M. G. Ramachandran

M. G. Ramachandran | |

|---|---|

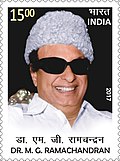

Portrait of M.G.R. from a 2017 commemorative stamp | |

| Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu | |

| In office 9 June 1980 – 24 December 1987 | |

| Governor | |

| Cabinet | |

| Preceded by | President's rule |

| Succeeded by | V. N. Janaki Ramachandran[a] |

| Constituency | |

| In office 30 June 1977 – 17 February 1980 | |

| Governor | Prabhudas B. Patwari |

| Cabinet | Ramachandran I |

| Preceded by | President's rule |

| Succeeded by | President's rule |

| Constituency | Aruppukottai |

| Member of the Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly | |

| In office 24 December 1984 – 24 December 1987 | |

| Chief Minister | Himself |

| Political Party | AIADMK |

| Preceded by | S. S. Rajendran |

| Succeeded by | P. Aasiyan |

| Constituency | Andipatti |

| In office 9 June 1980 – 15 November 1984 | |

| Chief Minister | Himself |

| Political Party | AIADMK |

| Preceded by | T. P. M. Periyaswamy |

| Succeeded by | Pon. Muthuramalingam |

| Constituency | Madurai West |

| In office 30 June 1977 – 17 February 1980 | |

| Chief Minister | Himself |

| Political Party | AIADMK |

| Preceded by | Sowdi Sundara Bharathi |

| Succeeded by | M. Pitchai |

| Constituency | Aruppukottai |

| In office 1 March 1967 – 31 January 1976 | |

| Chief Minister | |

| Political Party | |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | position abolished |

| Constituency | St. Thomas Mount |

| Member of the Tamil Nadu Legislative Council | |

| In office 30 March 1962[1] – 7 July 1964 | |

| Chief Minister | |

| Succeeded by | S. R. P. Ponnuswamy Chettiar |

| General Secretary of the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam | |

| In office 17 October 1986 – 24 December 1987 | |

| Preceded by | S. Raghavanandam |

| Succeeded by | J. Jayalalithaa |

| In office 17 October 1972 – 22 June 1978 | |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | V. R. Nedunchezhiyan |

| Treasurer of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam | |

| In office 27 July 1969 – 10 October 1972 | |

| President | M. Karunanidhi |

| General Secretary | V. R. Nedunchezhiyan |

| Preceded by | M. Karunanidhi |

| Succeeded by | K. Anbazhagan |

| President of the South Indian Artistes' Association | |

| In office 1961–1963 | |

| Preceded by | R. Nagendra Rao |

| Succeeded by | S. S. Rajendran |

| In office 1957–1959 | |

| Preceded by | N. S. Krishnan |

| Succeeded by | Anjali Devi |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Maruthur Gopalan Menon Ramachandran 17 January 1917 |

| Died | 24 December 1987 (aged 70) |

| Cause of death | Cardiac arrest[2] |

| Resting place | M.G.R. and Amma Memorial |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Political party | All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (1972–1987) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Residences | |

| Profession |

|

| Awards |

|

| Nicknames |

|

Maruthur Gopalan Ramachandran (17 January 1917 – 24 December 1987), popularly known by his initials M. G. R., was an Indian politician, director, film producer, film actor and philanthropist, who served as the chief minister of Tamil Nadu from 1977 until his death in 1987. He was the founder and first general secretary of the political party All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK).[3] He is regarded as one of the most influential politicians of post-independent India,[4] and was known by the epithets Makkal Thilagam (Jewel of the People) and Puratchi Thalaivar (Revolutionary Leader).[2] In March 1988, he was posthumously awarded the Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian honour.

Born in British Ceylon in 1917, Ramachandran's family emigrated later to India. In his youth, he became part of a drama troupe to support the family. After a few years of acting in plays, he made his debut in the Tamil film industry with Sathi Leelavathi in 1936. In a career spanning more than five decades, he acted in more than 135 films, majority of them in Tamil.[5] He was regarded as one of the three biggest male actors of Tamil cinema during the period alongside Sivaji Ganesan and Gemini Ganesan.[6] He won the National Film Award for Best Actor in 1971, three Tamil Nadu State Film Awards, and three Filmfare Awards South.

Ramachandran became part of the Indian National Congress in the late 1930s. In 1953, he became a member of the C. N. Annadurai-led Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). He rose through its ranks based on his popularity as a film star. In 1972, three years after Annadurai's death, he left the DMK to establish AIADMK. He steered the AIADMK-led alliance to victory in the 1977 assembly election, defeating the DMK in the process, and was sworn in as the chief minister of Tamil Nadu. Except for a four-month interregnum in 1980, he remained as chief minister until his death in 1987 and led the AIADMK to electoral wins in the 1980 and 1984 elections.[7][8]

In October 1984, Ramachandran was diagnosed with renal failure caused by diabetes, which led to further health problems. Despite undergoing a renal transplant and subsequent treatment at the United States, his condition worsened. He died on 24 December 1987 in his residence in Ramapuram due to a cardiac arrest. On 25 December 1987, his remains were buried at the northern end of the Marina beach, where the MGR Memorial was constructed later. In December 2006, a life-size statue of Ramachandran was unveiled in the Indian Parliament. India Post has released several stamps in his honour, and several establishments and places have been named in his honour including the Chennai Central railway station.

