Draft:Planet copy

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take more than six months, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 94 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

| ||||

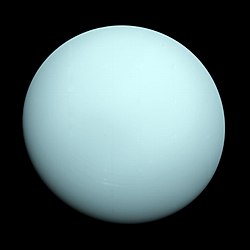

The eight planets of the Solar System

Shown in order from the Sun and in true color. Sizes are not to scale. |

A planet is an astronomical body orbiting a star or stellar remnant that

- is massive enough to be rounded by its own gravity,

- is not massive enough to cause thermonuclear fusion, and

- has cleared its neighbouring region of planetesimals.[lower-alpha 1][1][2]

The term planet is ancient, with ties to history, astrology, science, mythology, and religion. Several planets in the Solar System can be seen with the naked eye. These were regarded by many early cultures as divine, or as emissaries of deities. As scientific knowledge advanced, human perception of the planets changed, incorporating a number of disparate objects. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) officially adopted a resolution defining planets within the Solar System. This definition is controversial because it excludes many objects of planetary mass based on where or what they orbit. Although eight of the planetary bodies discovered before 1950 remain "planets" under the modern definition, some celestial bodies, such as Ceres, Pallas, Juno and Vesta (each an object in the solar asteroid belt), and Pluto (the first trans-Neptunian object discovered), that were once considered planets by the scientific community, are no longer viewed as such. Added some edits - 123.

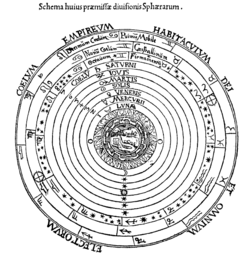

The planets were thought by Ptolemy to orbit Earth in deferent and epicycle motions. Although the idea that the planets orbited the Sun had been suggested many times, it was not until the 17th century that this view was supported by evidence from the first telescopic astronomical observations, performed by Galileo Galilei. At about the same time, by careful analysis of pre-telescopic observation data collected by Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler found the planets' orbits were not circular but elliptical. As observational tools improved, astronomers saw that, like Earth, the planets rotated around tilted axes, and some shared such features as ice caps and seasons. Since the dawn of the Space Age, close observation by space probes has found that Earth and the other planets share characteristics such as volcanism, hurricanes, tectonics, and even hydrology.

Planets are generally divided into two main types: large low-density giant planets, and smaller rocky terrestrials. Under IAU definitions, there are eight planets in the Solar System. In order of increasing distance from the Sun, they are the four terrestrials, Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, then the four giant planets, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Six of the planets are orbited by one or more natural satellites.

Several thousands of planets around other stars ("extrasolar planets" or "exoplanets") have been discovered in the Milky Way. As of 1 October 2017, 3,671 known extrasolar planets in 2,751 planetary systems (including 616 multiple planetary systems), ranging in size from just above the size of the Moon to gas giants about twice as large as Jupiter have been discovered, out of which more than 100 planets are the same size as Earth, nine of which are at the same relative distance from their star as Earth from the Sun, i.e. in the habitable zone.[3][4] On December 20, 2011, the Kepler Space Telescope team reported the discovery of the first Earth-sized extrasolar planets, Kepler-20e[5] and Kepler-20f,[6] orbiting a Sun-like star, Kepler-20.[7][8][9] A 2012 study, analyzing gravitational microlensing data, estimates an average of at least 1.6 bound planets for every star in the Milky Way.[10] Around one in five Sun-like[lower-alpha 2] stars is thought to have an Earth-sized[lower-alpha 3] planet in its habitable[lower-alpha 4] zone.

History

[edit]

The idea of planets has evolved over its history, from the divine lights of antiquity to the earthly objects of the scientific age. The concept has expanded to include worlds not only in the Solar System, but in hundreds of other extrasolar systems. The ambiguities inherent in defining planets have led to much scientific controversy.

The five classical planets, being visible to the naked eye, have been known since ancient times and have had a significant impact on mythology, religious cosmology, and ancient astronomy. In ancient times, astronomers noted how certain lights moved across the sky, as opposed to the "fixed stars", which maintained a constant relative position in the sky.[11] Ancient Greeks called these lights πλάνητες ἀστέρεςCategory:Articles containing Ancient Greek-language text (planētes asteres, "wandering stars") or simply πλανῆταιCategory:Articles containing Ancient Greek-language text (planētai, "wanderers"),[12] from which today's word "planet" was derived.[13][14][15] In ancient Greece, China, Babylon, and indeed all pre-modern civilizations,[16][17] it was almost universally believed that Earth was the center of the Universe and that all the "planets" circled Earth. The reasons for this perception were that stars and planets appeared to revolve around Earth each day[18] and the apparently common-sense perceptions that Earth was solid and stable and that it was not moving but at rest.

