Jōdo Shinshū

Jōdo Shinshū (浄土真宗, "The True Essence of the Pure Land Teaching"), also known as Shin Buddhism or True Pure Land Buddhism, is a Japanese tradition of Pure Land Buddhism founded by Shinran (1173–1263).[1] Shin Buddhism is the most widely practiced branch of Buddhism in Japan, and its membership is claimed to include 10 percent of all Japanese citizens.[2][3] The school is based on the Pure Land teachings of Shinran, which are based on those of earlier Pure Land masters Hōnen, Shandao and Tanluan, all of whom emphasized the practice of nembutsu (the recitation of Amida Buddha's name) as the primary means to obtain post-mortem birth in the Pure Land of Sukhavati (and thus, Buddhahood).

Shinran taught that enlightenment cannot be realized through one’s own self-power (jiriki), whether by moral cultivation, meditation, or ritual practice, but only through the other-power (tariki) of Amida Buddha’s compassionate Vow. Therefore, in Shin Buddhism, the nembutsu is not a meritorious deed or practice that produces merit and liberation, but an expression of joyful gratitude for the assurance of rebirth in the Pure Land, which has already been granted by Amida’s inconceivable wisdom and compassion. Doctrinally, Jōdo Shinshū is grounded in Shinran’s magnum opus, the Kyōgyōshinshō (Teaching, Practice, Faith, and Realization), which presents a comprehensive exegesis of Pure Land thought based on Indian and Chinese Mahāyāna sources. Shinran’s synthesis reframes the Pure Land path as the culmination of Mahāyāna Buddhism, emphasizing ideas like true faith (shinjin), other-power, the abandonment of self-power, the nembutsu of gratitude, and the all-embracing compassion of Amida Buddha's Original Vow.

After Shinran's death, his followers organized his teachings into traditions that eventually took institutional form through various temple lineages like the Honganji, which became major religious and social forces in medieval and early modern Japan. Figures like Kakunyo, Zonkaku and Rennyo further developed Shin Buddhist doctrine and practice through their teaching and scholarship, expanding on the foundations laid by Shinran. According to James Dobbins, "historically, the Shinshū derives its strength from the great number of ordinary people drawn to its simple doctrine of salvation through faith".[4] Its simple and popular message, along with the tireless work of leaders like Shinran and Rennyo led Shin to become the largest Buddhist school in Japan by the sixteenth century.[4]

In the modern era, the tradition also expanded to the West, with Japanese diaspora organizations like Buddhist Churches of America developing unique expressions of Shin Buddhism. Jōdo Shinshū continues today as a central expression of lay-oriented Japanese Buddhism, emphasizing humility, gratitude, and faith in Amida’s boundless vow that carries all devotees to the Pure Land after death.

History

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Pure Land Buddhism |

|---|

|

Shinran

[edit]Shinran (1173–1263) lived during the late Heian to early Kamakura period (1185–1333), a time of turmoil for Japan when the Emperor was stripped of political power by the shōguns. Shinran's Hino family was a cadet branch of the Fujiwara that had lost its former status but remained known for scholarly service. Early bereavements, including the probable deaths of both parents, placed Shinran's upbringing in the care of his uncles. In 1181, amid the instability of the late Heian period, he entered monastic life at age nine under the Tendai prelate Jien and received the name Han’en. For the next two decades he lived as a modest hall-monk on Mount Hiei, engaged primarily in liturgy, chanting, and Pure Land–oriented practices associated with Genshin’s lineage, though little else from this period can be historically verified.[5]

Around 1201 Shinran, troubled by his inability to attain spiritual progress, undertook a retreat at the Rokkaku-dō. There, he reportedly experienced a revelatory vision of Prince Shōtoku directing him to the Pure Land master Hōnen (1133–1212). On meeting Hōnen that same year, Shinran adopted exclusive nembutsu practice and joined the growing community of Hōnen’s followers, abandoning other Tendai disciplines. Shinran played an important role in copying and transmitting Pure Land texts, and Hōnen’s entrusting of Shinran with a copy of the Senchakushū signified recognition of him as a disciple.[6] At some point Shinran also married (at a date still debated by scholars) entering a new status as a cleric who neither fully retained nor fully relinquished monastic identity.

During this period, Hōnen taught exclusive nembutsu practice to many people in Kyoto and amassed a substantial following but also came under increasing criticism by the Buddhist establishment, who continued to criticize Hōnen even after they signed a formal pledge to behave with good conduct and to not slander other Buddhists.[7] In 1207 a political scandal led to the suppression of Hōnen’s movement. Two disciples were executed, while Hōnen and others, including Shinran, were defrocked and exiled.[8] Shinran was sent to Echigo, where he and his wife Eshinni lived under difficult but mitigated conditions due to local family connections. Shinran and Eshinni had several children.

After their amnesty in 1211, Shinran remained in Echigo for two more years before moving to the Kantō region. During this transition he definitively abandoned complex practices after reflecting on their insufficiency compared to entrusting faith in Amida’s vow. He adopted the names Shinran and Gutoku (Bald Fool), identifying himself as “neither monk nor layman.” Over the following two decades he taught throughout Kantō, forming networks of lay communities (monto) that met in small dojos to recite the nembutsu and study his guidance. Through active correspondence and sustained teaching, he gathered numerous disciples across varied social strata.[9]

In the 1230s Shinran returned to Kyōto, where he spent his later years writing, compiling, and transmitting Pure Land doctrine. His major work, the Kyōgyōshinshō (The True Teaching, Practice, Faith and Attainment), presented an extensive scriptural anthology with doctrinal commentary defending Hōnen’s teaching and articulating Shinran’s own understanding of faith [8] He also produced Japanese didactic hymns, commentaries, compilations of Hōnen’s writings, and many letters addressing disciples’ concerns. Though living simply and relying on support from Kantō followers, he remained intellectually active well into old age. His final years were marked by both literary productivity and personal turbulence, including the need to disown his son Zenran for disruptive conduct and false doctrinal claims. Through his teaching, writing, and community networks, Shinran laid the foundations for what later became Jōdo Shinshū.[10]

Shinran's daughter, Kakushinni, came to Kyoto with Shinran, and cared for him in his final years. Shinran's wife Eshinni also wrote many letters which provide critical biographical information on Shinran's life. These letters are currently preserved in the Nishi Hongan temple in Kyoto. Shinran died at the age of 90 in 1263 (technically age 89 by Western reckoning).[8]

After Shinran

[edit]

From the thirteenth century to the fifteenth century, Shin Buddhism grew from a small movement into one of the largest and most influential schools in Japan. Its popularity among the lower classes in the countryside was a major reason for this rapid growth. In many rural villages, especially in semi-autonomous villages that were not tied to rural estates, Shin Buddhist congregations became a central part of village life. Pure Land missionaries traveled widely during this time spreading the Pure Land teaching, and Shin Buddhist temples were in a good position to absorb many of the new converts and to minister to the lower classes.[11] During this period of sect formation, Shin Buddhists developed their school's doctrine, forms of worship, and systems of religious authority based around temples.[12]

Shinran did not concern himself with establishing a temple or any organization in his lifetime, instead, his followers returned to their communities after learning from him, and created informal groups of lay Pure Land followers. These groups met in dōjōs, which were usually small private residences turned into meeting spaces. They met on the 25th of each month, recited the nembutsu and listened to sermons or sutras. They used vertical scrolls with the nembutsu as their main object of worship. Often the calligraphy on these scrolls would be from Shinran himself.[13] Unlike temples, dōjōs were usually run collectively by all members rather than hierarchically by a single priest. Members would usually agree to follow certain rules of conduct which were posted for all to see. Dōjōs were supported by the private donations of all members, unlike established temples which relied on their estates and on elite support.[14] Because much of Shin Buddhism was based on networks of private dōjōs, it did not suffer like other schools from the collapse of the provincial estate system during the 15th and 16th centuries.[15]

Shinran kept in touch with the network of his followers through letters, many of which survive.[13] After his death, his family members and key disciples continued to support and lead local communities through a loose network of groups and temples. Around eighty major disciples of Shinran are known from the sources. Some of the most important communities include those of Shimbutsu (1209-1258), of his son-in-law Kenchi (1226-1310) in Takada, the congregation founded by Shōshin (1187- 1275) in Yokosone, and Shinkai's in Kashima.[16]

Shinran's teachings spread in the context of Kamakura period Pure Land Buddhism, a movement that was seen as heretical by most of the orthodox schools of Japanese Buddhism at the time. The Pure Land movement was very internally diverse, and different groups within engaged in intense debates about key issues. These included the debate between reciting the nembutsu many times or just once, and the debate on whether wrong deeds and violation of precepts were made acceptable by one's recitation of the nembutsu (also known as licensed evil), a view which was deemed heretical by most of the major Pure Land institutions and temples at the time.[17]

Shinran's teaching focused on faith (shinjin) and de-emphasized the keeping of clerical precepts or extensive recitation of the nembutsu. As such, Shin followers were often criticized as heretical, even by other Pure Land Buddhists. The Chinzei branch of Jōdo-shū for example, attacked Shin Buddhism as just another form of the single recitation (ichinengi) doctrine of Kōsai, which it associated with the licensed evil heresy. This was not an accurate critique since Shinran had explicitly rejected both views, but it was a damaging charge nevertheless.[18] In response, Shin Buddhist leaders like Kakunyo and Zonkaku worked to defend and establish Jōdo Shinshū as a viable and orthodox tradition, critiquing the "licensed evil" view along with other heresies and developing a scholastically robust tradition.