Early life

[edit]Ramachandran was born in Nawalapitiya, Kandy District, British Ceylon (now in Sri Lanka) in a Malayali Nair family to Melakkath Gopalan Menon and Maruthur Satyabhama. His family hailed from Palakkad region in the modern-day Indian state of Kerala.[9][10][11] Ramachandran later claimed himself to be of Tamil Kongu Vellalar descent, whose ancestors had settled in the Kerala region.[12][13][14] His father worked as a magistrate in Kandy, and moved back to India with his family after retirement.[15] He was the youngest of the two sons, and his elder brother was Chakrapani.[15][16] Ramachandran's father died when he was two and a half years old. Soon after the death of his father, his sister also died due to ill health.[16] After his father's death, their relatives did not support the family, and his mother moved to her brother's house in Kumbakonam.[15] His mother worked as a housemaid to put both her sons through school.[16]

During his school days, Ramachandran joined a drama troupe called Boys Company. He trained himself in various aspects, and took on different roles.[16] With help from Kandasamy Mudaliar, he had a brief acting stint overseas in Rangoon and Singapore, where he took up female roles. He returned to India to rejoin Boys Company, and started playing lead roles.[16]

Acting career

[edit]

Ramachandran made his film debut in 1936, in the film Sathi Leelavathi,[17] directed by Ellis R. Dungan, an American-born film director.[18] He followed it with minor appearances and supporting roles in many films.[19] He worked for over a decade in various films before he played his first lead role in Rajakumari, which was commercially successful.[20] Ramachandran later delivered various hit films such as Manthiri Kumari and Maruthanad Elavarasee in 1950.[21][22] He established himself as an action hero in Tamil cinema with Manthiri Kumari (1950) and Marmayogi (1951).[23][24] His popularity rose with the success of En Thangai (1952) and Malaikkallan (1954).[21][25]

Ramachandran's 1955 film Alibabavum 40 Thirudargalum was the Tamil film industry's first-ever full-length gevacolor film.[26] He acted further in commercially successful films such as Madurai Veeran (1956), Chakravarthi Thirumagal and Mahadevi (both released in 1957).[27][28][29] He also directed few films, and his first film as a director and producer was Nadodi Mannan (1958), which became a blockbuster.[30][31] He later starred in Kalai Arasi (1963), which featured a storyline of aliens visiting the earth.[32] The following year, he appeared in Thozhilali and Padagotti.[33][34] After starring in numerous commercially successful films, he held a matinée idol status in Tamil Nadu.[27]

Ramachandran was shot in 1967, which permanently changed his voice.[35] His first film to release after his release from the hospital was Arasakattalai, which had been finished earlier. However, he was shooting for the film Kaavalkaaran, when he was shot, and the film had parts featuring his old and new voices across scenes.[36]

Ramachandran won the Tamil Nadu State Film Award for Best Actor for the film Kudiyirundha Koyil in 1968 and the National Film Award for Best Actor for Rickshawkaran in 1972.[37] His 1973 film Ulagam Sutrum Valiban was one of the first Tamil films to be filmed abroad, and broke the previous box office records of his films.[38] His acting career ended in 1978 with his last film being Madhuraiyai Meetta Sundharapandiyan.[22][39]

Ramachandran remarked there was no question of retirement for anyone associated in whichever capacity with the cine field.[40] Kali N. Rathnam, a pioneer of Tamil stage drama, and K.P. Kesavan were mentors of Ramachandran in his acting career.[41] Ramachandran was often paired with actresses B.Saroja Devi, and J.Jayalalithaa.[42] Jayalalithaa, who later followed him into politics, acted with him in 28 films, with the last film being Pattikaattu Ponnaiya in 1973.[42][43]

Political career

[edit]Early career

[edit]Ramachandran was a member of the Indian National Congress till 1953. In 1953, he joined the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), founded by C. N. Annadurai, and became a prominent member of the party. He became a member of the Madras State Legislative Council in 1962.[44]

1967 assassination attempt

[edit]On 12 January 1967, actor M. R. Radha, who has worked with Ramachandran in various films visited Ramachandran to discuss about a future film project. During the conversation, M. R. Radha stood up and shot Ramachandran near his left ear and then tried to shoot himself.[45] The bullet was lodged behind the first vertebra, and Ramachandran underwent a surgery to remove the bullet. However, a piece of the bullet was left behind as the doctors were apprehensive that it would cause further damage if attempted to be removed.[36]

As a consequence of the surgery, he lost hearing in his left ear and his voice was altered permanently.[46] The bullet piece left behind got dislodged later, and was removed safely, with Ramachandran attributing it to God's grace.[36] He was hospitalised for six weeks and was visited by commoners and people from the film industry, polity and bureaucracy. He conducted his campaign for the 1967 assembly elections from the hospital bed, and was elected to the legislative assembly for the first time.[47][48] Radha was later sentenced to five years in prison for the incident, and died in 1969.[36]

