Birth Control Review

| |

| Founder | Margaret Sanger |

|---|---|

| Publisher | New York Woman's Publishing Company |

| Editor-in-chief | Margaret Sanger |

| Associate editor | Annie Porritt |

| Founded | 1917 |

| Ceased publication | 1940 |

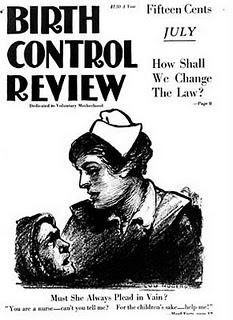

Birth Control Review, sometimes styled The Birth Control Review, was an American lay magazine established and edited by Margaret Sanger in 1917, three years after her friend, Otto Bobsein, coined the term "birth control" to describe voluntary motherhood or the ability of a woman to space children "in keeping with a family's financial and health resources."[1] It continued publication until 1940.

History

[edit]

The predecessor to the Birth Control Review was Sanger's previous publication titled "The Woman Rebel", a seven-issue periodical running March—October 1914.[2] This journal was the first to publish the term "birth control" in print. This would subsequently lead to Sanger's use of the term to mobilize the Birth Control movement of the 20th century.

In October 1916, Sanger opened a family planning and birth control clinic in Brownsville, Brooklyn, New York.[3] Sanger published the first issue while imprisoned with Ethel Byrne, her sister, and Fannie Mindell for giving contraceptives and instruction to poor women at the Brownsville Clinic in New York.[4][5] The first edition of the journal came out officially in February 1917.[6] Frederick A. Blossom distributed copies of this first issue as early as January 29, 1917 at a meeting at Carnegie Hall.[7] The journal originally sold for fifteen cents a copy with a one dollar a year subscription.[6] Original editors included Sanger and Blossom.[6] Elizabeth Stuyvesant served as the secretary-treasurer.[6]

During the first year of publication, the Review was funded through sales, subscriptions and donations.[8] While Sanger was in prison, Blossom spent the money for the Review and then resigned.[6] Issues continued in 1917 until June when there was a pause in publication due to lack of funds, though it was publicly attributed to the US entry into World War I.[6] A December 1917 edition came out and one salesperson, Kitty Marion, helped sell over 1,000 copies in New York. [9] Her sales helped keep the Review afloat.[9] When Marion was selling copies of the magazine, she endured heckling, abuse, death threats and police obstruction.[10]

Sanger worked with Jessie Ashley, Juliet Ruhblee and Helen M. Todd to create the New York Woman's Publishing Company which became the official publisher of the Review starting in May 1918.[9][11] Mary Knoblauch was the managing editor.[11]

After 1921, the American Birth Control League (ABCL) took over publication of the journal.[12] Annie Porritt became an associate editor of the journal in 1922.[13] Sanger remained editor-in-chief until January 31, 1929, when she turned it over to the ABCL.[8][1]

Between 1933 and 1940, the Review became a shorter "monthly bulletin."[8] The last issue was published in January 1940.[14][15]

Content

[edit]

The main goal of the Review was to increase public support for birth control by using both academic and popular arguments to build support for birth control practices both legally and socially.[16] The BCR urged its readers join groups such as American Birth Control League (which spanned 10 different branches and later became Planned Parenthood). Content included news of birth control activities, articles by scholars, activists, and writers on birth control, and reviews of books and other publications.[17] The Review also included art and fiction in the form of cartoons, poetry and short stories.[17] The journal published statistics about the effectiveness of contraceptives.[18] Information on diseases, especially sexually transmitted infections and tuberculosis, were published.[8] It also included case studies and first hand accounts from women.[8]

Some editions published a column called "Ten Good Reasons for Birth Control."[12] Sanger herself contributed many editorials and articles for the journal.[19] Her speeches were also published.[8] Other contributors included Havelock Ellis, who wrote about psychology and sexual wellness.[19] and Mary Dennett, who argued for birth control as a civil liberty.[20] Eugenicists such as Roswell Johnson, David Starr Jordan, Sigard Adolphus Knopf, C. C. Little, Paul Popenoe, William J. Robinson and Lothrop Stoddard wrote for the magazine.[21][9][15] Eugene V. Debs and Olive Schreiner both contributed to the Review.[21]

Black authors also contributed to the Review. Special editions included information for and by Black people relating to family planning.[22] Angelina Weld Grimké wrote two short stories for the Review.[23] Other contributing writers included Midian Othello Bousfield, Elmer A. Carter, W. E. B. Du Bois, Isaac Fisher, Charles S. Johnson, Chandler Owen, and George Schuyler.[24][25]

Circulation

[edit]The Comstock Act of 1873 made mailing information about birth control and contraceptives, as well as any "article, instrument, substance, drug, medicine, or thing" intended for birth control or abortion, illegal.[26] By 1919, most states also had laws that somehow condemned distributing or promoting contraceptives.[27]

In the May 1918 issue, the editorial staff stated that the U.S. Postal Service had allowed the Review to have "second-class" mailing privileges.[6] The journal was available in almost every state and circulation was at 10,000 copies an issue by 1922.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Lagerway, Mary D. (1999). "Nursing, social contexts, and ideologies in the early United States birth control movement". Nursing Inquiry. 6 (4): 250–258. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1800.1999.00037.x. PMID 10696211.

