Fugitive slaves in the United States

Fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were historical terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe individuals who fled the institution of slavery in the United States. Modern historical scholarship often prefers the terms self-emancipated people or freedom seekers to acknowledge the active role these individuals took in claiming their own liberty.

The history of self-emancipation is linked to two federal laws that established the right of retrieval: the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The legal status of a person escaping slavery was initially addressed in the United States Constitution's Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3), which mandated the return of such individuals to the party claiming ownership. This legal framework, in tension with resistance efforts like the Underground Railroad and Northern "personal liberty laws," intensified the sectional conflict between slaveholding states and free states, contributing significantly to the causes of the American Civil War.

Generally, freedom seekers tried to reach states or territories where slavery was banned, including Canada, or, until 1821, Spanish Florida. Most slave laws tried to control slave travel by requiring them to carry official passes if traveling without an enslaver.

Passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increased penalties against runaway slaves and those who aided them. Because of this, some freedom seekers left the United States altogether, traveling to Canada or Mexico. Approximately 100,000 enslaved Americans escaped to freedom.[1][2]

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

Constitutional and legal origins

[edit]- Northwest Ordinance (1787)

- Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions (1798–99)

- End of Atlantic slave trade

- Missouri Compromise (1820)

- Tariff of Abominations (1828)

- Nat Turner's Rebellion (1831)

- Nullification crisis (1832–33)

- Abolition of slavery in the British Empire (1834)

- Texas Revolution (1835–36)

- United States v. Crandall (1836)

- Gag rule (1836–44)

- Commonwealth v. Aves (1836)

- Murder of Elijah Lovejoy (1837)

- Burning of Pennsylvania Hall (1838)

- American Slavery As It Is (1839)

- United States v. The Amistad (1841)

- Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842)

- Texas annexation (1845)

- Mexican–American War (1846–48)

- Wilmot Proviso (1846)

- Nashville Convention (1850)

- Compromise of 1850

- Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852)

- Recapture of Anthony Burns (1854)

- Kansas–Nebraska Act (1854)

- Ostend Manifesto (1854)

- Bleeding Kansas (1854–61)

- Caning of Charles Sumner (1856)

- Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

- The Impending Crisis of the South (1857)

- Panic of 1857

- Lincoln–Douglas debates (1858)

- Oberlin–Wellington Rescue (1858)

- John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry (1859)

- Virginia v. John Brown (1859)

- 1860 presidential election

- Crittenden Compromise (1860)

- Secession of Southern states (1860–61)

- Peace Conference of 1861

- Corwin Amendment (1861)

- Battle of Fort Sumter (1861)

Colonial precedents

[edit]Before the U.S. Constitution was ratified, agreements existed among the colonies for the mutual return of those who had escaped bondage. The New England Articles of Confederation of 1643 contained a clause providing for the return of fugitive slaves from one member colony to another. These early agreements established a legal framework for the recovery of human property, foreshadowing the federal mechanisms that would follow.

Over time, the states began to divide into slave states and free states. Maryland and Virginia passed laws to reward people who captured and returned enslaved people to their enslavers. Slavery was abolished in five states by the time of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. At that time, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island had become free states.

The Fugitive Slave Clause (1787)

[edit]During the Constitutional Convention, Southern delegates expressed concern that states that had abolished slavery would obstruct the recovery of runaways. Although the Constitution was ratified in 1788 without using the words "slave" or "slavery," it recognized the institution through the Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3). It stated:

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

This provision guaranteed a slaveholder's right to repossess their "property" and barred free states from legally emancipating a person who escaped from a slave state. The Constitution also recognized the institution via the three-fifths clause and the prohibition on banning the importation of slaves prior to 1808 (Article I, Section 9).[3]

Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

[edit]Because the constitutional clause lacked a federal enforcement procedure, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. This federal law permitted slaveholders or their designated agents to seize an alleged fugitive in any state and bring them before a magistrate. The law required minimal proof—often just an affidavit or oral testimony—to establish ownership. Crucially, it afforded the accused no right to a jury trial.

The Act allowed for fines of $500 (equivalent to $11,755 in 2024) for individuals who assisted slaves in their escape. Slave hunters were obligated to obtain a court-approved affidavit in order to apprehend an enslaved individual, giving rise to the formation of an intricate network of safe houses commonly known as the Underground Railroad.[4]

This low burden of proof made the law a danger to free Black citizens, who were frequently kidnapped and sold into slavery. A famous example of the law's limitations in practice was the case of Oney Judge, who self-emancipated from George Washington's household and successfully avoided multiple recapture attempts.