Differences with Karunanidhi and birth of AIADMK

[edit]After the death of his mentor Annadurai, he became the treasurer of the DMK in 1969 after he helped Karunanidhi became the chief minister of the state and president of the party.[49] However, in the early 1970s, the growing popularity of Ramachandran caused a rift with the DMK president and chief minister Karunanidhi. Ramachandran played a key role in the victory of the DMK in the 1971 assembly elections.[50]

Later in the same year, when the DMK government led by Karunanithi wanted to repel the law that was in effect in Tamil Nadu, Ramachandran launched a staunch opposition to it. In 1972, Ramachandran accused that corruption had grown in the DMK after the demise of Annadurai, and demanded the ministers to publicly declare their assets. As a consequence, Ramachandran was expelled from the party temporarily on 10 October 1972, and permanently four days later.[50]

On 17 October 1972, Ramachandran became the leader and general secretary of All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), established by Anakaputhur Ramalingam.[50] He continued to act in films such as Netru Indru Naalai (1974), Idhayakkani (1975), Indru Pol Endrum Vaazhga (1977), and used cinema as a medium to spread his political messages.[5][51]

Chief ministership and continued success

[edit]First elections

[edit]The AIADMK allied with Congress (I) for the 1977 parliamentary election. Though the combine won 34 of the 39 seats in Tamil Nadu, the Janata party won the election and Morarji Desai became the prime minister.[52] The AIADMK contested the 1977 elections, and was part of a four cornered contest against the DMK, the Indian National Congress (Organisation) and the Janata Party. The AIADMK allied itself with the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPM), while Congress (I) and Communist Party of India (CPI) contested as allies.[53][54] The AIADMK-led alliance won the elections by winning 144 seats out of 234 and Ramachandran became the chief minister of Tamil Nadu on 30 June 1977.[55][56]

However, Ramachandran later extended unconditional support to the Janata party government. He continued his support to the Charan Singh-led government in 1979, and Satyavani Muthu and Aravinda Bala Pajanor from the AIADMK became part of the Union Cabinet.[57][58][59]

1980 elections

[edit]

After the fall of the Charan Singh government, fresh parliamentary elections were conducted in 1980. The AIADMK and Janata party alliance won only two seats in the elections, that was won by the DMK-Congress (I) coalition. Following the victory, the AIADMK ministry and the Tamil Nadu assembly dismissed by the central government led by the Congress and fresh elections conducted in 1980.[59] Despite their victory at the 1980 Lok Sabha polls, DMK and Congress failed to win the legislative assembly election. AIADMK won the election and Ramachandran was sworn in as chief minister for the second time.[55][56]

Karunanidhi claimed in April 2009 and in May 2012 that Ramachandran was ready for the merger of his party with the DMK in September 1979, with former Orissa chief minister Biju Patnaik acting as the mediator. The plan failed, because Panruti S. Ramachandran, who was close to Ramachandran acted as a spoiler and Ramachandran changed his mind.[60][61][62]

Later years

[edit]Indira Gandhi was assassinated on 31 October 1984,[63] and was succeeded by her son Rajiv Gandhi, who sought a fresh mandate.[64] Ramachandran-led AIADMK allied with the Congress for the 1984 Indian general election. Despite his poor health, he did contest the assembly election held later that year while still confined to the hospital, winning from Andipatti.[65] During the election, photos of Ramachandran recuperating in hospital were published, creating a sympathy wave among the people.[66] Indira Gandhi's assassination, Ramachandran's appeals from the hospital, and Rajiv Gandhi visits to the state helped create a sympathy wave that helped the alliance sweep both the elections.[67] In the Tamil Nadu assembly, the combine won 195 seats and Ramachandran was later sworn in as the chief minister for the third time.[55][56]

Policies and governance

[edit]Ramachandran was very popular in the state and had high approval from the public.[68][69] He introduced and expanded welfare schemes such as free electricity to farmers, and mid-day meal scheme.[70] The meal scheme for school students, which had been introduced by Kamaraj in 1956, was significantly expanded by Ramachandran in 1980. The scheme was expanded to cover all government and aided schools for all the days of the year including holidays.[71][72] He introduced a free electricity scheme for small and marginal farmers in 1984.[73]

However, as per a study by the Madras Institute of Development Studies in 1988, Ramachandran's tenure did not see a significant upliftment in the economic condition of the poor and the shift of government resources from industrial sector to social welfare schemes contributed to the same.[68]

The decision-making was often centralised during Ramachandran's tenure. While there were criticism regarding the efficiency of such working, supporters of Ramachandran counter that most of these problems were a result of the party members serving Ramachandran rather than the leader himself. His charisma and popularity trumped policy decisions that led to his eventual success during his tenure as chief minister.[74]

