][7] Unambiguous members of Elasmotheriinae first appeared during the Early Miocene, and the subfamily was speciose and widespread across Europe, Africa and Asia during the Miocene epoch.[8]

Cladogram of Rhinocerotidae after Borrani et al. 2025 (note: only a limited selection of elasmothere genera were included in the tree).[9]

| Rhinocerotidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladogram of Elasmotheriina (the subgroup including core members of Elasmotheriinae) after Sun et al. 2023:[10]

| Elasmotheriina |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Elasmotherium is the only known member of Elasmotheriinae to haved survived after the Early Pliocene.[11] with elasmotheriines declining as part of a broader decline of rhinocerotids and many other species of mammals during the late Miocene period.[12] After originating and initially evolving in China (likely from Sinotherium) during the latest Miocene and Pliocene,[13] Elasmotherium migrated westwards into Central Asia and Eastern Europe around 2.6 million years ago, during the earliest part of the Pleistocene epoch.[14][15] Elasmotherium became extinct in China by the end of the Early Pleistocene, around 1 million years ago.[15]

Elasmotherium is the only known member of Elasmotheriinae to haved survived after the Early Pliocene.[11] with elasmotheriines declining as part of a broader decline of rhinocerotids and many other species of mammals during the late Miocene period.[16] After originating and initially evolving in China (likely from Sinotherium) during the latest Miocene and Pliocene,[13] Elasmotherium migrated westwards into Central Asia and Eastern Europe around 2.6 million years ago, during the earliest part of the Pleistocene epoch.[14][15] Elasmotherium became extinct in China by the end of the Early Pleistocene, around 1 million years ago.[15]

Species

[edit]The oldest known species of Elasmotherium is Elasmotherium primigenium from the late Miocene (sometime between around 9 and 5.3 million years ago) of Dingbian County in Shaanxi, China,[13] though some authors have doubted the attribution of this species to Elasmotherium.[17] This species is distinguished from later Elasmotherium species by its more primitive tooth morphology. Like later species, it has the characteristic dome on the skull roof.[13]

There are four largely successive species of Elasmotherium aside from the aforementioned E. primigenium, which are—from oldest to youngest—E. chaprovicum, E. peii, E. caucasicum and E. sibiricum, and which together span from the Late Pliocene to the Late Pleistocene.[18] Elasmotherium species are largely distinguished by differences in their tooth anatomy.[15]

Remains of Elasmotherium from the Khaprovian or Khaprov Faunal Complex, which was at first taken to be E. caucasicum,[19] and then on the basis of the dentition was redefined as a new species, E. chaprovicum (Shvyreva, 2004), named after the Khaprov Faunal Complex.[20] The Khaprov is in the Middle Villafranchian, MN17, which spans the Piacenzian of the Late Pliocene and the Gelasian of the Early Pleistocene of Northern Caucasus, Moldova and Asia and has been dated to 2.6–2.2 Ma.[21] This species is characterised by the relative thickness and roughness of its irregularly folded tooth enamel, its massive metapodial bones, and the morphology of the talus bone of the foot, which are relatively low, have a narrow trochlea and a wide part closest to the (distal) tip of the foot.[15] E. chaprovicum may have existed at the same time as early members of E. peii lived in China.[15]

E. peii was first described by Chow, 1958 for remains found in Shaanxi, China.[22] The species is also known from numerous remains from the classical range of Elasmotherium, and some sources have considered this species to be a synonym of E. caucasicum, but it is currently considered distinct.[18] In the western part of its range, it is mainly found in the Psekups faunal complex between 2.2 and 1.6 Ma.[18] In China, E. peii is considered to be the only Pleistocene species of Elasmotherium, spanning from around 2.6 Ma until at least 1.36 Ma, though its remains in China are rare and only known from a handful of localities.[15] This species is distinguished from other Elasmotherium species by several aspects of its dental anatomy, with the teeth being characterised by early closure of the roots, though the roots remain distinct from the crown of the tooth, and several morphological characters of the teeth, including the persistent presence of a postfossette (a depression of the tooth surface), as well as the shape of the protoloph and metaloph (which are raised areas of teeth).[15]

