Elizabeth Báthory

Elizabeth Báthory | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Báthori Erzsébet 7 August 1560 |

| Died | 21 August 1614 (aged 54) |

| Other names | Bloody Countess[1] |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Family | Báthory |

Countess Elizabeth Báthory of Ecsed (Hungarian: Báthori Erzsébet, pronounced [ˈbaːtori ˈɛrʒeːbɛt]; Slovak: Alžbeta Bátoriová, 7 August 1560 – 21 August 1614)[2] was a Hungarian noblewoman and serial killer from the powerful House of Báthory, who owned land in the Kingdom of Hungary (now Slovakia). Báthory and four of her servants were accused of torturing and killing hundreds of girls and women from 1590 to 1610.[3] Bathory and her cohorts were charged for 80 counts of murder and were convicted.[4][5] Her servants were put on trial and convicted. The servants were executed, whereas Báthory was imprisoned within the Castle of Csejte (Čachtice) until she died in her sleep in 1614.[6][7]

The charges levelled against Báthory have been described by several historians as a witch-hunt.[8][9] Other writers, such as Michael Farin in 1989, have said that the accusations against Báthory were supported by testimony from more than 300 individuals, some of whom described physical evidence and the presence of mutilated dead, dying and imprisoned girls found at the time of her arrest.[10] Recent scholarship suggests that the accusations were a spectacle to destroy her family's influence in the region, which was considered a threat to the political interests of her neighbours, including the Habsburg empire.[11]

Stories about Báthory quickly became part of national folklore.[12] Legends describing her vampiric tendencies, such as the tale that she bathed in the blood of virgins to retain her youth, were based on rumours and only recorded as supposedly factual over a century after her death. Although these stories were repeated by at least three historians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, they are considered unreliable by modern historians.[13] Some insist that Elizabeth's story inspired Bram Stoker's novel Dracula (1897),[14] although Stoker's notes on the novel provided no direct evidence to support this hypothesis.[15] Nicknames and literary epithets attributed to her include Blood Countess and Countess Dracula.

There are important flaws regarding modern scholarships attempt to paint Elizabeth Bathory as a victim of a "witch hunt". Firstly, Elizabeth was charged predominantly with murder and torture, not witchcraft.[16] Secondly, on the night of the raid, Elizabeth Bathory was taken into custody along with her four accomplices.[5] Elizabeth had accused two reverends and one pastor for the reason of her arrest,[17] after a long conversation where Bathory attempted to blame her accomplices for the dead bodies being found.[17] She added this statement after Pastor Barosius had asked her why she did not stop her accomplices from committing the tortures and murders. She said, "I did it ... Because even I myself was afraid of them".[17] This statement was confessed by Bathory herself and was not done under torture.

Critically, there were a handful of individuals who provided first-hand accounts of Bathory's crimes at the trial. Three of these individuals included Jakab Szivassy, Gergely Paztory, and Benedek Deseo.[18] Deseo was the head of "The Lord's staff" at Castle Cjesthe and was responsible for operations at the castle.[19] Since Deseo and Szivassy were around Bathory the most, they gave the most detailed confessions of what they witnessed at their time of service at Castle Cjesthe. It is important to note that these three men were not tortured into confessions, unlike Bathory's accomplices (Llona, Janos, Dorrthea, etc.). After Deseo was sworn in, he testified that Bathory "took a shoemaker's daughter named 'Illonka',[20] stripped her naked and, in this way began to cruelly torment her by taking a knife, and beginning with the fingers, shoved the knife into both arms up the arms, then flogging her over again, then took a burning candle to her and burned her skin, and continued to torment her until she put an end to her life".[21] He also testified that Bathory would "stick a sewing needle in her victims arms and use it to cut her way up the arm of a girl who could not 'sew'."[22]