Ramachandran allowed the continued sale of liquor, which he opposed when the ban on which was overturned by his predecessor Karunanidhi in 1971. He rescinded the ban on toddy in 1981, and reversed it six years later. He established the Tamil Nadu State Marketing Corporation in 1983 for the import and sale of foreign made liquor.[75]

Natwar Singh in his autobiography One Life is Not Enough alleged that Ramachandran covertly supported the cause of independent Tamil Eelam and financed the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a militant organisation in Sri Lanka. He also alleged that the LTTE cadres were given military training in Tamil Nadu, and that Ramachandran had gifted ₹40 million (US$470,000) rupees to the group without the knowledge of the Indian government.[76]

Ramachandran's government often used state machinery against political criticism and opposition.[68] In April 1987, the editor of Ananda Vikatan S. Balasubramanian was sentenced to 3 months in jail by the Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly for publishing a cartoon, depicting government ministers as bandits and lawmakers as pickpockets, though specific legislature was not specified. He was later released due to media outcry and Balasubramanian won a case against his arrest. Vaniga Otrumai editor A.M. Paulraj was also sentenced to two weeks imprisonment by the assembly for his writing.[77][78]

Elections results

[edit]- Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly

| Elections | Assembly | Constituency | Political party | Result | Vote percentage | Opposition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Political party | Vote percentage | |||||||||

| 1967 | 4th | St. Thomas Mount | DMK | Won | 66.67% | T. L. Raghupathy | INC | 32.57% | |||

| 1971 | 5th | 61.11% | INC(O) | 38.10% | |||||||

| 1977 | 6th | Aruppukottai | AIADMK | 56.23% | M. Muthuvel Servai | JP | 17.87% | ||||

| 1980 | 7th | Madurai West | 59.61% | Pon. Muthuramalingam | DMK | 37.59% | |||||

| 1984 | 8th | Andipatti | 67.40% | Thangaraj | 31.22% | ||||||

Positions held

[edit]| Elections | Position | Constituency | Term in office | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assumed office | Left office | Time in office | |||

| 1962 | Member of the Legislative Council | — | 30 March 1962 | 7 July 1964 | 2 years, 99 days |

| 1967 | Member of the Legislative Assembly | St. Thomas Mount | 15 March 1967 | 5 January 1971 | 3 years, 296 days |

| 1971 | 22 March 1971 | 31 January 1976 | 4 years, 315 days | ||

| 1977 | Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu | Aruppukottai | 30 June 1977 | 17 February 1980 | 2 years, 232 days |

| 1980 | Madurai West | 9 June 1980 | 9 February 1985 | 4 years, 245 days | |

| 1984 | Andipatti | 10 February 1985 | 24 December 1987 | 2 years, 317 days | |

Illness and death

[edit]

In October 1984, Ramachandran was diagnosed with kidney failure as a result of uncontrolled diabetes, which was soon followed by a heart attack and stroke.[79][80] He underwent a kidney transplant at the Downstate Medical Center in New York City, United States. He returned to Madras on 4 February 1985 following his recovery.[81]

Over the next three years, Ramachandran had frequent trips to the United States for treatment. He never fully recovered from his health issues and died on 24 December 1987 at 3:30 am in his Ramavaram Garden residence in Manapakkam at the age of 70.[82] His body was kept in state at Rajaji Hall for two days for public viewing. On 25 December 1987, his remains were buried at the northern end of the Marina beach, now called MGR Memorial, adjacent to the Anna Memorial.[83] Around one million people were estimated to have attended his funeral.[84]

Ramachandran's death sparked a frenzy of public rioting over the state, and various shops, cinemas, buses and other public and private property became the target of the violence. The police were given shoot-at-sight orders to bring the situation under control. Schools, colleges and various establishments announced holidays due to the situation. The state of affairs continued for almost a month across Tamil Nadu. Some women allegedly shaved their heads bald, and dressed like widows. A few whipped or self immolated themselves. Violence during the funeral alone left 129 people dead and 47 police personnel wounded.[85][86][87]

Personal life

[edit]

In 1939, Ramachandran married Chitarikulam Bhargavi, who later died in 1942 due to an illness. In late 1942, he married Sadanandavati, who died later due to tuberculosis in 1962.[88][89] In 1963, he married actress V. N. Janaki, who later became the chief minister of Tamil Nadu after his death.[89][90] He had no biological children from any of his marriages.[91]

In his early days, Ramachandran was a devout Hindu and a devotee of Murugan and his mother's favourite god, Guruvayurappan.[92] After joining the DMK, he identified himself as a rationalist.[93] He gifted a golden sword weighing half a Kilogram to Mookambika temple in Kollur, Udupi district.[94]

Ramachandran was the founder and editor of Thai weekly magazine and Anna daily newspaper in Tamil.[citation needed] He established Sathya Studios and Emgeeyar Pictures.[95] He offered personal financial donations during disasters and calamities, and donated Rs. 75,000 to the war fund during the Sino-Indian War.[96]

Legacy and honours

[edit]