E. caucasicum was first described by Russian palaeontologist Aleksei Borissiak in 1914. It is placed as part of the Early Pleistocene Tamanian Faunal Unit (1.55–0.8 Ma, named after the Taman Peninsula). E. caucasicum is more primitive than E. sibiricum and likely represents its direct ancestor.[14][15] The teeth of E. caucasicum are distinguished from earlier species by their more complex enamel folding, and from E. sibiricum by having larger teeth and a relatively elongate tooth row.[15] E. caucasicum also differs from the later E. sibiricum in some aspects of its limb bone morphology.[23]

E. sibiricum, described by Johann Fischer von Waldheim in 1808 and chronologically the latest species of the sequence appeared in the Middle Pleistocene, ranging northwards to southern-central Russia, westwards into Ukraine and Moldova in Eastern Europe,[24] eastwards into eastern Kazakhstan and southwards to Uzbekistan in Central Asia, and into Azerbaijan in the Caucasus.[5] This species is distinguished from earlier Elasmotherium by having smaller teeth, a reduced number of premolars, open rooted (evergrowing) molars, as well as very thin and highly complicated enamel folding in the cheek teeth.[15]

Description

[edit]

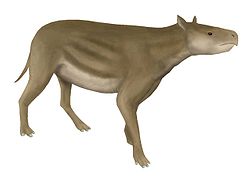

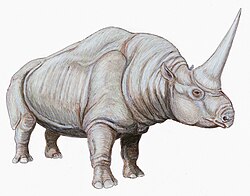

Elasmotherium is the largest known rhinocerotid,[25] and one of the largest members of Rhinocerotoidea, excluding the largest paraceratheres like Paraceratherium.[26]supplementary material The largest known specimens of E. sibiricum reach up to 4.5 m (15 ft) in length, with shoulder heights of over 2 m (6 ft 7 in),[3] with a 2018 study estimating a body mass of around 3.5 tonnes (7,700 lb),[5] while extrapolations based on isolated teeth of E. caucasicum, which are larger than those of E. sibiricum, suggest the largest E. caucasicum individuals may have reached 5–5.2 m (16–17 ft) in body length and a body mass of 4–5 tonnes (8,800–11,000 lb).[3][27] These make Elasmotherium comparable in size to the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) and larger than the contemporary woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis).[28][29]

The cervical vertebrae of the neck were very robust,[3] with the atlas (the first neck vertebra that articulates with the skull) in particular having broad wings up to 70 centimetres (28 in) across, exceeding the width of the skull.[17] The posterior neck vertebrae,[17] as well as the thoracic vertebrae of the back have elongate neural spines, reaching up to 50 centimetres (20 in) in length.[3] The neck of Elasmotherium is thought to have been heavily muscled.[17] Compared to living rhinoceroses, a number of bones of the limbs, including the radius, tibia, astragalus (talus) and metapodials are relatively elongate, though the humerus and ulna are proportionally similar in size to living rhinoceroses.[15] The feet were unguligrade, the front larger than the rear, with three digits at the front and rear, with a vestigial fifth metacarpal.[30]

Elasmotherium is typically reconstructed covered in a considerable layer of fur, generally based on the woolliness exemplified in contemporary megafauna such as woolly mammoths and the woolly rhinoceros. However, it is sometimes depicted as bare-skinned like modern rhinoceroses.[3]

Skull

[edit]

The skulls of E. sibiricum were large and relatively elongate, reaching a length of 86–89 centimetres (34–35 in) in mature male individuals. The skull is less than half as wide at maximum width as it is long. The nasal septum is heavily ossified (bony) rather than cartilaginous.[17] The forward, upper and lower rims of the orbits (eye sockets) are distinctly protuberant, with the back part of the orbit being open. The skull has large areas for the attachment of the neck muscles, including two paired growths on the occipital bone at the back of the skull, which extend further back than the occipital condyles (where the skull articulates with the neck vertebrae).[17]