The rise of the temple sects

[edit]

Following Shinran's death, lay Shin monto or congregations spread through the Kantō plain and along the northeastern seaboard of Honshu. Kakushinni officially placed the lands of Shinran's mausoleum under a community of local Shin followers on the agreement that her descendants would become its hereditary caretakers. Kakushinni and her heirs were also instrumental in preserving and promoting Shinran's teachings. A chapel with a statue of Shinran was constructed on the site of the mausoleum, and Shinran's followers gathered at the site every year to commemorate his death, a week long ritual that became known as Hōonkō. Thus, Shinran's direct descendants maintained themselves as caretakers of Shinran's gravesite and as Shin teachers.[19]

During the 14th century, the mausoleum grew to become a major temple and sub-sect of Jōdo Shinshū through the efforts of Kakunyo, Kakushinni's grandson. As the third monshu (caretaker) of Shinran's mausoleum, Kakunyo transformed the site into the influential Honganji ("Temple of the Original Vow"). He also compiled the first biography of Shinran, the Godenshō.[19]

Kakunyo’s career was marked by sustained efforts to consolidate the Honganji institution and to assert a unified lineage for Shin Buddhism centered on the Honganji. Kakunyo turned to textual and genealogical strategies to legitimate Honganji authority, placing himself as the direct successor of Shinran in both teaching and blood lineage. His writings sought to anchor the center of the Pure Land community firmly at Honganji by presenting Kakunyo as Shinran’s rightful doctrinal and institutional heir.[20] Doctrinally, Kakunyo was a rigorous defender of Shinran’s teaching that shinjin alone is the decisive cause of birth in the Pure Land, with the nembutsu functioning as its spontaneous expression. His position diverged sharply from the dominant Jōdo-shū view that emphasized the efficacy of nembutsu recitation itself. At the institutional level he established memorial rites, produced hagiographies, and created ritual structures designed to cultivate devotion to Shinran as a manifestation of Amida Buddha. Through works like the Hōon kōshiki, he reframed nembutsu practice in terms of responding to the Buddha's benevolence, making hōon (gratitude) the central mode of Shin Buddhist piety and a key means of establishing a karmic connection with Amida embodied in the figure of Shinran.[21] Kakunyo's son, Zonkaku, was another influential scholar of the Honganji tradition. Zonkaku devoted himself to the expansion of Jōdo Shinshū’s religious community and produced numerous scholarly works defending Shin teachings.

As the Honganji became an influential Shin institution, other major Shinshū temples also developed, like Bukkō-ji, Senju-ji, Kinshoku-ji, and Zenpuku-ji. Most of these grew organically out of existing dojos who often consolidated their networks around the most influential temples.[22] Bukkō-ji was particularly influential and rivaled Honganji for some time, having been founded as a temple and expanded by the efforts of Ryōgen (1295–1336) and Zonkaku. Tensions and disagreements between Kakunyo and Zonkaku led to a break between Honganji and Bukkō-ji which would not be healed until the time of Rennyo.

During this period of sect formation, Shin clergy continued to be ordained and educated in traditional Japanese institutions, like those of Tendai and the old Nara schools, though they also received instructions from their Shin elders. For example, both Kakunyo and Zonkaku studied on Mount Hiei and Kōfuku-ji before becoming major Shin leaders.[23] This continued until Shin temples began to establish their own official education structure and ordination system. Though Shin priests eventually came to be ordained through official Shin temple systems, they did not take traditional Vinaya precepts, nor the bodhisattva precepts required in Tendai and other Japanese traditions. Nevertheless, they still underwent tonsure (tokudo), wore monastic robes and were expected to follow certain codes of conduct agreed upon by their communities.

Rennyo's revival

[edit]

Shin Buddhism is considered to have undergone a revival and consolidation period under Rennyo (1415–1499), who was 8th in descent from Shinran. Through his charisma and proselytizing, Shin Buddhism was able to amass a greater following and grow in strength.

Despite living in the war torn Sengoku era, Rennyo was able to unite most of the disparate factions of Shinshu under the influence of the Hongan-ji. He also reformed existing liturgy and Shin practices, and broaden support among different classes of society. Through Rennyo's efforts, Jodo Shinshu grew to become the largest, most influential Buddhist sect in Japan. For this he is often called "The Restorer" (Chūkō no sō).

During the time of Shinran, followers would gather in informal meeting houses called dojo, and had an informal liturgical structure. However, as time went on, this lack of cohesion and structure caused Jōdo Shinshū to gradually lose its identity as a distinct sect, as people began mixing other Buddhist practices with Shin ritual. One common example was the Mantra of Light popularized by Myōe and Shingon Buddhism. Other Pure Land Buddhist practices, such as the nembutsu odori[24] or "dancing nembutsu" as practiced by the followers of Ippen and the Ji-shū, may have also been adopted by early Shin Buddhists. Rennyo ended these practices by formalizing much of the Jōdo Shinshū ritual and liturgy, and revived the thinning community at the Hongan-ji temple while asserting newfound political power. Rennyo also proselytized widely among other Pure Land sects and consolidated most of the smaller Shin sects. Today, there are still ten distinct sects of Jōdo Shinshū with Nishi Hongan-ji and Higashi Hongan-ji being the two largest.

Rennyo is generally credited by Shin Buddhists for reviving the Jōdo Shinshū community, and is considered the "Second Founder" of Jōdo Shinshū by the Honganji tradition. His portrait picture, along with Shinran's, are present on the onaijin (altar area) in Honganji school Jōdo Shinshū temples. However, Rennyo has also been criticized by some Shin scholars for his engagement in medieval politics and his alleged divergences from Shinran's original thought. Furthermore, Jōdo Shinshū sects that remained independent of the Honganji school, such as the Senju-ji sect, do not recognize Rennyo's reforms and innovations.

Later developments

[edit]

During the Sengoku period (mid 15th century to late 16th c.), there were also other popular Shin Buddhist organizations, including the radical Ikkō-shū and the martial Ikkō-ikki ("single-minded leagues"). The Ikkō-ikki were armed bands of Shin followers that formed throughout the Sengoku period, often for self-defense purposes or in opposition to local governors or daimyō. In some cases, these groups took over the local government. In the 15th‑century, Kaga region (Fukui Prefecture) Shin followers overthrew the local daimyō and governed the region for over a century. Rennyo tried to negotiate and work with these various factions, while also attempting to mollify the government who feared them. At different times in the history of the Honganji, such as during the time of Jitsunyo, and his grandson Shōnyo, the temple leaders worked with these various leagues and helped them organize.

Furthermore, the military power of the Ikkō-ikki also led to persecutions against Jōdo Shinshū Buddhists in several regions like Satsuma and Kagoshima, whose leaders came to see Shin followers as radicals or heretical (igi 異義, literally “different meaning”) and persecuted Shin followers throughout the 16th century. Other Buddhist sects often joined in these attacks, especially Tendai and Nichiren. In 1532, daimyō Hosokawa Harumoto, an aide to the shogun, allied with the Nichiren sect and burned down the Honganji. The Honganji headquarters then relocated to the Ishiyama Hongan-ji (modern day Osaka). These persecutions also led to the development of secret Shin groups such as the kakure nenbutsu, kakushi nenbutsu and kayakabe.[25] These communities would meet in secret places like mountain caves or private homes. Some of these groups also developed esoteric practices in which the true teacher (zenjishiki 善知識) was instrumental.[25] Some also became influenced by other teachings like local Shinto mountain religions.[25]

In the 16th century, the political power of Hongan-ji and the military activities of the Ikkō-ikki led to several conflicts between Shin Buddhists and the warlord Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582), culminating in a ten-year conflict over the location of the Ishiyama Hongan-ji complex, which Nobunaga coveted because of its strategic value. The temple complex of Ishiyama and the city that had grown around it (Osaka) had grown powerful enough to make Nobunaga feel threatened by its influence. The site was eventually destroyed during the Siege of Ishiyama Hongan-ji (1576-1580) and replaced with Osaka castle.