Ramachandran was awarded honorary doctorates by The World University in 1974 for his contributions to Indian cinema,[97] and the University of Madras in 1987 for his contributions to public affairs.[98] On 19 March 1988, Ramachandran was posthumously honoured with Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian honour.[99] He became the third chief minister of the state to receive the award after C. Rajagopalachari and K. Kamaraj. The timing of the award was controversial, and his opponents criticised the central government led by Congress under Rajiv Gandhi to have influenced the decision to give the award to help win the upcoming 1989 Lok Sabha election.[100]

Ramachandran is widely known by the epithets "Makkal Thilagam" (Jewel of the People), "Puratchi Thalaivar" (Revolutionary Leader), and "Ponmana Chemmal" (Generous one) in Tamil Nadu.[101] In 1989, Dr. M. G. R. Home and Higher Secondary School for the Speech and Hearing Impaired was established at the his erstwhile residence in Ramapuram, in accordance with his last will and testament written in January 1987.[102] His official residence located at 27, Arcot Street, Thyagaraya Nagar was converted into a memorial house and opened for public viewing.[103] The Dr. MGR-Janaki College of Arts and Science for Women was established in a part of the land that housed Sathya Studios.[104]

A life-size statue of Ramachandran was unveiled on 7 December 2006 in the Parliament House by then Lok Sabha Speaker Somnath Chatterjee.[105] To commemorate Ramachandran's birth centenary in 2017, the Reserve Bank of India issued Rs. 100 and Rs.5 coins that bore his image as a portrait along with an inscription mentioning the event.[106]

Several localities, roads, places, and establishments have been named in his honour. MGR Nagar, a residential neighbourhood in Chennai was named after him.[107] Chennai Mofussil Bus Terminus,[108] Salem Central Bus Stand,[109] Tirunelveli New Bus Stand,[110] and M.G.R. Bus Stand at Madurai are named after him.[111] On 5 April 2019, Government of India renamed the Chennai Central railway station as Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. M.G. Ramachandran Central Railway Station to honour him.[112] On 31 July 2020, Central Metro station of the Chennai Metro was renamed after Ramachandran.[113] On 17 October 2021, the AIADMK headquarters in Royapettah was renamed as Puratchi Thalaivar M.G.R. Maaligai by party leaders in memory of the party's founder.[114]

Film awards

[edit]| Year | Event | Category | Film | Conferred by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 19th National Film Awards | Best Actor in a Leading Role | Rickshawkaran | Government of India |

| 1968 | 2nd Tamil Nadu State Film Award | Best Actor | Kudiyirundha Koyil | Government of Tamil Nadu |

| 1969 | 3rd Tamil Nadu State Film Award | Best Film | Adimai Penn | |

| 1978 | 12th Tamil Nadu State Film Award | Special Award | Madhuraiyai Meetta Sundharapandiyan | |

| 1965 | 13th Filmfare Awards South | Special Award – South | Enga Veettu Pillai | Filmfare |

| 1969 | 17th Filmfare Awards South | Best Film – Tamil | Adimai Penn | |

| 1973 | 21st Filmfare Awards South | Special Award – South | Ulagam Sutrum Valiban |

In popular culture

[edit]Ramachandran's autobiography, "Naan Yaen Piranthen? (Why Was I Born?)", was published in 2003.[115]

The 1997 Tamil film Iruvar, by Mani Ratnam, is based on the rivalry between Ramachandran and Karunanidhi. Mohanlal played Anandan, the character based on Ramachandran.[116] In the 2019 web series Queen, Indrajith Sukumaran portrayed G. M. Ravichandran, the fictional adaptation of Ramachandran.[117] In the Tamil film Thalaivii (2021), Ramachandran was portrayed by Arvind Swamy.[118][119]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ V. R. Nedunchezhiyan served as acting chief minister in the interim for 14 days.

References

[edit]- ^ "Madras Legislative Assembly 1962–67 : A Review" (PDF). Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ a b "MGR remembered". The Times of India. 24 December 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ Sri Kantha, Sachi (8 April 2015). "M.G.R. Remembered – Part 26". Sangam.org. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ "Modi to Mamata, M.G.R. to NTR: Vir Sanghvi lists 70 politicians who changed India". The Hindustan Times. 15 August 2017. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ a b "MGR filmography". Golden Tamil Cinema. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Events – MGR-Sivaji-Gemini: Trinity Album Launched". Indiaglitz. 9 July 2012. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ Kumaresan, S (27 April 2021). "From the archives: Why is 1980 Tamil Nadu Assembly election worthy of note?". The New Indian Expressaccess-date=27 April 2021. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022.

- ^ Kumaresan, S (28 April 2021). "From the archives: When MGR sailed on sympathy in 1984 polls". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Aiyar, Mani Shankar (1 January 2009). A Time of Transition: Rajiv Gandhi to the 21 Century. Penguin Books India. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-670-08275-9.

- ^ Gough, Kathleen (1989). Rural Change in Southeast India 1950s to 1980s. Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-195-62276-8.