The most conspicuous feature of the skull of Elasmotherium is the large dome on the top of the frontal bone of the skull roof, generally around 25–35 centimetres (9.8–13.8 in) in diameter. The development of the dome depended on age and sex, being more developed in adult and especially in male individuals. The dome is covered in a rough hummocky texture of uniformly spaced tubercules, though the degree to which this roughness was developed varies considerably between individuals, with some individuals, assume to be female, exhibiting relatively little roughness on the dome. Unlike living rhinoceroses, these tubercules were not arranged into ring-like structures. Along the side of the domes ran sulci grooves, which in life would have supported arterial blood vessels. The interior of the dome was largely hollow, and formed an extension of the nasal cavity, and the sinuses, with the interior of the dome being divided into two halves by the bony nasal septum, with the hollow space being filled with numerous thin walls which would have been covered in mucous membranes, with the outer wall of the dome being relatively thin, varying from 0.5–1.35 centimetres (0.20–0.53 in) thick across the dome.[17]

Elasmotherium sibiricum had two premolars and three molars in each half of both the upper and lower jaws, and lacked any incisors or canines.[3] These teeth were very high crowned (hypsodont), the highest crowned among ungulates, and the molars of E. sibiricum were evergrowing (hypselodont) similar to those of many rodents but uniquely among rhinoceroses (ever growing cheek teeth also evolved in South American notoungulates).[31][17] In E. sibiricum, the teeth completely lacked roots in adult teeth, though some earlier Elasmotherium species had roots in their adult teeth.[17] The cheek teeth exhibit highly complex laminated enamel folding,[3] which is more pronouncedly developed in later species.[15] The roughness of the nasal bone and the interior of the nasal septum suggests that Elasmotherium had a relatively mobile prehensile upper lip.[17]

Cranial ornamentation

[edit]

No preserved soft tissue remains surrounding the dome of Elasmotherium have been found, resulting in a number of different hypotheses regarding its life appearance. Beginning with the first reconstructions of Elasmotherium by Rashevsky under Brant's guidance in 1878, many authors have contended that the dome in Elasmotherium served as the base for a large keratinous horn,[3] often conjectured to be around 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) long.[26]supplementary material This interpretation, while widely popularised in encyclopedias and other works,[3] has not been without its critics, such as Valentin Teryaev in 1948, who argued that a much smaller covering of the dome was present instead.[17]

A 2021 study by Vadim Titov and colleagues supported Teryaev's view, and found that the cranial dome was quite fragile because it was largely hollow, and only had a thin outer wall, and was therefore ill suited for a large horn, and the pattern of the rugosity of the skull did not match the structure found at the base of the horns of living rhinoceroses, and was instead indicative of a smaller cornified (hard) keratinous covering, likely similar to the keratinous bosses present on the heads of muskox (Ovibos moschatus) and African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), that may have resembled a small horn in mature male individuals, which served primarily to protect the fragile dome, and that the dome, as an enlargement of the nasal cavity, primarily functioned to enhance the sense of smell, and possibly secondarily as a resonating chamber for vocalisation in males. They also proposed, based on the roughness of the bone in the area, that the front tip of the snout had another keratinous pad that was used for scraping the ground.[17]

Palaeobiology

[edit]The angle made by the intersection of the plane of the occipital bone with the skull base is around 105–115°, indicating that the head was habitually held low,[17] even lower than the living white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum),[5] which has resulted in it being widely agreed among researchers that Elasmotherium predominantly fed on low-growing vegetation.[17][32]