Gergely Paztory was a court judge at Castle Sarvar for Elizabeth Bathory and was forty years old when he was sworn in and testified.[23] He testified that a "young woman from Bratislava named Modl accompanied Bathory and Paztory on a trip to Fuzer".[23] He continued, "The Lady Bathory forced her to dress up and act like a young girl, Modl pleaded for forgiveness as she could not act like a young girl since she is already married and has a child".[24] Following this, in Jakab Szivassy's testimony, Jakab added that the "young woman called Modl, since she did not want to be a girl, Bathory had cut out her flesh and roasted it".[24] These testimonies were collected by Mozes Cziraky and was published on December 14, 1611, in his report on the orders of King Matthias II.[20]

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]

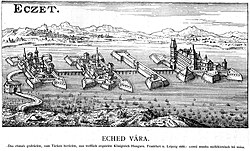

Elizabeth was born in 1560 on a family estate in Nyírbátor, Royal Hungary, and spent her childhood at Ecsed Castle. Her father was Baron George VI Báthory (d. 1570), of the Ecsed branch of the family, brother of Andrew Bonaventura Báthory (d. 1566), who had been ruling Voivode of Transylvania. Her mother was Baroness Anna Báthory of Somlyó (1537–1570), member of the other line of the Báthory family, daughter of Stephen Báthory of Somlyó, Palatine of Hungary. Through her mother, Elizabeth was the niece of Stephen Báthory (1533–1586), Prince of Transylvania, who became the ruler of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania.[25] She had several siblings; her older brother Stephen (1555–1605) served as a Judge Royal of Hungary.[11]

Báthory was raised a Calvinist Protestant,[7] and learned Latin, German, Hungarian, and Greek as a young woman.[3][26] Born into a privileged noble family, she was endowed with wealth, education, and a prominent social rank.[25] A proposal made by some sources[who?] in order to explain Báthory's cruelty later in her life is that she was trained by her family to be cruel.[27]

As a child, Báthory had multiple seizures that may have been caused by epilepsy.[26] At the time, symptoms relating to epilepsy were diagnosed as falling sickness and treatments included rubbing blood of a non-sufferer on the lips of an epileptic or giving the epileptic a mix of a non-sufferer's blood and piece of skull as their episode ended.[28][original research?]

At the age of 13, before her first marriage, Báthory allegedly gave birth to a child.[27] The child, said to have been fathered by a peasant boy, was supposedly given away to a local woman who was trusted by the Báthory family.[27] The woman was paid for her actions, and the child was taken to Wallachia.[27] Evidence[example needed] of this pregnancy came up long after Elizabeth's death, through rumours spread by peasants; therefore, the validity of the rumour is often disputed.

Marriage and land ownership

[edit]

In 1573, Báthory was impregnated by a peasant lover and was hidden away to bear the child in secret.[29]

In 1574,[11] Báthory was engaged to Count Ferenc Nádasdy, a member of the Nadasdy family. It was a political arrangement within the circles of the aristocracy. Nádasdy was the son of Baron Tamás Nádasdy de Nádasd et Fogarasföld (1498–1562) and his wife, Orsolya Kanizsai (1523–1571).

On 8 May 1575, Báthory and Nádasdy were married at the palace of Varannó (today Vranov nad Topľou, Slovakia).[11] The marriage resulted in combined land ownership in both Transylvania and the Kingdom of Hungary.[11]

Nádasdy's wedding gift to Báthory was his household in the Castle of Csejte (Čachtice), situated in the Little Carpathians near Vág-Ujhely and Trencsén (present-day Nové Mesto nad Váhom and Trenčín, Slovakia).[11] At the time, King Maximilian II owned the castle, but made Ferenc's mother, Orsolya Kanizsai, official steward in 1569. Nádasdy finally bought the castle in 1602 from Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, but during his constant military campaign, Elizabeth maintained the castle in his absence, along with the Csejte country house and seventeen adjacent villages.[30]

After the wedding, the couple lived in Nadasdy's castle at Sárvár.[11]

In 1578, three years into their marriage, Nádasdy became the chief commander of Hungarian troops, leading them to war against the Ottomans.[citation needed] Báthory managed business affairs and the family's multiple estates during the war. This role usually included responsibility for the Hungarian and Slovak people, providing medical care during the Long War (1593–1606), and Báthory was charged with the defence of her husband's estates, which lay on the route to Vienna. The threat of attack was significant, for the village of Csejte had previously been plundered by the Ottomans while Sárvár, located near the border that divided Royal Hungary and Ottoman-occupied Hungary, was in even greater danger.