- ^ "108th birth anniversary of M.G. Ramachandran celebrated in Jaffna". Tamil Guardian. 21 January 2025. Archived from the original on 10 February 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ Kannan, R. (28 June 2017). M.G.R.: A Life. Penguin Random House. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-14-342934-0.

MGR has said that his ancestors were originally from Pollachi, and were Mandradiyars of the Kongu Vellalars...MGR greatly resented being considered a Malayali

- ^ Krishnamachari, Suganthi (30 April 2020). "Inscriptions talk of fascinating Kongu connection". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

Krishna Menon of the Valluva Nadu royal family had five sons, of whom the fourth was Sankunni Valiya Mannadiyar, born in 1832. Sankunni Mannadiyar held a judicial post in Cochin. His son was Gopala Menon, born in 1884. Gopala Menon's wife, Satyabhama, belonged to a family in Mathur, which was referred to as Vadavanur Vellalar in copper plates. To Gopala Menon and Satyabhama, a son was born in 1917, who was to become famous not only in Tamil films, but in the political scene in Tamil Nadu. That son was M.G. Ramachandran! So M.G.R. had Kongu Vellala ancestors, both on his father's side and mother's side!

- ^ Kumar, N. Vinoth (8 April 2023). "A book sought to prove MGR was a Gounder from Kongu land; what was the aim?". The Federal. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "MGR's childhood home in Kerala to become a cultural hub". The Times of India. 14 February 2018. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Veeravalli, Shrikanth. "MG Ramachandran's early years: a poor childhood, drama school, and the first big break". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "M. G. Ramachandran Summary and Analysis Summary". Bookrags. 3 March 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Americans in Tamil cinema". The Hindu. 6 September 2004. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ^ Guy, Randor (28 March 2008). "Meera 1945". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Guy, Randor (5 September 2008). "Rajakumari 1947". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Actor‑turned‑politician MGR's 108th birth anniversary today: 'His work inspires us,' PM Modi pays homage to superstar of Tamil cinema". Bhaskar English. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ a b "MGR Remembered – Part 6". Ilankai Tamil Sangam. 2 February 2013. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ Guy, Randor (14 March 2008). "Marmayogi 1951". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Phadnis, Aditi (6 December 2016). "Jayalalithaa: Tamil Nadu's mercurial pharaoh". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 7 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Guy, Randor (28 November 2008). "En Thangai 1952". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves: The first colour Tamil film". DT Next. 3 July 2022. Archived from the original on 20 November 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ a b Mishra, Nivedita (17 January 2017). "MGR's centenary: The man who dominated Tamil films for 3 decades". The Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 7 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Guy, Randor (9 April 2011). "Chakravarthi Thirumagal 1957". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Guy, Randor (16 January 2016). "Mahadevi (1957)". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ "M.G Ramachandran Took Loan From This Producer to Buy Release Prints of Nadodi Mannan". News18. 24 August 2022. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Two kings: MGR's Nadodi Mannan took Madras by a storm". DT Next. 20 November 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2025.

- ^ "A Tamil film that had aliens, spaceships, anti‑gravity boots half a century ago". The News Minute. 3 June 2016. Archived from the original on 28 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ Guy, Randor (30 January 2016). "Thozhilaali (1964)". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Guy, Randor (28 February 2016). "Padagotti (1964)". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ "The gunshot in MGR's ear that changed Tamil Nadu". Asianet News. 4 November 2016. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Those were the days: A bullet that changed the political career of MGR". DT Next. 28 October 2018. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "MG Ramachandran Awards: Achievements & Honors". The Indian Express. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Ulagam Sutrum Vaaliban (1973)". The Hindu. 30 April 2016. Archived from the original on 18 August 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "MGR-Sivaji-Gemini: Trinity Album Launched". IndiaGlitz. 22 January 2011. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ^ "MGR, man of the masses". The Hindu. 17 January 2018. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ "MGR Remembered – Part 2". Ilankai Tamil Sangam. 2 February 2013. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Saroja Devi: The Kannadathu Payinkili and Abinaya Saraswathi of Tamil cinema". The Hindu. 14 July 2025. Archived from the original on 15 July 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Pattikatu Ponnaiah: Jayalalitha And M G Ramachandran's Last Film Completes 50 Years". News18. 11 August 2023. Archived from the original on 15 August 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "The Genesis of AIADMK". The New Indian Express. 19 March 2021. Archived from the original on 20 February 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ A. Srivathsan (23 December 2012). "The day M.R. Radha shot MGR". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019.

- ^ "When the hero M.G. Ramachandran was shot at by villain M.R. Radha". The Hindu. 26 November 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Dravidian Chronicles: MGR's first electoral victory was from a hospital bed". The News Minute. 20 April 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ Selvaraj Velayutham (2008). Tamil cinema: the cultural politics of India's other film industry. New York city: Routledge. p. 1967. ISBN 978-0-415-39680-6.

- ^ "Best of friends, worthy rivals". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 18 April 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ a b c "எம்.ஜி.ஆரை நீக்கியதன் விளைவை தி.மு.க சந்திக்கும்!" அப்போதே எச்சரித்த ராஜாஜி" ["DMK will the face the consequences of removing MGR", warned Rajaji]. Vikatan (in Tamil). 20 October 2019.