Valentin Teryaev in 1948 argued that Elasmotherium was a semi-aquatic animal that lived within and in close proximity to water including riverbanks and ponds, feeding on aquatic and nearshore plants with an ecology and physical appearance similar to a hippopotamus. Part of Teryaev's argument was based on the supposed presence of a fourth functional digit in the forefeet of Elasmotherium, similar to tapirs which predominantly inhabit wet environments, but this idea was later shown to be incorrect. Some other authors, while not necessarily agreeing with Teryaev's idea of a semi-aquatic Elasmotherium, have suggested that it predominantly lived near water, such as along river valleys, and foraged on aquatic and semi-aquatic plants.[3][17] However, other researchers have disagreed with this assessment, and argued that Elasmotherium primarily inhabited open terrestrial environments, including steppe, forest steppe and meadows.[17][5] Analysis of carbon and nitrogen isotopes, which resemble those of other steppe dwelling animals, has been argued to support the idea of a steppe-dwelling niche for Elasmotherium.[5] Elasmotherium sibiricum frequently co-occurs with other steppe-dwelling animals in the fossil record, such as the saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica), the extinct large camel Camelus knoblochi, Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus), steppe bison (Bison priscus), and mammoths (Mammuthus chosaricus).[33]

Modern high crowned (hypsodont) hoofed mammals are generally grazers of open environments,[34] with the wrinkled enamel of Elasmotherium teeth suggested to possibly be an adaptation to feeding on tough, fibrous grass.[35] The high crowned teeth of Elasmotherium have either been suggested to an adaptation for feeding on grass or to compensate from the wear caused by the intake of grit on the food it was eating.[5] Dental wear analysis indicates that E. caucasicum and E. sibiricum had a highly abrasive diet, suggested to be the result of a high amount of sandy grit in the soil covering the food they ingested.[17]

The morphology of skull and neck vertebrae suggest that Elasmotherium had the ability to powerfully move its head from side to side (laterally), and combined side to side and upwards motion (dorsolaterally). A number of authors have argued based on multiple lines of evidence, including skull morphology (such as the protuberant eyesocket rims, heavily ossified snout, and enlarged nasal cavity) and carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios (which are highly distinct from those of other rhinoceroses), that Elasmotherium likely heavily fed on roots and other underground parts of plants such as rhizomes, bulbs and tubers, perhaps to an even greater degree than above-ground parts of plants, using their keratinous pad near the front of the snout (rather than the one on the dome), in combination with their powerful neck muscles, to disturb and turn over soil in search of food. Elasmotherium may have moved between different habitats, such as forest, steppe and meadows, seasonally to feed on different plant resources.[17][3]

If the dome functioned as a resonating chamber, it may have been used to amplify loud vocalisations by males, perhaps to attract females and/or to indicate/assert control of territory.[17] Analysis of the limb bones of Elasmotherium suggests that despite its large size, it was probably capable of moving at considerable speed.[5]

At the latest Middle Pleistocene-early Late Pleistocene Irgiz 1 site in European Russia, 7 Elasmotherium sibiricum individuals, ranging from adults to juveniles, appear to have died together in a catastrophic event. Dental microwear analysis, which records an animals diet in their last days/weeks of life, suggests they switched from a low-growing vegetation/grazing diet typical for Elasmotherium (as indicated by their tooth mesowear, which records their long-term diet spanning months to years before death), towards an atypical browsing diet shortly before their death. This may suggest that the Elasmotherium individuals died due to starvation as a result of the ground being covered in an abnormally thick layer of snow, forcing them to attempt to feed on shrubs and other vegetation above the snow layer.[36]