Self-emancipation and resistance (1793–1850)

[edit]Demographics

[edit]Analysis of fugitive slave advertisements placed by slaveholders reveals that self-emancipation was frequently a calculated act of resistance rather than a random impulse. Advertisements often detailed the gender, age, skills (such as literacy), and family ties of the escapees. Historical analysis suggests that men under the age of 35 comprised the majority of those who attempted and succeeded in escaping long distances.[5]

Escape methods and destinations

[edit]

Self-emancipation involved various methods of flight. While many freedom seekers followed the organized network of the Underground Railroad toward Northern free states, Canada, or Mexico, scholarly research indicates that the majority of runaways remained within the slaveholding South.[6]

To throw tracking dogs off the trail, escaped slaves often rubbed turpentine on their shoes or scattered "soil from a graveyard" on their tracks.[7] Another technique for scent masking was the use of wild onions or other pungent weeds.[8]

- Urban Hiding: In the Upper South, people who escaped slavery often successfully camouflaged themselves within large urban free Black populations in cities such as Baltimore and Richmond, becoming "illegal self-emancipators."[6] Some "passed" as free persons, living for extended periods outside of their enslaver's control. In one documented case in Baton Rouge, a man was discovered living in the steeple of a local church, equipped with "kitchen furniture, extra clothes, dried beef, a revolver, and a knife."[9]

- International Asylums: Until 1821, Spanish Florida provided asylum. After 1834, the British Bahamas also served as a refuge where British law ensured freedom.

- Canada: Following the tightening of U.S. laws in 1850, Canada became the primary destination for those seeking permanent safety, as slavery had been abolished there by 1834.

Maroon communities

[edit]Some fugitives established Maroon communities—independent settlements in geographically isolated regions, sometimes integrating with Native American populations.

- Great Dismal Swamp: Located on the border of Virginia and North Carolina, this swamp sheltered thousands of fugitives who lived independently for decades.

- Black Seminoles: In Florida, fugitive slaves integrated with the Seminole people, forming communities that fought alongside them to resist U.S. expansion.

The Underground Railroad

[edit]| External image | |

|---|---|

The Underground Railroad was a clandestine network of abolitionists who helped fugitive slaves escape to freedom. Members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), African Methodist Episcopal Church, Baptists, Methodists, and other religious sects helped in operating the network.[10][11] The network used railway terminology ("stations", "conductors") and extended throughout the United States into Canada.

Hiding places called "stations" were set up in private homes, churches, and schoolhouses in border states between slave and free states. John Brown had a secret room in his tannery to give escaped enslaved people places to stay on their way.[12]

Harriet Tubman

[edit]

One of the most notable conductors was Harriet Tubman. Born into slavery in Dorchester County, Maryland, around 1822, Tubman escaped in 1849. Between 1850 and 1860, she returned to the South numerous times to lead parties of other enslaved people to freedom. She aided hundreds of people, including her parents, in their escape.[13] Tubman wore disguises and sang songs in different tempos, such as Go Down Moses, to indicate whether it was safe for freedom seekers to come out of hiding.[14]

Notable people

[edit]Notable people who gained or assisted others in gaining freedom via the Underground Railroad include:

- Henry "Box" Brown

- John Brown

- Owen Brown

- Elizabeth Margaret Chandler

- Levi Coffin

- Frederick Douglass

- Calvin Fairbank

- Thomas Garrett

- Shields Green

- Laura Smith Haviland

- Lewis Hayden

- Josiah Henson

- Isaac Hopper

- Roger Hooker Leavitt

- Samuel J. May

- Dangerfield Newby

- John Parker

- John Wesley Posey

- John Rankin

- Alexander Milton Ross

- David Ruggles

- Samuel Seawell

- James Lindsay Smith

- William Still

- Sojourner Truth

- Charles Augustus Wheaton

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

[edit]The new law

[edit]Passed as part of the Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was a far stronger measure intended to enforce federal power in recovering self-emancipated people. Key provisions included:

- Compelling federal officials and citizens in free states to assist in captures.

- Denying the accused rights to a jury trial, habeas corpus, or self-testimony.

- A biased fee structure where commissioners received $10 for ruling a person was a fugitive, but only $5 for ruling they were free.

- Severe penalties ($1,000 fine and imprisonment) for aiding freedom seekers.