During the tumultuous transition from the Azuchi-Momoyama (1568-1600) to the Edo period, Junnyo (准如) emerged as the 12th head priest of the Honganji, though his path to leadership was fraught with contention. Born in 1577 as the fourth son of the previous leader, Kennyo, Junnyo was not the initial successor; that role fell to his elder brother, Kyōnyo. However, in a dramatic political intervention in 1593, the ruling hegemon Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598) forced Kyōnyo to abdicate. Hideyoshi based his decision on a disputed document, allegedly from their father, designating Junnyo as the true heir. This decision, likely influenced by Kyōnyo's more militant history and a desire by Hideyoshi to control the powerful Buddhist institution, installed the young Junnyo as the leader of what would later become known as the Nishi (West) Honganji. His tenure thus began under the shadow of his brother's illegitimate removal, a schism that would define his entire leadership.[26] Junnyo's early years as leader were dedicated to consolidating his fragile authority against his brother's lingering influence. Despite being forced into retirement, Kyōnyo did not fade into obscurity. He established a residence north of the main temple, the "Kita no Gosho," from which he continued to act as a rival religious leader. In response, Junnyo worked tirelessly to secure the loyalty of his retainers. This period was marked by intense internal division, with many families and followers torn between the two brothers.

The definitive split of the Honganji into two separate institutions was formalized in 1602 by the new shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu. In a strategic move often interpreted as an effort to weaken the Honganji's collective power, Ieyasu granted Kyōnyo a large plot of land in Kyoto, leading to the establishment of the Higashi (East) Honganji temple. This act officially divided the Jōdo Shinshū community into the (West) Nishi Hongan-ji, led by Junnyo, and the (East) Higashi Hongan-ji, led by Kyōnyo. They have remained separate institutions to this day.[27] While some historians view this as a deliberate "divide and rule" policy by Ieyasu, the Higashi Honganji's tradition maintains that Ieyasu was merely recognizing a pre-existing division, as the community had already functionally split into two opposing camps loyal to the respective brothers.[28]

Following the formal division, Junnyo faced ongoing challenges in stabilizing his sect. Defections to the Higashi Honganji continued, even among those who had previously sworn oaths to him. Junnyo responded by focusing on internal development and external diplomacy. He oversaw the reconstruction of the Nishi Honganji after a devastating fire and established several key branch temples (betsuin) across Japan to strengthen the sect's regional network. Recognizing the importance of political connections, he actively cultivated relationships with the Tokugawa shogunate and other powerful daimyō, making repeated visits to Edo to secure his sect's position in the new political order.[29]

Edo period

[edit]Following the unification of Japan during the Edo period (1600—1868), Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism adapted to the new danka system, which was made compulsory for all citizens by Tokugawa shogunate in order to prevent the spread of Christianity in Japan. According to the new laws, all Japanese were required to belong to a temple. Their funerals had to be held at their temple and their burials were held in the temple's cemetery. Temples kept records of all members, providing basic information about the residents. The danka system continues to exist today, although not as strictly as in the premodern period, causing much of Japanese Buddhism to also be labeled as "Funeral Buddhism", as funerary practices became a central function of Buddhist temples.

The Edo period also saw the development of a sophisticated academic tradition by the Hongan-ji schools, leading to the founding of major universities like Dōhō University in Nagoya, Ryukoku University and Ōtani University in Kyoto, and Musashino University in Tokyo. The establishment of Jōdo Shinshū universities in the Edo period emerged from several institutional pressures which required a more systematized clerical education. As major Shinshū branches expanded their bureaucratic structures, they developed increasingly sophisticated scholastic curricula in order to regulate doctrine, manage extensive temple networks, and cultivate a clerical elite capable of interacting with the state and their parishioners. This environment encouraged the formation of dedicated training academies or “gakuryō” (seminaries) within the Shinshū establishment, which laid the groundwork for later universities connected to the major Shinshū headquarters in Kyoto. These academies became centers not only for sectarian doctrine but also for broader learning, engaging with Buddhist studies, language studies, history and philosophy. Over time, these scholastic centers developed into formal Western-style universities, with departments studying secular fields alongside Buddhist studies.[30]

Modern era

[edit]

The modern history of Jōdo Shinshū is marked by the radical transformation of Japanese society from the Meiji era (1868–1912) onward. The Meiji Restoration (1868) led to significant changes in Japanese society and culture, which affected Buddhism deeply. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, new currents of Western philosophy, scientific rationalism, Japanese nationalism and State Shinto challenged inherited Buddhist worldviews, contributing to perceptions that traditional Pure Land doctrine was antiquated and not Japanese. Non-Buddhist voices such as Inoue Tetsujirō and Hirata Atsutane also directly attacked Buddhism as backwards, foreign and incompatible with modern Japan.[30]

Anti-Buddhist ideologies, along with the wish to appropriate economic power of Buddhist temples, led to the campaigns of anti-Buddhist persecution known as haibutsu kishaku ("drive out Buddhism, destroy Śākyamuni").[30] These were most serious between 1868 and 1872 and affected all Japanese Buddhist schools. In spite of this, a reconciliation period during the middle Meiji era led to efforts to enlist Buddhist institutions in support of government policy.[30] Also during this time, Japanese new religions began to develop and compete with established Buddhist schools. Christianity also became legal and Japanese Christians began to proselytize and criticize Buddhism.[30]

Shin Buddhists responded to the various pressures of this era with efforts to reform and modernize Shin education, expanding to include study of Christianity (to better refute it), Western Philosophy, ancient languages like Sanskrit, and Indology.[30] This period also saw the emergence of a reformist intellectual movement that articulated challenging interpretations of Shin teachings, often under the influence of Western thought and modern Buddhist studies.[30][27] Kiyozawa Manshi (1863–1903) is widely regarded as the first major "modern" Shinshū thinker who led a turn toward introspective, philosophical, and existentially framed interpretations of Shinran. His writings reinterpret Pure Land concepts in modern philosophical ways, emphasizing personal religious experience and interior realization. Kiyozawa also saw Amida Buddha as a symbol of “the infinite” rather than as a supernatural being, writing: "Amida Buddha is an expedient expression signifying the infinite, the universe as a whole, or the law that courses through and animates that universe."[27] Kiyozawa's way of thinking became extremely influential, leading to a new spiritual Shin orientation known as Seishinshugi (精神主義), which can be translated as “Cultivating Spirituality.” According to Mark Blum, Seishinshugi was "a set of principles that prioritized personal, subjective experience as the basis for religious understanding, as well as the praxis that ideally brought about realization."[30]

Kiyozawa gathered a group of followers called Kōkōdō, who published a journal named Seishinkai (Spiritual World). Kiyozawa and his followers argued for the transformation of Shin education away from the rigidity of traditional doctrinal study (shūgaku) that was based on acceptance of the sect's dogmas. He also argued that Shinran's teaching pointed to an experiential encounter with other power, something which he felt traditional Shin studies failed to communicate.[30] Although some of his contemporaries saw him as a marginal and ultimately unsuccessful reformer, his work became the foundation of later doctrinal and institutional transformation.[27] According to Blum, this movement was "the most important new conception of Shin thought since Rennyo reformed Honganji in the fifteenth century."[30]

Successive generations of Kiyozawa’s disciples, including Soga Ryōjin (1875–1971), Akegarasu Haya (1877–1954) and Kaneko Daiei (1881–1976), contributed to a broader modernist movement within Higashi Honganji that interpreted classic ideas from the perspective of inner religious experience. Kaneko also sought to integrate rationalism into Shin studies, asserting that even faith and nenbutsu must rest upon fundamental rational principles.[27] Kaneko also referred to the Pure Land as a kind of Platonic "idea" and a "transcendental ideal" that influences us here and now, rather than an actual location we reach after death.[27][30] Their attempts to articulate new doctrinal positions provoked major pushback from Ōtani sect traditionalists, leading to controversies that included accusations of heresy. Institutional conflicts at Ōtani University which included exlpulsions of Kiyozawa, Soga, and Kaneko, resignations, reinstatements, and mass student withdrawals reflected deep divisions between modernist reformers and defenders of traditional interpretations of Pure Land doctrine.[27][30]

While the conservative authors who rejected doctrinal modernist trends have often been depicted as mere reactionaries, they were just as sophisticated in their use of new philosophical concepts and modern media. The conservative critique of Seishinshugi modernism can be seen in the late writings of Murakami Senshō (1851–1929). Murakami had been part of the modernist movement himself, but he repudiated all of it in his late writings.[31] One of Murakami's main critiques focused on Kaneko's view of Amida and the Pure Land as a philosophical "idea", a view that rejected the existence of Amida as an actual being as "superstition". For Murakami, this view indicated that modernists like Kaneko failed to understand the real meaning of Pure Land Buddhism, and equated their rejection of the Pure Land with ancient "mind-only pure land" views influenced by Zen.[31] Also, from Murakami's point of view, it made no sense for someone who did not accept basic Pure Land principles to be a Shin cleric studying at Shin institutions. While the modernists wrote fine philosophy, it was not in line with the Shin faith, so they should do it outside of the Shin religion.[31]