- ^ "The MGR magic: Looking back at how cinema propelled the leader of the AIADMK". The News Minute. 17 January 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Elections that shaped India: Janata Party wave takes over in 1977". The Hindu. 4 April 2024. Archived from the original on 23 February 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "When a historic election in 1977 turned Tamil Nadu political landscape bipolar". The Hindu. 3 September 2025. Archived from the original on 3 September 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "How the 1977 Assembly election defined the political landscape of Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. 2 July 2024. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ a b c "Tamil Nadu polls 2016: A look at past results (1952‑2011)". OneIndia. 10 May 2016. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ a b c "List of Chief Ministers of Tamil Nadu". OneIndia. Archived from the original on 3 December 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "MGR got equation right with Centre to get State fair share of benefit, influence decisions". The New Indian Express. 24 December 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Never fight with Delhi". The Hindu. 23 March 2016. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ a b "Indira Gandhi never forgave MGR for 1977". The News Minute. 1 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2 April 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu News : AIADMK came close to merging with DMK: Karunanidhi". The Hindu. 1 April 2009. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "Karuna recalls Biju's bid for DMK-AIADMK merger". Zee News. 13 May 2012. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "How Biju Patnaik nearly pulled off a DMK and AIADMK merger". News Minute. 20 April 2016.

- ^ "1984: Assassination and revenge". BBC News. 31 October 1984. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ Mollan, Cherylann (28 June 2025). "A pioneering doctor remembers India leader Indira Gandhi's final moments". BBC News. Archived from the original on 29 June 2025. Retrieved 29 June 2025.

- ^ "When MGR fell ill". Frontline. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Where's The Personal Doc?". Outlook. 5 December 2019. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "AIADMK‑Congress combine ride on sympathy wave in '84". The New Indian Express. 4 March 2019. Archived from the original on 30 April 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ a b c M. S. S. Pandian (29 July 1989). "Culture and Subaltern Consciousness: An Aspect of MGR Phenomenon". Economic and Political Weekly. 24 (30): 62–68. JSTOR 4395134. Archived from the original on 6 April 2024. Retrieved 5 October 2025.

- ^ "Polls show MGR as the best CM of Tamil Nadu". OneIndia. 20 December 2006. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "The prince of populism". The Hindu. 17 January 2017. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Book Excerpt: MGR, the Man Who Fed 66 Lakh Children With His Nutritious Mid‑Day Meal Scheme". The Better India. 1 July 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ Ramakrishnan, T. (29 August 2023). "How Tamil Nadu created history through mid‑day meal scheme". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 February 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu's Unsustainable Energy Policy". Spontaneous Order. 14 August 2021. Archived from the original on 18 April 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ Ingrid Widlund (1993). "A Vote for MGR Transaction and Devotion in South Indian Politics". Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrifts. 96 (3): 225–257. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ "First state to have prohibition, now govt‑run liquor shops pervade TN". The New Indian Express. 30 July 2022. Archived from the original on 21 November 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Natwar exposes Rajiv's dealings with LTTE". The Sunday Times. 3 August 2014. Archived from the original on 17 February 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Arresting affair Arrest of Ananda Vikattin editor another press vs Ramachandran Government battle". S.H. Venkatramani. 30 April 1987. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Ramachandran, K. (16 November 2003). "A trophy to remember". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Venkatramani, S. H. (15 November 1984). "M.G. Ramachandran's kidney ailment remained a well-kept secret". India Today. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "MGR dies of heart attack". The Indian Express. 25 December 1987. p. 1. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ Sethi, Sunil (28 February 1985). "Tamil Nadu CM M.G. Ramachandran returns home, health speculations laid to rest". India Today. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "M.G. Ramachandrans death marks the passing of an era of stability in Tamil Nadu". India Today. 15 January 1988. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Tripathi, Ashutosh (6 December 2016). "Rajaji Hall: A Witness to History and Events in Tamil Nadu". News18. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "One Million Indians Mourn Tamil Leader". Charlotte Observer. 26 December 1987. Archived from the original on 24 March 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- ^ "Politics and suicides". The Hindu. 2 June 2002. Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ "Popular Tamil Leader Dies in India;Rioting, Suicides Follow Death of Tamil Nadu's Chief Minister". PQASB. 25 December 1987. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "Tamil leader's death stirs India riots". Chicago Sun-Times. 26 December 1987. Archived from the original on 23 March 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- ^ "திருமணமும் தகுதி உயர்வும்" [Marriage and promotion]. Maalaimalar (in Tamil). 19 February 2014. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Actor-Politician MGR's Marital Life - A Tragic Tale". News18. Archived from the original on 17 January 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "பொன்மனச் செம்மலின் வெற்றி வரலாறு (பகுதி 5): வி.என். ஜானகியை வாழ்க்கைத் துணைவியாக ஏற்றார்!" [Life history of MGR Part 5: Marriage with V.N.Janaki]. Maalaimalar (in Tamil). 19 February 2014. Archived from the original on 24 January 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ Thomas, K.M. (27 April 1998). "Family feud over MGR's property turns into public campaign against controlling authority". India Today. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Linda Woodhead. Religions in Modern World. Fletcher, Kawanam. p. 39.