Relationship with humans and extinction

[edit]Elasmotherium sibiricum was previously thought to have gone extinct during the late Middle Pleistocene, around 200,000 years ago as a background extinction, but radiocarbon dates obtained from specimens found in southern European Russia shows its persistence in the region until at least 39,000 and possibly as late as 35,000 years ago, indicating that Elasmotherium survived well into the Last Glacial Period.[5] A claimed later radiocarbon date of around 29,000 years ago from Pavlodar, in northern Kazakhstan is not considered credible.[5] These late dates place Elasmotherium's extinction within the timeframe of the late Quaternary extinction event, when most large terrestrial animals became extinct, generally thought to be the result of climate change, hunting by the globally expanding population of modern humans, or the combination of both. However, there is very little evidence of human interaction with Elasmotherium, and their remains have never been found in any confirmed archaeological context. The last records of Elasmotherium, which date to Marine Isotope Stage 3, correspond to a period of pronounced climatic and environmental change induced by the oscillation between relatively warm interstadial and cool stadial periods, with the last records dating to around the onset of Heinrich stadial 4/Greenland stadial 8, caused by a Heinrich event (a large group of icebergs simultaneously breaking off the North American Laurentide Ice Sheet and travelling into the North Atlantic), corresponding with pronounced cooling, the disruption of grass and herb dominated ecosystems and the spread of the mammoth steppe-tundra across northern Eurasia. The specialised ecology and restricted geographical distribution of Elasmotherium may have contributed to its extinction.[5]

A claimed Late Pleistocene presence in Western Europe, based on a cave painting in Rouffignac Cave in France, which depicts a rhinoceros with a large single horn, has been doubted, because of the complete lack of any Western European remains of Elasmotherium,[4]46-47 and other authors have considered this to be a depiction of the woolly rhinoceros.[3] Other claimed depictions of Elasmotherium have been reported from Shulgan-Tash Cave in the southern Russian Urals, though other authors have considered the claims to be unproven, due to the ambiguous nature of the ochre drawings, and these could again be depictions of the woolly rhinoceros.[3]

Since the 19th century, Elasmotherium has been claimed to be the origin of folkloric creatures, particularly the unicorn, though the evidence in support of this hypothesis is conjectural, and Elasmotherium does not appear to have inhabited the areas where the mythological unicorn is thought to have originated, and the depiction of the unicorn may have been influenced by living rhinoceroses rather than Elasmotherium.[3] As a consequence, E. sibiricum has sometimes been nicknamed the "Siberian Unicorn".[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Elasmotherium". PaleoBiology Database: Basic info. National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis. 2000. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Fischer, G. (1809). "Sur L'Elasmotherium et le Trogontothérium". Mémoires de la Société des naturalistes de Moscou. 2. Moscow: Imprimerie de l'Université Impériale: 250–268.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Zhegallo, V.; Kalandadze, N.; Shapovalov, A.; Bessudnova, Z.; Noskova, N.; Tesakova, E. (2005). "On the fossil rhinoceros Elasmotherium (including the collections of the Russian Academy of Sciences)" (PDF). Cranium. 22 (1): 17–40.

- ^ a b Antoine, P. O. Phylogénie et évolution des Elasmotheriina (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) (Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, 2002). (In French with English abstract)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kosintsev, P.; Mitchell, K. J.; Devièse, T.; van der Plicht, J.; Kuitems, M.; Petrova, E.; Tikhonov, A.; Higham, T.; Comeskey, D.; Turney, C.; Cooper, A.; van Kolfschoten, T.; Stuart, A. J.; Lister, A. M. (2019). "Evolution and extinction of the giant rhinoceros Elasmotherium sibiricum sheds light on late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 31–38. Bibcode:2018NatEE...3...31K. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0722-0. hdl:11370/78889dd1-9d08-40f1-99a4-0e93c72fccf3. PMID 30478308. S2CID 53726338.

- ^ Liu, Shanlin; Westbury, Michael V.; Dussex, Nicolas; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Heintzman, Peter D.; Duchêne, David A.; Kapp, Joshua D.; von Seth, Johanna; Heiniger, Holly; Sánchez-Barreiro, Fátima (August 2021). "Ancient and modern genomes unravel the evolutionary history of the rhinoceros family". Cell. 184 (19): 4874–4885.e16. Bibcode:2021Cell..184.4874L. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.032. hdl:10230/48693. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 34433011. S2CID 237273079.