Other important modern Shin authors of this period include Nanjō Bun'yū (1849–1927), Inoue Enryō (1858–1919), and Kenryō Kanamatsu (1915–1986). Takakusu Junjirō (1866–1945) was another key Shin figure of the era. He is known for his promotion of Buddhist education, founding of Musashino University (originally a women's school), and for leading the project to compile the Taisho Tripitaka, the most influential modern edition of the Chinese Buddhist Canon.[32] Some Shin scholars became known for their academic study of Buddhism, including Susumu Yamaguchi and Takamaro Shigaraki (1926–2014). Count Ōtani Kōzui, the 22nd monshu of Nishi Hongan-ji, was also known for his role in the exploration of Silk Road sites and the 1902 Ōtani expedition. Other figures wrote fiction based on Shinran, the most popular being Kurata Hyakuzō’s reading drama The Priest and His Disciples (1918).[33]

An influential Shin woman leader during the modern era was Takeko Kujō (1887–1928), one of the founders of the Buddhist Women's Association. Takeko led humanitarian efforts after the Great Kantō earthquake, including sponsoring the consturction of Asoka Hospital, one of Japan's first modern medical centers. She is also known for her Shin poetry and essays, some of which have been translated in Leaves of my Heart (2018).[34][35]

During Japan’s period of imperialistic wars, political pressure from the government added further complexity to internal debates within the Higashi sects. Both Higashi and Nishi Honganji had long maintained cooperative relationships with state authorities, a pattern intensified during the Pacific War (1931–1945). Under governmental demands to align Buddhist teaching with national ideology, Honganji leadership taught loyalty to the emperor and the state, censored scriptural passages critical of past emperors and supported state policies.[30][36] The 20th head of Nishi, Kōnyo, wrote an influential text that mapped obedience to the emperor and imperial law into the Buddhist concept of conventional truth, retaining the ultimate truth for religious matters.[37] Some modernist figures, including Soga and Kaneko, also advanced interpretations that could be assimilated to imperial nationalism, equating the Pure Land with the Japanese nation and Amida’s vows with imperial vows. After Japan’s defeat, Shin leaders acknowledged these wartime positions as mistaken and apologized for their acts.[38] The Allied occupation also purged several Buddhist leaders, and both Soga and Kaneko were temporarily removed from academic posts. Postwar economic hardship, declining public confidence, and competition from Japanese new religions further destabilized the Shinshū communities.[27]

Post-war Japan

[edit]The cumulative effect of the conflicts between the modernists and the conservatives was the development of contemporary Shin Buddhism shaped by modern ideas, institutional struggles, and broader socio-political forces. One lasting effect of the modernist reform efforts was the rise activism based around social and political problems, such as activism in support of burakumin.[33] Another impact was the reform of Ōtani Branch administration into a more democratic institution based on a representative assembly as well as limits on the head priest.[33]

In the postwar decades, a modernist faction within the Higashi Honganji administration gained institutional influence and reoriented propagation toward lay religious life, emphasizing personal spiritual awakening, introspection, and communal life. Reformers such as Kurube Shin’yū (1906-1998), and later Akegarasu Haya (1877-1954), sought to translate Kiyozawa’s Seishinshugi thought into practical religious programs, including retreats, district lectures, and lay education initiatives that eventually developed into the Dōbōkai movement of the 1960s. Modernist publications, such as the journal Shinjin, presented accounts of ordinary practitioners who discovered Buddhist meaning in daily life, illustrating a shift in emphasis from expectations of postmortem rebirth to recognition of awakening within present circumstances. Kiyozawa’s status rose through this sustained reinterpretation and promotion by his intellectual heirs.[27]

Despite the influence of these Shin modernists, traditional Shin interpretations continued to resist their doctrinal innovations, and tensions within Honganji communities persisted well after WWII, eventually leading to the Ohigashi schism.[31] According to Blum, while "Seishinshugi has been controversial from the start and remains so today," it was still extremely influential on all modern Shin thinkers, even those who rejected it.[30] In particular, the recasting of Amida’s Vow and birth in the Pure Land in existential and this-worldly terms generated both enthusiastic support and significant criticism. Some conservative critics saw these ideas as so unorthodox that they no longer saw people who espoused them as Shin Buddhists, and called for the resignation of any priests that defended it.[27][31]

The post-war period also saw a boom in scholarship on Shinran and Shin history, which includes the work of historians like Hattori Shisō and Ienaga Saburō. Much of these works discussed Shinran's relationship with the common people, how he had criticized powerful authorities, how later Shin Buddhism had moved away from his ideals and the implications of Shinran's thought for society.[33] Many popular books on Shinran were also written in the post-war era, more than for any other Japanese Buddhist founder, indicating a widespread interest.[33]

Recent scholarship on Shin Buddhism emphasizes the complexity of the modern transformation of Jōdo Shinshū as the product of complex interactions among teachers, administrators, political pressures, educational reforms, and the lived experiences of ordinary believers.[27] In contemporary times, Jōdo Shinshū remains one of the most widely followed forms of Buddhism in Japan. All ten schools of Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism commemorated the 750th memorial of their founder, Shinran, in 2011 in Kyoto.

Shin outside Japan

[edit]

During the 19th century, Japanese immigrants began arriving in Hawaii, the United States, Canada, Mexico and South America (especially in Brazil). Many immigrants to North America came from regions in which Jōdo Shinshū was predominant, and maintained their religious identity in their new country. The efforts of Nishi Honganji missionaries was important in the initial propagation of Shin Buddhism in the Western hemisphere. The first organized mission on American soil began when Rev. Dr. Shuya Sonoda and Rev. Kakuryō Nishijima arrived in San Francisco in 1899, forming the Bukkyo Seinenkai (Young Men’s Buddhist Association) to unite Japanese Buddhists in the new land. From this nucleus grew temples across the western states—in Sacramento, Fresno, Seattle, Oakland, San Jose, Portland, and Stockton—forming what came to be known as the Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist Mission of North America.

The mainland mission developed alongside, but independently of, the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii, which had been founded in the 1880s. In 1944, the organization was formally incorporated as the Buddhist Churches of America (BCA), now headquartered in San Francisco. Despite early struggles with anti-Japanese prejudice and the forced incarceration of its members during World War II, the BCA community persisted, maintaining Buddhist practice within the internment camps and later aiding in the resettlement of returning Japanese Americans through mutual support and shared temple spaces.

A parallel organization was also formed in Canada, the Buddhist Churches of Canada, now named the Jodo Shinshu Buddhist Temples of Canada (JSBTC). Furthermore, following extensive Japanese immigration to Brazil, a South America Hongwanji Mission was also established, which today maintains numerous temples in Brazil.

In the decades following the war, the BCA evolved from an immigrant religious association into a stable American Buddhist institution with over sixty affiliated temples and approximately twelve thousand members. The organization expanded its influence through education, founding the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Berkeley in 1949 as the first Buddhist seminary in the United States, now affiliated with the Graduate Theological Union.

Shin Buddhism grew in the U.S. through the efforts of numerous Japanese Shin Buddhists, Japanese Americans and even some American converts. Authors like D.T. Suzuki and Taitetsu Unno wrote some of the first English language books on Shin Buddhism. Western scholars and converts like Alfred Bloom and Roger Corless also contributed to the spread of Shin Buddhism.

The BCA has served as both a custodian of Jōdo Shinshū orthodoxy and a bridge between Japanese and Western religious cultures. It has sought to foster broader engagement with Buddhism in America through public festivals, youth and community programs, and interfaith activities, while also pioneering progressive stances such as the early endorsement of same-sex marriage and LGBTQ rights. Today, under leaders such as its first female president, Terri Omori, the BCA stands as the oldest and most established Buddhist organization in the continental United States.

Jōdo Shinshū continues to remain relatively unknown outside the ethnic community because of the history of Japanese American and Japanese-Canadian internment during World War II, which caused many Shin temples to focus on rebuilding the Japanese-American Shin Sangha rather than encourage outreach to non-Japanese. Today, many Shinshū temples outside Japan continue to have predominantly ethnic Japanese members, although interest in Buddhism and intermarriage contribute to a more diverse community. There are active Jōdo Shinshū Sanghas in the United Kingdom, such as Three Wheels Temple.[39]

During Taiwan's Japanese colonial era (1895–1945), Jōdo Shinshū built a temple complex in downtown Taipei.