Capture and punishment

[edit]

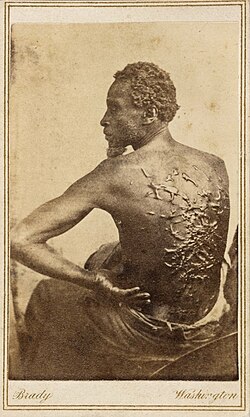

Enslavers were outraged when an enslaved person was found missing. Under the 1850 Act, they could send federal marshals into free states to kidnap them. The law also brought bounty hunters into the business; in 1851, there was a case of a black coffeehouse waiter whom federal marshals kidnapped on behalf of John Debree, who claimed to be the man's enslaver.[15] Enslavers often harshly punished those they successfully recaptured, such as by amputating limbs, whipping, branding, and hobbling.[16]

Northern backlash and personal liberty laws

[edit]The 1850 Act radicalized the abolitionist movement. High-profile cases, such as the 1848 escape of William and Ellen Craft, were framed as continuing the "unfinished American Revolution."[17]

In response, Northern states enacted personal liberty laws. These state laws forbade state officials from assisting in captures and guaranteed fugitives state-level judicial protections. Opponents of the 1850 Act used the Fourth Amendment to argue that seizure procedures violated protections against unwarranted arrest and search.[18]

Conflict and judicial rulings

[edit]The tension between state resistance and federal enforcement led to violence and legal battles.

- Violent Resistance: Notable incidents included the Christiana Resistance (1851), the rescue of Shadrach Minkins (1851), and the Anthony Burns case (1854), which required massive federal intervention to return Burns to Virginia.

- Supreme Court Rulings: In Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), the Supreme Court affirmed federal primacy in enforcing the Fugitive Slave Clause. Later, in Ableman v. Booth (1859), the Court directly challenged Northern resistance by affirming the supremacy of the federal Acts.

Repeal and legacy

[edit]Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Acts largely ceased once the Civil War began, as thousands of self-emancipated people sought refuge with advancing Union lines, where they were often classified as "contraband of war." Congress formally repealed the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850 on June 28, 1864.

The legal basis for these laws was permanently nullified by the Thirteenth Amendment (1865), which abolished slavery. The decades of legal and violent conflict surrounding the recovery of freedom seekers were a significant factor that pushed the country toward civil war.

Communities

[edit]Colonial America

United States

Civil War

- Camp Greene (Washington, D.C.) - Civil war camp

- Theodore Roosevelt Island - Civil war camp

Canada

- Africville - Nova Scotia

- Birchtown - Nova Scotia

- Dawn settlement - Ontario

- Elgin settlement - Ontario

- Fort Malden - Ontario

- Queen's Bush - Ontario

Mexico

- Mascogos - El Nacimiento in Múzquiz Municipality

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Renford, Reese (2011). "Canada; The Promised Land for Slaves". Western Journal of Black Studies. 35 (3): 208–217.

- ^ Mitchell, Mary Niall; Rothman, Joshua D.; Baptist, Edward E.; Holden, Vanessa; Jeffries, Hasan Kwame (2019-02-20). "Rediscovering the lives of the enslaved people who freed themselves". Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- ^ "Article I, Section 9, Constitution Annotated". Congress.gov, Library of Congress. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ "Fugitive Slave Acts". History.com. February 11, 2008. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ "Fugitive slave". Encyclopædia Britannica. October 2025.

- ^ a b Müller, Viola Franziska (2025). "Illegal Self-Emancipation in the Urban Upper South, 1800-1860". OpenEdition Journals.

- ^ "Image 238 of Federal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 4, Georgia, Part 2, Garey-Jones". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2024-07-24.

- ^ "The Realities of Slavery: To the Editor of the N.Y. Tribune". New-York Tribune. 1863-12-03. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-07-24.

- ^ Tregle, Joseph G. (Winter 1981). "Andrew Jackson and the Continuing Battle of New Orleans". Journal of the Early Republic. 1 (4): 373–393. doi:10.2307/3122827. JSTOR 3122827.

- ^ "Underground Railroad". HISTORY. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ IHB (2020-12-15). "The Underground Railroad". IHB. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ Miller, Ernest C. (1948). "John Brown's Ten Years in Northwestern Pennsylvania". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 15 (1): 24–33. ISSN 0031-4528. JSTOR 27766856.

- ^ "Harriet Tubman". Biography. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ "Myths & Facts about Harriet Tubman" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ Schwarz, Frederic D. American Heritage, February/March 2001, Vol. 52 Issue 1, p. 96

- ^ Bland, Lecater (200). Voices of the Fugitives: Runaway Slave Stories and Their Fictions of Self Creation Greenwood Press, [ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Barker, Gordon S. (2018). Fugitive Slaves and the Unfinished American Revolution: Eight Cases, 1848–1856. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780786466856.

- ^ Mannheimer, Michael J. Zydney (2022). "Fugitives from Slavery and the Lost History of the Fourth Amendment". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 170 (3).

Sources

[edit]- Baker, H. Robert (November 2012). "The Fugitive Slave Clause and the Antebellum Constitution". Law and History Review. 30 (4): 1133–1174. doi:10.1017/S0738248012000697. ISSN 0738-2480. JSTOR 23489468. S2CID 145241006.