- ^ Paterson, R. S.; Mackie, M.; Capobianco, A.; Heckeberg, N. S.; Fraser, D.; Demarchi, B.; Munir, F.; Patramanis, I.; Ramos-Madrigal, J.; Liu, S.; Ramsøe, A. D.; Dickinson, M. R.; Baldreki, C.; Gilbert, M.; Sardella, R.; Bellucci, L.; Scorrano, G.; Leonardi, M.; Manica, A.; Racimo, F.; Willerslev, E.; Penkman, K. E. H.; Olsen, J. V.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Rybczynski, N.; Höhna, S.; Cappellini, E. (2025). "Phylogenetically informative proteins from an Early Miocene rhinocerotid". Nature. 643 (8072): 719–724. Bibcode:2025Natur.643..719P. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09231-4. PMC 12267063. PMID 40634620.

- ^ Geraads, Denis; Zouhri, Samir (2021). "A new late Miocene elasmotheriine rhinoceros from Morocco". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 66. doi:10.4202/app.00904.2021.

- ^ Borrani, Antonio; Mackiewicz, Paweł; Kovalchuk, Oleksandr; Barkaszi, Zoltán; Capalbo, Chiara; Dubikovska, Anastasiia; Ratajczak-Skrzatek, Urszula; Sinitsa, Maxim; Stefaniak, Krzysztof; Mazza, Paul P.A. (26 October 2025). "The evolutionary history of Rhinocerotidae: phylogenetic insights, climate influences and conservation implications". Cladistics. doi:10.1111/cla.70015. ISSN 0748-3007. PMID 41139836.

- ^ Sun, Danhui; Deng, Tao; Lu, Xiaokang; Wang, Shiqi (January 2023). "A new elasmothere genus and species from the middle Miocene of Tongxin, Ningxia, China, and its phylogenetic relationship". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 21 (1) 2236619. Bibcode:2023JSPal..2136619S. doi:10.1080/14772019.2023.2236619. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ a b Antoine, Pierre-Olivier; Becker, Damien; Pandolfi, Luca; Geraads, Denis (2025), Melletti, Mario; Talukdar, Bibhab; Balfour, David (eds.), "Evolution and Fossil Record of Old World Rhinocerotidae", Rhinos of the World, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 31–48, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-67169-2_2, ISBN 978-3-031-67168-5, retrieved 1 March 2025

- ^ Stefaniak, Krzysztof; Kovalchuk, Oleksandr; Ratajczak-Skrzatek, Urszula; Kropczyk, Aleksandra; Mackiewicz, Paweł; Kłys, Grzegorz; Krajcarz, Magdalena; Krajcarz, Maciej T.; Nadachowski, Adam; Lipecki, Grzegorz; Karbowski, Karol; Ridush, Bogdan; Sabol, Martin; Płonka, Tomasz (November 2023). "Chronology and distribution of Central and Eastern European Pleistocene rhinoceroses (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) – A review". Quaternary International. 674–675: 87–108. Bibcode:2023QuInt.674...87S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2023.02.004.

- ^ a b c d Sun, Danhui; Deng, Tao; Jiangzuo, Qigao (26 April 2021). "The most primitive Elasmotherium (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) from the Late Miocene of northern China". Historical Biology. 34 (2): 201–211. doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.1907368. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 235558419.

- ^ a b c Schvyreva, A.K. (27 August 2015). "On the importance of the representatives of the genus Elasmotherium (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia) in the biochronology of the Pleistocene of Eastern Europe". Quaternary International. 379: 128–134. Bibcode:2015QuInt.379..128S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.03.052.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Tong, Hao‑wen; Chen, Xi; Zhang, Bei (1 September 2018). "New postcranial bones of Elasmotherium peii from Shanshenmiaozui in Nihewan basin, Northern China". Quaternaire. 29 (3): 195–204. doi:10.4000/quaternaire.10010. ISSN 1142-2904. S2CID 135026963.