Teaching

[edit]

Jōdo Shinshū doctrine and practice is based primarily on the works of Shinran, supplemented by the canonical Pure Land scriptures and the works of later figures like Rennyo. Shinran's teaching is closely based on the works of Chinese Pure Land Buddhist masters like Tanluan and Shandao, as well as on the teachings of Japanese Pure Land master Hōnen. For both Hōnen and Shinran, all conscious efforts towards achieving enlightenment through one's own efforts were defiled and deluded. Only the power of Amida Buddha, channeled in the nembutsu (a praise of Amida's name), could lead beings to Buddhahood in the Pure Land. Due to his awareness of human limitations, Shinran advocated reliance on tariki, or other power (他力)—the power of Amitābha (Japanese Amida) made manifest in his Original Vow—in order to attain liberation.

Shin Buddhism can therefore be understood as a "practiceless practice", for there are no specific acts to be performed such as there are in the "Path of Sages", which refers to all other Buddhist paths based accumulating merit and wisdom through our own efforts. In Shinran's own words, Shin Buddhism is considered the "Easy Path" because one is not compelled to perform many difficult, and often esoteric, practices in order to attain enlightenment through birth in the Pure Land. All that is needed to rely completely on the power of Amida's Original Vow (hongan).

Creed

[edit]The key worldview and creed of Shin Buddhism is often explained through a short text by Rennyo known as the Ryōgemon (領解文; "Statement of Conviction"). This work states:[40][41]

We abandon all indiscriminate religious practices and undertakings (zōgyō zasshu) and all mind of self-assertion (jiriki no kokoro), we rely with singleness of heart on the Tathāgata Amida in that matter of utmost importance to us now—to please save us in our next lifetime. We rejoice in knowing that our birth in the Pure Land is assured and our salvation established from the moment we rely [on the Buddha] with even a single nembutsu (ichinen), and that whenever we utter the Buddha's name thereafter it is an expression of gratitude and indebtedness to him. We gratefully acknowledge that for us to hear and understand this truth we are indebted to our founder and master [Shinran] for appearing in the world and to successive generations of religious teachers in our tradition for their profound encouragement. We shall henceforth abide by our established rules (okite) as long as we shall live. --Translation by Professor James C. Dobbins.

The Ryōgemon is still recited in modern-day Shinshu liturgy as summary of the Jōdo Shinshū teaching.

Amida and the Pure Land

[edit]

The central and ultimately only object of devotion and worship in Shin Buddhism is Amitābha Buddha (often called Amida in Japanese). According to Shin Buddhism, Amida is the original Buddha or fundamental Buddha (本佛, Jp: honbutsu), who is praised by all other Buddhas as supreme.[42] As per Shinran and Shandao, Amida Buddha is understood as a retribution-body (sambhogakāya) Buddha, the fruition of Dharmākara bodhisattva’s aeons-long bodhisattva career long ago, beginning with his making of the Original Vow, considered the heart of his compassionate power. However, Shinran also sees Amida as the direct compassionate manifestation of the formless, inconceivable Dharmakāya (the ultimate reality). In this view, from the ocean of suchness, a form arose as Bodhisattva Dharmākara, whose Great Vow became the heart of Buddhahood. Hence Amida is the “Dharmakāya as skillful means”, manifesting as unobstructed light covering the entire cosmos, which is Buddha wisdom itself.[43]

Shinran thus emphasizes the non-duality between the formless and form aspects of the Dharmakāya. The Original Buddha’s manifestation as Infinite Light is spontaneous, natural, and beyond all conceptual categories, and the Pure Land itself is ultimately not a spatial or temporal domain but the locus of awakening where ignorance is overturned. While conventional descriptions of jeweled lands and radiant bodies are upheld as compassionate means, their ultimate nature is vast, boundless, and inconceivable. For a person of true faith (shinjin), birth in the Pure Land entails the realization of the Dharmakāya and thus Nirvana. Nevertheless, at the conventional level Amida’s body, name, and land appear so that deluded beings may be instructed. Thus Shinran articulates a path that affirms Mahāyāna non-dualism at the ultimate level while retaining the functional dualities needed for conventional religious practice, which are nevertheless harmonized within the Buddha’s inconceivable wisdom and compassion.[44]

Later Shin figures like Zonkaku and Rennyo clarified the status of Amida Buddha further, arguing that Amida was the original Buddha (honbutsu), who was the source or ground (honji) out of which all other Buddhas and bodhisattvas emanated from.[45]

Shinjin and Nembutsu

[edit]

At the center of the Shin path is the attainment of shinjin in Amida Buddha's liberating other-power (tariki) and its expression through the nembutsu (the classic Pure Land devotional phrase "Namo Amida Butsu", Homage to Amida Buddha). Shinjin has been translated in different ways such as "faith" or "true entrusting", and it also often simply left untranslated.[46] Shinran places the nembutsu at the center of Pure Land practice but interprets it through the lens of shinjin, or true entrusting, which he identifies as the very core of the “true practice.” Following Tanluan and Shandao, he teaches that true faith entails a twofold awareness: recognition of one’s radical incapacity as a deluded being and trust in the liberating efficacy of Amida’s vows. All forms of self-power (jiriki), whether moral striving, meditative effort, attempts to accumulate merit, or any form of “calculation”, are all understood as impediments to true entrusting.[47] Only when a person fully realizes the futility of self-powered effort does the mind open to receive Amida’s gift of shinjin, a state that is simultaneously absolute trust and profound awareness of one’s defilements. This true entrusting is, for Shinran, the sole cause of birth in the Pure Land and equivalent to bodhicitta, buddha-nature, and even ultimate reality itself.[48]

Shinran holds that shinjin does not arise from human will or practice but is bestowed entirely by Amida as the working of the Original Vow. The nembutsu, the Name of Amida itself, is the efficient cause of liberation, manifesting in recitation, teaching, and subjective experience. In Shinran’s reading of the eighteenth vow of the Larger Sutra, the “one thought-moment” refers not to a temporal instant but to the “single mind” free of doubt, which is the Buddha’s own mind directed toward beings. Thus shinjin is the Buddha’s wisdom operating within the practitioner, and recitation of nembutsu becomes the spontaneous expression of that wisdom rather than a means of merit-making. Furthermore, since shinjin is a gift from Amida, it arises from jinen (自然, naturalness, spontaneous working of the Vow) and cannot be achieved through conscious effort but through a natural letting go. Thus, for Jōdo Shinshū practitioners, shinjin develops over time through "deep hearing" (monpo) of the Dharma and of Amida's call, which is the nembutsu itself. According to Shinran, "to hear" means "that sentient beings, having heard how the Buddha's Vow arose—its origin and fulfillment—are altogether free of doubt."[49] The nembutsu is thus understood as an act that expresses gratitude to Amitābha. It is not considered a "practice" in an instrumental sense which generates karmic merit. Instead, the nembutsu is an expression of faith and gratitude in the Buddha's infinite benevolence which is the source of the nembutsu itself.[50]

Due to the importance of faith, a key distinction in Shin Buddhism is between those who have attained settled faith from those who have not. The latter are advised to recite the nembutsu in gratitude and aspiration until shinjin arises naturally. Once true entrusting is received, the practitioner’s afflictions become one with the sea of Buddha wisdom, suffused by the working of the Original Vow despite the continuity of ordinary existence. The nembutsu then functions solely as an expression of gratitude and as the natural activity of Buddhahood within the devotee. Because all true practice and the attainment of Buddhahood arise exclusively from Amida’s power, Shinran’s system has been characterized as “absolute other-power,” a complete surrender of self-power in which all efforts are relinquished and the devotee is assured of birth in the Pure Land.[51] This distinguishes Shin Buddhism from other Pure Land schools including Jōdo-shū, which argues that one must make an effort to repeat the nembutsu extensively and that this is important for attaining birth in the Pure Land. It also contrasts with other Buddhist schools in China and Japan, where nembutsu recitation was part of more elaborate rituals and systems of practice.