- ^ "Electronic Samples from The Margaret Sanger Papers Project". modeleditions.blackmesatech.com. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ "Birth Control Organizations - Brownsville Clinic and Committee of 100 History". The Margaret Sanger Papers Project. Retrieved September 24, 2025.

- ^ "Mrs. Sanger defies courts before 3,000". The New York Times. January 30, 1917. p. 4.

- ^ "League backs up "Birth Control"". The Washington Post. February 12, 1917. p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Murphree & Gower 2013, p. 216.

- ^ Kennedy 1979, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d e f g Engs, Ruth C. (2003). The Progressive Era's Health Reform Movement: A Historical Dictionary. ABC-CLIO. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-313-05185-2.

- ^ a b c d Engelman 2011, p. 99.

- ^ Engelman 2011, p. 101.

- ^ a b Murphree & Gower 2013, p. 217.

- ^ a b "The Birth Control Review, 1928-1929". University of Southern Mississippi. Retrieved September 24, 2025.

- ^ "Her Paper Causes Growing Comment". Hartford Courant. October 10, 1922. p. 18. Retrieved September 24, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Margaret Sanger Papers Project". New York University. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ a b Bullough, Vern L. (2002). Encyclopedia of Birth Control. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-57607-533-3.

- ^ Murphree & Gower 2013, p. 212.

- ^ a b Murphree & Gower 2013, p. 219.

- ^ McCann 1994, p. 30.

- ^ a b Murphree & Gower 2013, p. 218.

- ^ Siegel & Ziegler 2025, p. 1068.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1979, p. 89.

- ^ McCann 1994, p. 139.

- ^ Wheeler 2015, p. 179.

- ^ Vincent-Smoot, Ferol (June 18, 1932). "Magazine Devote Issue to Negroes and Birth Control". New Journal and Guide. p. 27. Retrieved September 25, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wheeler 2015, p. 182.

- ^ Murphree & Gower 2013, p. 214.

- ^ Ruppenthal, J. C. (December 22, 2017). "Criminal Statutes on Birth Control". Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2025.

Sources

[edit]- Engelman, Peter (2011). A History of the Birth Control Movement in America. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36510-2.

- Kennedy, David M. (1979). Birth Control in America: The Career of Margaret Sanger. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-01495-2.

- McCann, Carole R. (1994). Birth Control Politics in the United States, 1916-1945. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801424909 – via Internet Archive.

- Murphree, Vanessa; Gower, Karla K. (June 2013). "'Making Birth Control Respectable': The Birth Control Review, 1917-1928". American Journalism. 30 (2): 210–234. doi:10.1080/08821127.2013.788464 – via Taylor & Francis.

- Siegel, Reva B.; Ziegler, Mary (February 2025). "Comstockery: How Government Censorship Gave Birth to the Law of Sexual and Reproductive Freedom, and May Again Threaten It". Yale Law Journal. 134 (4): 1068–1181 – via EBSCOhost.

- Wheeler, Raven L. (July 2015). "The Queer Collaboration: Angelina Weld Grimké and the Birth Control Movement". Critical Insights: LGBTQ Literature: 179–192 – via EBSCOhost.

External links

[edit]- "First issue". Birth Control Review. 1 (1). February 1917.

- Sanger, Margaret. "Birth Control Review Digital Archives". Birth Control Review: 24 volumes.

- Birth Control Review History

Further reading

[edit]- Rachel Schreiber. “’Breed!’: the graphic satire of the Birth Control Review, in eds. Tormey and Whiteley, Art, Politics and the Pamphleteer (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 256-273.

- Lifestyle magazines published in the United States

- Defunct women's magazines published in the United States

- Defunct English-language magazines

- Defunct health magazines published in the United States

- Magazines established in 1917

- Magazines disestablished in 1940

- Defunct magazines published in New York (state)

- Parenting magazines

- Defunct feminist magazines published in the United States

- Eugenics in the United States

- Birth control in the United States

- Margaret Sanger