- ^ Stefaniak, Krzysztof; Kovalchuk, Oleksandr; Ratajczak-Skrzatek, Urszula; Kropczyk, Aleksandra; Mackiewicz, Paweł; Kłys, Grzegorz; Krajcarz, Magdalena; Krajcarz, Maciej T.; Nadachowski, Adam; Lipecki, Grzegorz; Karbowski, Karol; Ridush, Bogdan; Sabol, Martin; Płonka, Tomasz (November 2023). "Chronology and distribution of Central and Eastern European Pleistocene rhinoceroses (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) – A review". Quaternary International. 674–675: 87–108. Bibcode:2023QuInt.674...87S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2023.02.004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Titov, Vadim V.; Baigusheva, Vera S.; Uchytel', Roman S. (16 November 2021). "The experience in reconstructing of the head of Elasmotherium (Rhinocerotidae)" (PDF). Russian Journal of Theriology. 20 (2): 173–182. doi:10.15298/rusjtheriol.20.2.06. ISSN 1682-3559. S2CID 244138119.

- ^ a b c Schvyreva, A.K. (August 2015). "On the importance of the representatives of the genus Elasmotherium (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia) in the biochronology of the Pleistocene of Eastern Europe". Quaternary International. 379: 128–134. Bibcode:2015QuInt.379..128S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.03.052.

- ^ Logvynenko, Vitaliy (May 2024). "The Development of the Late Pleistocene to Early Middle Pleistocene Large Mammal Fauna of Ukraine" (PDF). 18th International Senckenberg Conference 2004 in Weimar (Abstracts). Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (SGN).

- ^ Titov, V.V. (2008). Late Pliocene large mammals from Northeastern Sea of Azov Region (PDF) (in Russian and English). Rostov-on-Don: SSC RAS Publishing.

- ^ Bajgusheva, Vera S.; Titov, Vadim V. (May 2024). "Results of the Khapry Faunal Unit revision" (PDF). 18th International Senckenberg Conference 2004 in Weimar (Abstracts). Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (SGN).

- ^ Chow, M.C., 1958. New elasmotherine Rhinoceroses from Shansi. Vertebrato PalA-siatica 2, 135-142.

- ^ Deng, T. & Zheng, M. Limb bones of Elasmotherium (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) from Nihewan (Hebei, China). Vert. PalAs. 43, 110–121 (2005).

- ^ Baigusheva, Vera; Titov, Vadim (2010). "Pleistocene Large Mammal Associations of the Sea of Azov and Adjacent Regions". In Titov, V.V.; Tesakov, A.S. (eds.). Quaternary stratigraphy and paleontology of the Southern Russia: connections between Europe, Africa and Asia: Abstracts of the International INQUA-SEQS Conference (Rostov-on-Don, June 21–26, 2010) (PDF). Rostov-on-Don: Russian Academy of Science. pp. 24–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Etienne, Cyril; Mallet, Christophe; Cornette, Raphaël; Houssaye, Alexandra (28 March 2020). "Influence of mass on tarsus shape variation: a morphometrical investigation among Rhinocerotidae (Mammalia: Perissodactyla)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 129 (4): 950–974. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blaa005. ISSN 0024-4066.

- ^ a b Gayford, Joel H.; Engelman, Russell K.; Sternes, Phillip C.; Itano, Wayne M.; Bazzi, Mohamad; Collareta, Alberto; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo; Shimada, Kenshu (September 2024). "Cautionary tales on the use of proxies to estimate body size and form of extinct animals". Ecology and Evolution. 14 (9) e70218. Bibcode:2024EcoEv..1470218G. doi:10.1002/ece3.70218. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 11368419. PMID 39224151.

- ^ Schvyreva, A.K. (2016). Эласмотерии плейстоцена Евразии (PDF) (in Russian). pp. 103–105.

- ^ Cerdeño, Esperanza; Nieto, Manuel (1995). "Changes in Western European Rhinocerotidae related to climatic variations" (PDF). Palaeo. 114 (2–4): 328. Bibcode:1995PPP...114..325C. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(94)00085-M.

- ^ Cerdeño, Esperenza (1998). "Diversity and evolutionary trends of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla)" (PDF). Palaeo. 141 (1–2): 13–34. Bibcode:1998PPP...141...13C. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(98)00003-0.