The biggest doctrinal difference with the Jōdo-shū lies in the concept of "Other Power" (Tariki). The Jōdo-shū holds that if we have faith and recite the nembutsu accordingly, we will be saved. Thus they hold that the main cause of birth in the Pure Land is the nembutsu. However, Jōdo Shinshū holds the view that shinjin (true faith, the mind of trust) is the main cause of birth in the Pure Land, not the saying of the "Namu Amida Butsu". The nembutsu in Shin Buddhism is merely a manifestation of the true faith and an expression of gratitude in our being already saved by Amida. It is not an instrumental practice that causes our birth in the Pure Land.[52]

Realization and birth

[edit]Shin Buddhism follows Shinran's schema of the Pure Land to explain the differing results attained by nembutsu practitioners after death. Shin distinguishes three aspects of the Pure Land: (1) the "Borderland", where beings still burdened by doubt are temporarily separated from Amida; (2) the Transformed Land, perceptible to ordinary beings and attained by those who practice with partial reliance on self-power; (3) and the Truly Fulfilled Land, identified with Buddhahood itself, and realized only by those who attain shinjin. Although Shinran proclaims the Fulfilled Land where one instantly attains Buddhahood as the real goal of the eighteenth vow, all provisional lands are still seen as compassionate manifestations of the Original Vow.[53]

In another departure from more traditional Pure Land schools, Shinran advocated that birth in the Pure Land was settled in the midst of this life. At the moment one entrusts oneself to Amitābha, the “one thought-moment of shinjin”, one becomes "established in the stage of the truly settled." This is equivalent to attaining the stage of non-retrogression on the bodhisattva path.[54] This single, timeless event of shinjin fuses finite existence with the boundless reality of the Original Vow and opens the heart to the nirvanic realm that pervades all reality. Thus, Jōdo Shinshū teaches that the moment one attains shinjin ketsujō (the settled state of faith), where the desire to be saved through one's own power is completely extinguished, one's rebirth in the Ultimate Fulfilled Land of Utmost Bliss is completely assured. This is because since the mind of self-power rejects the working of Amida; when this self-power mind is abandoned, one is automatically embraced by Amida's vow power. Though still living amid samsaric conditions, the person of shinjin already abides in the Pure Land in their heart and is assured of immediate Buddhahood after death, thereby bypassing the long bodhisattva path envisioned in other systems.[55]

Despite this assurance, Shinran rejects the doctrine of attaining Buddhahood in this very life, insisting that full awakening occurs only upon birth in the Fulfilled Land.[56] Yet he affirms significant present-life benefits for those who entrust themselves to Amida. These include protection by devas and Buddhas, the transformation of evil into good, and the constant presence of Amida’s light, deep joy, gratitude, and compassion. [57] By virtue of the Original Vow’s power, practitioners become equal in status to beings such as Maitreya, possessing “one more birth” before Buddhahood, even though their Buddha-nature remains obscured until they reach the Pure Land. Thus, through the natural working (jinen) of Amida's infinite light, the deeply rooted karmic evil of countless rebirths are transformed into goodness and compassion. Shin stays within the Mahayana tradition's understanding of emptiness and understands that saṃsāra and nirvāṇa are not ultimately separate. As such, this state of shinjin is a state of being open to the working of Buddhahood while also remaining a foolish sentient being. According to Shinran, the spiritual transformation which occurs subsequent to the attainment of shinjin happens naturally, "without the practitioner having calculated it in any way".[58]

Evil

[edit]In Shinran’s account, the salvific activity of Amida operates beyond the duality of good and evil. Because Amida’s Vow was established precisely to liberate beings overwhelmed by the afflictions, virtuous actions have no direct role in the attainment of birth in the Pure Land. Faith alone constitutes the sole condition. On this basis Shinran articulates the principle that the very persons most burdened by evil are the primary objects of the Vow (J: akunin shōki), for their recognition of their own incapacity disposes them to relinquish self-power and rely wholly on Amida. Those who regard themselves as virtuous, by contrast, tend to depend on their own merit and thereby fail to entrust themselves fully, placing themselves outside the central intention of the Vow.[59]

Amida's infinite compassion means that even those guilty of the gravest offenses are embraced in the Pure Land. It also means that the virtuous cannot augment or constrain the operation of the Vow. This radical position often generated misinterpretations among some followers, who advanced the view of “licensed evil,” claiming that deliberate wrongdoing was permissible or even desirable because salvation was assured. Shinran rejected this as a distortion of Other Power faith, arguing that intentional wrongdoing in order to provoke Amida’s compassion is itself an expression of self-power and a fundamental misunderstanding of the Vow’s aim.[60]

Shinran also held that since the world had entered the Age of Dharma Decline, the traditional Buddhist clerical precepts no longer function as effective means for practice, for the path of sages depending on rigorous moral and meditative discipline is no longer viable for most beings. In this situation, one finds practitioners who are “monks in name only,” and Shinran identified himself with this condition as one who is "neither monk nor layman" yet still follows the Buddha’s way.[61] Although sometimes interpreted as eliminating ethics altogether, Shinran maintained that the nembutsu naturally generates an aspiration to turn away from evil. Through the transformative influence of the Vow, the afflictions of beings are illuminated, softened, and gradually shaped by compassion, though not eradicated in this life.[62] Because of this, Shinran sets forth no fixed set of moral injunctions nor any expectation of perfection in the present existence. Instead, he teaches that assurance of future Buddhahood coexists with the persistence of the afflictions, which are themselves taken up by the working of Other Power. The Shin path therefore involves recognizing one’s ethical limitations, abandoning self-power, and accepting one’s deluded condition while entrusting oneself to Amida.[63]

Customs and practices

[edit]

The central practice of Shin Buddhism is the simple recitation of the nembutsu ("Namo Amida Butsu") with faith and gratitude. This may be done at temples, at personal home shrines (butsudans) and in daily life.[64] It is customary to hold traditional beads when reciting the nembutsu, as well as to bow before a Buddhist shrine (butsudan) and to place one hands together in gassho.[64] Shin Buddhist mindfulness beads (nenjus) have a unique knot on the right parent bead is called the “Rennyo Knot”. The knot designs on the counting beads prevent the counting of rounds, which expresses the view that it is faith, not the number of nembutsu recitations, that lead one to the Pure Land.

Shin Buddhism also encourages the installation of a honzon (main object of worship, often a simple inscription of "Namu Amida Butsu," a painted image, or a wooden statue of Amida Buddha) inside a Buddhist altar (butsudan) in every household.[64] Butsudans are traditionally decorated with other objects such as a flower vase, incense burner and lanters.[64] There are specific traditional rules and requirements for these ritual objects. As the adornments are modeled after the head temples of each sub-sect, the shape and ritual implements differ by sub-sect. In Shin Buddhism, the honzon enshrined and adorned within the butsudan is seen as a "miniature temple" invited into each home, and it is not meant to be used as an ancestral altar with pictures of the deceased (as is common in other traditions).

Prostration (gotaitochi) before a butsudan is also a traditional practice.[64] Shin Buddhists may also offer incense, flowers and other offerings in front of the butsudan.[64] Shin Buddhists in Japan traditionally use the Gold Lacquered type of Butsudan.[64]

Other Jōdo Shinshū religious practices include the recitation of Shin Buddhist liturgy, which includes Pure Land Sutras, hymns like the Shōshinge, the Sanjō Wasan and Nagarjuna's Junirai (Twelve Praises [to Amida]), along with other texts.[65][66][67] The reading and study of Pure Land scriptures and the works of Shinran are also an important practice for some Shin Buddhists.

According to Jørn Borup, "while not being part of orthodox Shin Buddhism, in recent years meditation has been discussed and accepted at official levels."[68] Meditation in Shin Buddhism (sometimes called seiza) was promoted by modern Shin figures like Kaneko Daiei, Yoshikiyo Hachiya, Shūgaku Yamabe, and Susumu Yamaguchi. It is often presented as a way to calm the mind so that one can better listen to the Dharma without calculation (hakarai).[69]

Clergy

[edit]

The most significant difference between Jōdo Shinshū and other Buddhist schools (including Jōdo-shū) is its thoroughgoing non-observance of Buddhist clerical precepts, allowing its clergy to eat meat, drink alcohol and have families.[70] Until the Meiji period (1868–1912), Shin was the only Buddhist sect where clerical marriage was openly permitted. This lack of clerical precepts originates from Shinran, who inherited from his teacher Hōnen the teaching that the nembutsu can save everyone, even those who fall outside ethical norms. However, unlike Shinran, Hōnen affirmed the importance of keeping clerical precepts, and this issue remains a significant difference between Shin Buddhism and Jodo-shu.[71]

Prior to exile, Shinran had his monastic status stripped away, became "neither monk nor layman," officially married, and had children. Shinran held that the decline of precept keeping was a normal feature of the Age of Dharma Decline, and that birth in the Pure Land was not hindered by the lack of precepts.[71] Shin Buddhist clergy follow this example and do not take official precepts like other Buddhist schools, not even the bodhisattva precepts. Nevertheless, they still undergo a process of ordination (tokudo), where they cut their hair, receive monastic style robes and recite statements of faith.[72] Furthermore, Shin ministers (J: 住職 jūshoku) receive formal education in the doctrines and practices of Shin Buddhism in official universities, just like the priests and monks of other Buddhist schools.[68] With the rise of modern Shin education, the wives of temple priests (bonmori, "temple guardians") are also often educated as well and can perform many of the same roles.[73]