Babylon

[edit]The first civilization known to have a functional theory of the planets were the Babylonians, who lived in Mesopotamia in the first and second millennia BC. The oldest surviving planetary astronomical text is the Babylonian Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa, a 7th-century BC copy of a list of observations of the motions of the planet Venus, that probably dates as early as the second millennium BC.[19] The MUL.APIN is a pair of cuneiform tablets dating from the 7th century BC that lays out the motions of the Sun, Moon, and planets over the course of the year.[20] The Babylonian astrologers also laid the foundations of what would eventually become Western astrology.[21] The Enuma anu enlil, written during the Neo-Assyrian period in the 7th century BC,[22] comprises a list of omens and their relationships with various celestial phenomena including the motions of the planets.[23][24] Venus, Mercury, and the outer planets Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn were all identified by Babylonian astronomers. These would remain the only known planets until the invention of the telescope in early modern times.[25]

- ^ This definition is drawn from two separate IAU declarations; a formal definition agreed by the IAU in 2006, and an informal working definition established by the IAU in 2001/2003 for objects outside of the Solar System. The official 2006 definition applies only to the Solar System, whereas the 2003 definition applies to planets around other stars. The extrasolar planet issue was deemed too complex to resolve at the 2006 IAU conference.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

1in5sunlikewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

1in5earthsizedwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

1in5habitablewas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

- ^ "IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes". International Astronomical Union. 2006. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ^ "Working Group on Extrasolar Planets (WGESP) of the International Astronomical Union". IAU. 2001. Archived from the original on 2006-09-16. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "NASA discovery doubles the number of known planets". USA TODAY. 10 May 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Schneider, Jean (16 January 2013). "Interactive Extra-solar Planets Catalog". The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2013-01-15.

- ^ NASA Staff (20 December 2011). "Kepler: A Search For Habitable Planets – Kepler-20e". NASA. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ^ NASA Staff (20 December 2011). "Kepler: A Search For Habitable Planets – Kepler-20f". NASA. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ^ Johnson, Michele (20 December 2011). "NASA Discovers First Earth-size Planets Beyond Our Solar System". NASA. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ^ Hand, Eric (20 December 2011). "Kepler discovers first Earth-sized exoplanets". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2011.9688.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis. "Two Earth-Size Planets Are Discovered", New York Times, 20 December 2011. Retrieved on 2011-12-21.

- ^ Cassan, Arnaud; D. Kubas; J.-P. Beaulieu; M. Dominik; et al. (12 January 2012). "One or more bound planets per Milky Way star from microlensing observations". Nature. 481 (7380): 167–169. arXiv:1202.0903. Bibcode:2012Natur.481..167C. doi:10.1038/nature10684. PMID 22237108. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author26=(help) - ^ "Ancient Greek Astronomy and Cosmology". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2016-05-19.

- ^ πλανήτης, H. G. Liddell and R. Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, ninth edition, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940).

- ^ "Definition of planet". Merriam-Webster OnLine. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ "Planet Etymology". dictionary.com. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

oedwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Neugebauer, Otto E. (1945). "The History of Ancient Astronomy Problems and Methods". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 4 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1086/370729.

- ^ Ronan, Colin. "Astronomy Before the Telescope". Astronomy in China, Korea and Japan (Walker ed.). pp. 264–265.

- ^ Kuhn, Thomas S. (1957). The Copernican Revolution. Harvard University Press. pp. 5–20. ISBN 0-674-17103-9.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

practicewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Francesca Rochberg (2000). "Astronomy and Calendars in Ancient Mesopotamia". In Jack Sasson (ed.). Civilizations of the Ancient Near East. Vol. III. p. 1930.

- ^ Holden, James Herschel (1996). A History of Horoscopic Astrology. AFA. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-86690-463-6.

- ^ Hermann Hunger, ed. (1992). Astrological reports to Assyrian kings. State Archives of Assyria. Vol. 8. Helsinki University Press. ISBN 951-570-130-9.

- ^ Lambert, W. G.; Reiner, Erica (1987). "Babylonian Planetary Omens. Part One. Enuma Anu Enlil, Tablet 63: The Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 107 (1): 93–96. doi:10.2307/602955. JSTOR 602955.

- ^ Kasak, Enn; Veede, Raul (2001). Mare Kõiva; Andres Kuperjanov (eds.). "Understanding Planets in Ancient Mesopotamia" (PDF). Electronic Journal of Folklore. 16. Estonian Literary Museum: 7–35. doi:10.7592/fejf2001.16.planets. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ A. Sachs (May 2, 1974). "Babylonian Observational Astronomy". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 276 (1257). Royal Society of London: 43–50 [45 & 48–9]. Bibcode:1974RSPTA.276...43S. doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0008. JSTOR 74273.