- ^ Belyaeva, E.I. (1977). "About the Hyroideum, Sternum and Metacarpale V Bones of Elasmotherium sibiricum Fischer (Rhinocerotidae)" (PDF). Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India. 20: 10–15. doi:10.1177/0971102319750103.

- ^ Raia, Pasquale; Carotenuto, Francesco; Meloro, Carlo; Piras, Paolo; Pushkina, Diana (January 2010). "The Shape of Contention: Adaptation, History, and Contingency in Ungulate Mandibles". Evolution. 64 (5): 1489–1903. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00921.x. PMID 20015238.

- ^ van der Made, Jan; Grube, René (2010). "The rhinoceroses from Neumark-Nord and their nutrition". In Meller, Harald (ed.). Elefantenreich – Eine Fossilwelt in Europa (PDF). Halle/Saale. pp. 382–394.

- ^ Klementiev, Alexey M.; Khatsenovich, Arina M.; Tserendagva, Yadmaa; Rybin, Evgeny P.; Bazargur, Dashzeveg; Marchenko, Daria V.; Gunchinsuren, Byambaa; Derevianko, Anatoly P.; Olsen, John W. (14 March 2022). "First Documented Camelus knoblochi Nehring (1901) and Fossil Camelus ferus Przewalski (1878) From Late Pleistocene Archaeological Contexts in Mongolia". Frontiers in Earth Science. 10 861163. Bibcode:2022FrEaS..10.1163K. doi:10.3389/feart.2022.861163. hdl:10150/664436. ISSN 2296-6463.

- ^ Mendoza, M.; Palmqvist, P. (February 2008). "Hypsodonty in ungulates: an adaptation for grass consumption or for foraging in open habitat?". Journal of Zoology. 273 (2): 134–142. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00365.x.

- ^ Sun, Danhui; Deng, Tao; Jiangzuo, Qigao (1 February 2022). "The most primitive Elasmotherium (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) from the Late Miocene of northern China". Historical Biology. 34 (2): 201–211. Bibcode:2022HBio...34..201S. doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.1907368. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ Rivals, Florent; Prilepskaya, Natalya E.; Belyaev, Ruslan I.; Pervushov, Evgeny M. (October 2020). "Dramatic change in the diet of a late Pleistocene Elasmotherium population during its last days of life: Implications for its catastrophic mortality in the Saratov region of Russia". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 556 109898. Bibcode:2020PPP...55609898R. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109898.

Further reading

[edit]- Antoine, Pierre-Olivier (March 2003). "Middle Miocene elasmotheriine Rhinocerotidae from China and Mongolia: taxonomic revision and phylogenetic relationships" (PDF). Zoologica Scripta. 32 (2): 95–118. doi:10.1046/j.1463-6409.2003.00106.x. S2CID 86800130.

- Deng, Tao; Zheng, Min (2005). "Limb Bones of Elasmotherium (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) from Nihewan (Hebei, China)" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica (in Chinese and English) (4): 110–121.

- Hieronymus, Tobin L. (2009). Osteological Correlates of Cephalic Skin Structures in Amniota: Documenting the Evolution of Display and Feeding Structures with Fossil Data (Doctoral Thesis). College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- Russell, James R. (2009). "From Zoroastrian Cosmology and Armenian heresiology to the Russian novel". In Allison, Christine; Joristen-Pruschke, Anke; Wendtland, Antje (eds.). From Daēnā to Dîn: Religion, Kultur und Sprache in der iranischen Welt; Festschrift für Philip Kezenbroek zum 60. Geburstag. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 141–208.

- Sinon, Denis (1960). "Sur les noms altaïque de la licorne" (PDF). Wiener Zeitschrift für der Kunde des Morgenlandes (in French) (56): 168–176.

- Shvyreva, A.K. (2016). Эласмотерии плейстоцена Евразии (in Russian). Печатный Двор, Ставрополь.