Another key difference between Shin Buddhism and other forms of Japanese Buddhism lies in the role of the teacher and lineage. The teacher is an important figure in Shin, since it is they who introduce a person to the Pure Land path, provide guidance and help resolve doubts. Nevertheless, Shinran rejected the traditional view of formal Buddhist "master-disciple" lineage as well as any concept of Dharma transmission, famously writing that "I do not have a single disciple".[74] Instead, Shinran, and thus Shin Buddhism as a whole, emphasize the central role of Amida Buddha as the main source of spiritual transformation. The teacher acts merely as a secondary facilitator, not as the source of transmission and transformation. This stands in sharp contrast to Zen and Esoteric schools like Shingon, where the Zen master or Vajracharya is the main source of the transmission of wisdom or esoteric knowledge.[74] According to Dobbins, this view has clear implications in Shin Buddhism, since in Shin the relationship between teacher and student "had to be subordinated to the primary religious concern, the personal encounter with Amida's vow."[75]

Temple activities and customs

[edit]

Shin Buddhist temples and congregations perform various activities throughout the year, including religious services, reading scripture, social activities, propagation of the teachings (fukyō), lectures (hōwa), yearly celebrations (like Obon), memorial rites (hōyō), and a variety of rites of passage.[68]

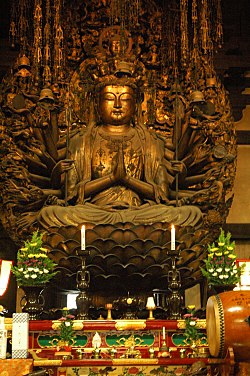

Since Jōdo Shinshū teaches that all people can be reborn in the Pure Land by entrusting themselves solely to Amida Buddha's working, it does not adhere to many religious rituals and customs found in other schools (such as elaborate death ceremonies, and distribution of talismans or ofuda), instead emphasizing the nembutsu as an expression of gratitude and the listening to the Dharma. Generally speaking, Shin Buddhist temples do not contain shrines for deities other than Amida Buddha and perhaps select bodhisattvas such as Kannon (manifested as Prince Shōtoku for example) or Shinran. Kami worship and shrines are thus not usually part of Shin Buddhist temples, as Shinran clearly rejected worship of these deities and promoted exclusive veneration of Amida.[45][76][67]

Later figures like Zonkaku and Rennyo argued that all Buddhist deities, bodhisattvas and kami were manifestations of Amida Buddha, who was their original ground and the original Buddha. As such, by worshipping Amida, one was protected by all these deities without having to actively worship them directly.[45]

Shinran also rejected other common practices upheld by other schools of Japanese Buddhism, which he associated with self-powered efforts to gain worldly benefits and avert calamities. These included: "the propitiation of ghosts and evil spirits; divination of good and evil; belief in auspicious days, times, and directions; and observance of taboos (monoimi)."[76]

Head temples (honzan) of Shin Buddhism always have a Founder's Hall (Goeidō) housing the true image (shin'ei) of the founder Shinran, separate from the Main Hall (Hondō) which houses the honzon representing Amida Buddha. Shin Buddhist temple architecture also has other characteristics not seen in other schools, such as a large outer sanctuary (gejin) compared to the inner sanctuary (naijin).

Shin Buddhist temples also observe traditional Japanese Buddhist holidays, like Obon.[64]

Funerary services and memorials

[edit]All sub-sects of Jōdo Shinshū also perform a memorial service called the Hōonkō (報恩講) on the anniversary of Shinran's death, which focuses on gratitude and community by repaying the benevolence of Shinran and Amida through scriptural readings, chanting and lectures.[67] This service is considered the most important event of the Shin liturgical calendar, though the specific date differs among sub-sects.[77][78]

Apart from this, personal memorials services, funerals and other rites for the deceased are performed year round, such as ritual recitation of sutras for the dead (a rite called eitai-kyō).[67] Another official service performed by Shin clergy is the "pillow service". This involves the recitation of Pure Land sutras for a dying person, giving them an opportunity to hear the Dharma one last time.[64]

Unlike in other Buddhist sects, Shin memorial services are not considered to aid in the good rebirth of the deceased. Rather, these memorial services are considered to be opportunities for the living to remember the dead in gratitude and to share and listen to the Dharma.[79] Shin funerary and deathbed rites are understood differently than those in other Japanese Pure Land traditions, which see the dying process as a key moment where one could attain birth in the Pure Land or fail to do so. Funerary rites meant to assure birth in the Pure Land were common during the Kamakura period, and included extensive periods of chanting by numerous monastics and various ritual objects. Shinran rejected the efficacy of all these rites, seeing them as self-powered efforts. For Shinran, only faith (shinjin) in Amida leads to the Pure Land, not extensive rituals or even simple chanting on behalf of others. Thus he is quoted in the Tannishō as stating "I have never said the nenbutsu even once for the repose of my father and mother."[67] Shinran also requested not to be buried in a grave, rather that his body be placed in a river to feed the animals.[67]

Because of this dimension of Shinran's teaching, while the Shin tradition did develop a system of funerary rites as all Japanese Buddhist schools, there was much doctrinal disagreement and debate regarding their orthodoxy and their application.[67] When funerary rites came to be widely accepted, Shin clerics did not interpret these rites in an instrumentalist fashion as rites that could cause the deceased to attain birth in the Pure Land through the efforts of the officiants. Instead, they were generally interpreted in line with Shin orthodoxy as rites that relied on other-power. The rites could also be understood as ways of calling on the deceased for aid, since they had presumably entered the Pure Land and become Buddhas or bodhisattvas. This relies on the second interpretation of merit transference (ekō) as taught by Pure Land patriarchs like Tanluan, which refers to transfering merit to all sentient beings after having attained birth in the Pure Land. This contrasts with performing a rite so as to make merit that we can then transfer it the deceased and thus help them attain birth in the Pure Land.[67]

Scriptures

[edit]

The main sacred scriptures studied in Jōdo Shinshū are collected in the Jōdo Shinshū Seiten. The key works are the following:[80]

- The Sutra of Immeasurable Life

- The Amida Sutra

- The Contemplation Sutra

- Nāgārjuna's Commentary on the Ten Stages Sūtra (Daśabhūmivibhāṣā-śāstra)

- Nāgārjuna's Twelve Adorations (Jūnirai)

- Vasubandhu's Discourse on the Pure Land (Jōdo Ron)

- Tanluan's Commentary on Discourse on the Pure Land

- Tanluan's Gathā in Praise of Amida (San Amida Butsu Ge)

- Daochuo's Collection on Peace and Bliss (Anraku-shū)

- Shandao's Commentary on the Contemplation Sūtra (Kangyōsho) along with his other works

- Genshin's Essentials of Birth in the Pure Land (Ōjōyōshū)

- Hōnen's Passages on the Selection of the Nembutsu in the Original Vow (Senchakushū)

- Hōnen's General Meaning of the Three Pure Land Sūtras (Sanbukkyō Taii)

- Hōnen's Letters

- Shinran's Complete Works (especially the Kyōgyōshinshō)

- Letters of Eshinni (Eshinni Shōsoku)

- Yuien's Tannishō

- Anjin Ketsujō Shō

- Seikaku's Essentials of Faith Alone (Yuishinshō)

- Ryūkan's On Once Calling and Many Calling (Ichinen Tanen Funbetsu no Koto)

- Ryūkan's On Self-power and Other-power (Jiriki Tariki no Koto)

Many of these texts are available in English translation as part of the Shin Buddhism Translation Series of Nishi Hongwanji's International Department.[81]

The Honganji sect also maintains collections of specifically Honganji Shin masters, such as:[80]

- Kakunyo's writings, such as Record of the Transmission of the Master’s Life (Godenshō) and Treatise on Upholding and Maintaining [the Teaching] (Shūji-shō)

- Zonkaku's works, such as Essentials of the True Pure Land Teaching (Jōdo Shin’yō-shō) and Treatise on the Recitation of the Name (Jimyō-shō)

- Rennyō's writings, including his letters, commentaries on the Shōshinge, poems, etc.

Tannishō

[edit]The Tannishō (Record in Lament of Divergences) is a 13th-century book of recorded sayings attributed to Shinran, transcribed with commentary by Yuien-bo, a disciple of Shinran. While it is a short text, it is very popular because practitioners see Shinran in a more informal setting. For centuries, the text was almost unknown to the majority of Shin Buddhists. In the 15th century, Rennyo, Shinran's descendant, wrote of it, "This writing is an important one in our tradition. It should not be indiscriminately shown to anyone who lacks the past karmic good." Rennyo Shonin's personal copy of the Tannishō is the earliest extant copy. Kiyozawa Manshi (1863–1903) revitalized interest in the Tannishō, which indirectly helped to bring about the Ohigashi schism of 1962.[8]

In Japanese culture

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Japanese Buddhism |

|---|

|

Earlier schools of Buddhism that came to Japan, including Tendai and Shingon Buddhism, gained acceptance because of honji suijaku practices. For example, a kami could be seen as a manifestation of a bodhisattva. It is common even to this day to have Shinto shrines within the grounds of Buddhist temples.