- ^ M.S.S. Pandian (1992). The image trap: M G Ramachandran in Film and Politics. SAGE Publications. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-803-99403-4.

- ^ "Jayalalithaa offers prayers at Kollur temple". The Hindu. 31 July 2004. Archived from the original on 22 August 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "AIADMK founder MG Ramachandran's will may hold key to ongoing leadership tussle". The New Indian Express. 4 July 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "1962 India‑China war: Why India needed that jolt". The Economic Times. 7 October 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "TN CM to receive honorary doctorate from Dr MGR Educational and Research Institute". News Minute. 16 October 2019. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "M.G.R. biography". MGR home. Archived from the original on 21 January 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "List of Bharat Ratna award winners from 1954 to 2024". The Times of India. 12 August 2024. Archived from the original on 17 February 2025. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

- ^ "Bharat Ratna- Isn't the arbitrary selection & politics making this highest civilian award controversy prone?". Merinews. 20 November 2013. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ "Ponmana Chemmal M G Ramachandran". Kalki (in Tamil). 3 January 1988. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "M. G. R. Home and Higher Secondary School for the Speech and Hearing Impaired". Enabled. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "MGR Illam gives a glimpse into a charismatic actor‑politician's life". The Hindu. 7 January 2024. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "K Subrahmanyam Hall to be opened tomorrow". Deccan Chronicle. 29 August 2018. Archived from the original on 20 April 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Statues of MGR, Bhupesh Gupta unveiled in Parliament". OneIndia. 7 December 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Centre to mint ₹5, ₹100 coins to commemorate MGR's birth centenary". The Hindu. 12 September 2017. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Residents want new street-name boards to be installed at MGR Nagar in Chennai". The Hindu. 10 June 2025. Archived from the original on 10 June 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "CMBT renamed as 'Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. MGR Bus Terminus'". The New Indian Express. 10 October 2018. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ "Salem news bus stand renovated at a cost of 24.8 lakhs". The Hindu. 5 October 2024. Archived from the original on 6 October 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ Government of Tamil Nadu, Tirunelveli District Administration (8 December 2021). "The Hon'ble Chief Minister inaugurated the renewed Bharat Ratna Dr. MGR Bus Stand and Palayamkottai Bus Stand under the Smart City Projects through video conferencing" (PDF). Tirunelveli district. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "It is now MGR bus stand at Mattuthavani". The Hindu. 31 October 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ M, Manikandan (5 April 2019). "Chennai Central railway station renamed after AIADMK founder MGR". The Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu government to rename three metro rail stations in Chennai after late Chief Ministers". The New Indian Express. 31 July 2020. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ "எம்ஜிஆர் மாளிகை' ஆனது அதிமுக அலுவலகம்: பொன் விழாவை சிறப்பாக கொண்டாட ஏற்பாடு" [ADMK office becomes MGR maaligai]. Dinamalar (in Tamil). 15 October 2021. Archived from the original on 15 December 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "Janaki's son alone has copyright to M.G.R.'s autobiography: court". The Hindu. 4 July 2012. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ "When Mohanlal humanised MGR in Mani Ratnam's Iruvar". The New Indian Express. 20 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ "Indrajith Sukumaran to play MGR in Gautham Menon's Jayalalithaa web series". Cinema Express. 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Team 'Thalaivi' shares new look of Arvind Swami as MGR on his death anniversary". The New Indian Express. 24 December 2020. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Ramanujam, Srinivasa (8 September 2021). "Becoming MGR: How Arvind Swami got into shape for 'Thalaivii'". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

External links

[edit]- M. G. Ramachandran

- 1917 births

- 1987 deaths

- 20th-century Indian male actors

- Actors from Kandy

- Actors in Hindi cinema

- Actors in Tamil cinema

- Best Actor National Film Award winners

- Chief ministers from All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam

- Chief ministers of Tamil Nadu

- Film directors from Chennai

- Film producers from Chennai

- Filmfare Awards South winners

- Indian actor-politicians

- Indian Hindus

- Indian male film actors

- Indian political party founders

- Indian Tamil politicians

- Kidney transplant recipients

- Malayali people

- Male actors from Chennai

- Male actors in Malayalam cinema

- Actors from Thanjavur district

- Politicians from Thanjavur district

- Politicians from Chennai

- Recipients of the Bharat Ratna

- Recipients of the Padma Shri in arts

- Sri Lankan emigrants to India

- Tamil film producers

- Tamil Nadu MLAs 1967–1971

- Tamil Nadu MLAs 1971–1976

- Tamil Nadu MLAs 1977–1980

- Tamil Nadu MLAs 1980–1984

- Tamil Nadu MLAs 1985–1989

- Tamil Nadu State Film Awards winners

- Tamil-language film directors