By contrast, Shinran had distanced Jōdo Shinshū from Shinto because he believed that many Shinto practices contradicted the notion of reliance on Amitābha. However, Shinran taught that his followers should still continue to worship and express gratitude to kami, other buddhas, and bodhisattvas despite the fact that Amitābha should be the primary buddha that Pure Land believers focus on.[82] Furthermore, under the influence of Rennyo and other priests, Jōdo Shinshū later fully accepted honji suijaku beliefs and the concept of kami as manifestations of Amida Buddha and other buddhas and bodhisattvas.[83]

Jōdo Shinshū traditionally had an uneasy relationship with other Buddhist schools because it discouraged the majority of traditional Buddhist practices except for the nembutsu. Relations were particularly hostile between the Jōdo Shinshū and Nichiren Buddhism. On the other hand, newer Buddhist schools in Japan, such as Zen, tended to have a more positive relationship and occasionally shared practices, although this is still controversial. In popular lore, Rennyo, the 8th Head Priest of the Hongan-ji sect, was good friends with the famous Zen master Ikkyū.

Jōdo Shinshū drew much of its support from lower social classes in Japan who could not devote the time or education to other esoteric Buddhist practices or merit-making activities.

Shin Patriarchs

[edit]

The "Seven Patriarchs of Jōdo Shinshū" are seven Buddhist monks venerated in the development of Pure Land Buddhism as summarized in the Jōdo Shinshū hymn Shōshinge. Shinran quoted the writings and commentaries of the Patriarchs in his major work, the Kyōgyōshinshō, to bolster his teachings.

The Seven Patriarchs, in chronological order, and their contributions are:[84][85][86][87]

| Name | Dates | Japanese name | Country of origin | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nagarjuna | 150–250 | Ryūju (龍樹) | India | Indian master and Madhyamaka philosopher who presents Pure Land as the "easy path" in his Ten Stages Treatise. |

| Vasubandhu | c. 4th century | Tenjin (天親) or Seshin (世親) | India | Wrote the Discourse on the Pure Land explaining Pure Land practice. |

| Tanluan | 476–542(?) | Donran (曇鸞) | China | Known for his commentary on Vasubandhu's Discourse, where he develops the key distinction between self-power and other-power. |

| Daochuo | 562–645 | Dōshaku (道綽) | China | Promoted the superiority of the "easy path" of Pure Land over the "path of the sages", which he held was no longer efficacious since the world had entered the "last days of the Dharma". |

| Shandao | 613–681 | Zendō (善導) | China | Wrote an influential commentary to the Contemplation Sutra where he discusses the threefold mind of faith, and argues that the verbal recitation of Amida's name should be the main practice in Pure Land Buddhism. |

| Genshin | 942–1017 | Genshin (源信) | Japan | Tendai teacher who popularized Pure Land practices as the most effective method for the era of Dharma decline (mappo) in his extensive Ōjōyōshū. |

| Hōnen | 1133–1212 | Hōnen (法然) | Japan | Popularised the exclusive recitation of the nembutsu in order to attain rebirth in the Pure Land and argued we should set aside other practices in favor of nembutsu. |

In Jōdo Shinshū temples, the seven masters are usually collectively enshrined on the far left.

Branch lineages

[edit]- Jōdo Shinshū Hongwanji School (Nishi Hongwan-ji)

- Jōdo Shinshū Higashi Honganji School (Higashi Hongan-ji)

- Shinshū Ōtani School

- Shinshū Chōsei School (Chōsei-ji)

- Shinshū Takada School (Senju-ji)

- Shinshū Kita Honganji School (Kitahongan-ji)

- Shinshū Bukkōji School (Bukkō-ji)

- Shinshū Kōshō School (Kōshō-ji)

- Shinshū Kibe School (Kinshoku-ji)

- Shinshū Izumoji School (Izumo-ji)

- Shinshū Jōkōji School (Jōshō-ji)

- Shinshū Jōshōji School (Jōshō-ji)

- Shinshū Sanmonto School (Senjō-ji)

- Montoshūichimi School (Kitami-ji)

- Kayakabe Teaching (Kayakabe-kyō) - An esoteric branch of Jōdo Shinshū

Major holidays

[edit]The following holidays are typically observed in Jōdo Shinshū temples:[88]

| Holiday | Japanese name | Date |

|---|---|---|

| New Year's Day Service | Gantan'e | January 1 |

| Memorial Service for Shinran | Hōonkō | November 28, or January 9–16 |

| Spring Equinox | Higan | March 17–23 |

| Buddha's Birthday | Hanamatsuri | April 8 |

| Birthday of Shinran | Gotan'e | May 20–21 |

| Bon Festival | Urabon'e | around August 15, based on solar calendar |

| Autumnal Equinox | Higan | September 20–26 |

| Bodhi Day | Jōdō'e | December 8 |

| New Year's Eve Service | Joya'e | December 31 |

Major modern Shin figures

[edit]- Nanjō Bun'yū (1848–1927)

- Saichi Asahara (1850–1932)

- Kasahara Kenju (1852–1883)

- Kiyozawa Manshi (1863–1903)

- Jokan Chikazumi (1870–1941)

- Eikichi Ikeyama (1873–1938)

- Soga Ryōjin (1875–1971)

- Ōtani Kōzui (1876–1948)

- Akegarasu Haya (1877–1954)

- Kaneko Daiei (1881–1976)

- Zuiken Saizo Inagaki (1885–1981)

- Takeko Kujō (1887–1928)

- William Montgomery McGovern (1897–1964)

- Rijin Yasuda (1900–1982)

- Gyomay Kubose (1905–2000)

- Shuichi Maida (1906–1967)

- Harold Stewart (1916–1995)

- Kenryu Takashi Tsuji (1919–2004)

- Alfred Bloom (1926–2017)

- Zuio Hisao Inagaki (1929–present)

- Shojun Bando (1932–2004)

- Taitetsu Unno (1935–2014)

- Eiken Kobai (1941–present)

- Dennis Hirota (1946–present)

- Kenneth K. Tanaka (1947–present)

- Marvin Harada (1953–present)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Essentials of Jodo Shinshu from the Nishi Honganji website". Retrieved 2016-02-25.

- ^ Jeff Wilson, Mourning the Unborn Dead: A Buddhist Ritual Comes to America (Oxford University Press, 2009), pp. 21, 34.

- ^ Amstutz, G. (2020). "Steadied Ambiguity: the Afterlife in “Popular” Shin Buddhism". In Critical Readings on Pure Land Buddhism in Japan (Volume 2). Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004401518_020

- ^ a b Dobbins (1989), p. 2.

- ^ Bloom, Alfred. “The Life of Shinran Shonin: The Journey to Self-Acceptance.” Numen, vol. 15, no. 1, 1968, pp. 1–62. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3269618. Accessed 31 Oct. 2025.

- ^ Ducor, 2021, p. 31.

- ^ "JODO SHU English". Jodo.org. Archived from the original on 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ^ a b c d Popular Buddhism in Japan: Shin Buddhist Religion and Culture by Esben Andreasen / University of Hawaii Press 1998, ISBN 0-8248-2028-2.

- ^ Ducor, 2021, p. 36.

- ^ Bloom, Alfred. “The Life of Shinran Shonin: The Journey to Self-Acceptance.” Numen, vol. 15, no. 1, 1968, pp. 1–62. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3269618. Accessed 31 Oct. 2025.

- ^ Dobbins (1989), p. 63.

- ^ Dobbins (1989), pp. 63-64.

- ^ a b Ducor, 2021, p. 36.

- ^ Dobbins (1989), pp. 67-68

- ^ Dobbins (1989), p. 68

- ^ Ducor, 2021, p. 36.

- ^ Dobbins (1989), pp. 47-51

- ^ Dobbins (1989), p. 53.

- ^ a b Ducor, Jérôme: Shinran and Pure Land Buddhism, p. 41. Jodo Shinshu International Office, 2021 (ISBN 0999711822)

- ^ Fukagawa, Nobuhiro (1984). "A Study of Kakunyo's Teachings: his Shuji-sho". Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies (indogaku Bukkyogaku Kenkyu). 32 (2): 586–591. doi:10.4259/ibk.32.586.

- ^ Callahan, C. (2016). Recognizing the founder, seeing Amida Buddha: Kakunyo’s Hōon kōshiki. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 43(1), 177-205. https://doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.43.1.2016.177-205

- ^ Dobbins (1989), p. 79

- ^ 呂靖聖子. Understanding the Sacred Path Teachings in Zonkaku's "Hosen-sha": Focusing on an Examination of the "Kegon School" Section (存覚撰 [ 歩 船 紗 ] における聖道門理解 ll [華厳宗] 項の検討を中心に), Ryūkoku University

- ^ Moriarty, Elisabeth (1976). Nembutsu Odori, Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 7–16.