Báthory's daughter, Anna Nádasdy, was born in 1585 and was later to become the wife of Nikola VI Zrinski. Báthory's other known children include Orsolya (Orsika) Nádasdy (1590–unknown) who would later become the wife of István II Benyó; Katalin (Kata or Katherina) Nádasdy (1594-unknown); András Nádasdy (1596–1603); and Pál (Paul) Nádasdy (1598–1650), father of Franz III Nádasdy, who was one of the leaders of the Magnate conspiracy against Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I.[citation needed] Some chronicles also indicate that the couple had another son, named Miklós Nádasdy, who married Zsuzsanna Zrinski. However, this cannot be confirmed, and it could be that he was simply a cousin or died young, as he is not named in Báthory's will from 1610. György Nádasdy is also supposedly the name of one of the deceased Nádasdy infants, but this cannot be confirmed. All of Elizabeth's children were cared for by governesses, as Báthory herself had been.[citation needed]

Ferenc Nádasdy died on 4 January 1604 at the age of 48. Although the exact nature of the illness which led to his death is unknown, it seems to have started in 1601 and initially caused debilitating pain in his legs. From that time, he never fully recovered, and in 1603 became permanently disabled.[citation needed] He had been married to Báthory for 29 years. Before dying, Nádasdy entrusted his heirs and widow to György Thurzó, who would eventually lead the investigation into Báthory's crimes.[citation needed]

Accusations

[edit]

Between 1602 and 1604, after rumours of Báthory's atrocities had spread throughout the kingdom, Lutheran minister István Magyari made complaints against her, both publicly and at the court in Vienna.[31] In 1610, Matthias II assigned György Thurzó,the devoutly Lutheran Palatine of Hungary, to investigate. Thurzó ordered two notaries, András Keresztúry and Mózes Cziráky,[32] to collect evidence in March 1610.[33] By October 1610 they had collected 52 witness statements;[32] by 1611, that number had risen to over 300.

Tamás Nyereghjárto was 35 years old, when he was sworn in and interrogated in the town of Beckov.[34] He stated that he saw a girl in Újhely who was being medically treated on because the flesh on her right hand between the fingers and the arm was torn out and the tendon was destroyed.[34] The wife of Janós Kun, named Katalin, (Janós Kun was the Provisor of Franciscus Magochy in Beckov, and was 50 years old)[35] Katalin who was 36 years old testified that she had also seen this girl in Újhely, and testified similarly to Tamás,[35] but added that the flesh had also been cut out between the victims shoulders, and that the right hand of this girl was "completely destroyed".[35] Then, Martinus Zamechnyk, who was 50 years old, testified that he had asked this Girl from Újhely "Who did that to your hand", the girl had replied that "The Lady Widow Nadasdy had done it"(Elizabeth Bathory).[36] This testimony was taken by András of Keresztúr, and was published on July 28, 1611, on the orders of King Matthias II.[37]

According to one of her accomplices, (Dorrthea Szentes), Bathory would stick needles into the fingers of some of her victims.[38] After she did this, Bathory would comment: "If it hurts the whore, then she can pull it out". However, Szentes added that if the girl removed the needle, Bathory would then cut off the finger with a knife.[38]

During the trial, many atrocities were said to have occurred in many of Bathory's castles.[39][40] These atrocities usually included: Severe beatings with cudgels, needles inserted into lips, arms, shoulders, and fingernails.[41] Flesh cut out from the buttocks and from between the shoulders, and then roasted.[41] Red hot pokers and irons used to scorch the arms and abdomen of the victims, knives plunged into arms and feet, fingers cut off with scissors and sheers,[41] and girls made to stand naked in the winter cold and then doused with water till they froze to death.[41]

Nobleman Martinus Chanady who lived in the town of Beckov was 48 years old when he was sworn in and interrogated.[42] He testified that himself and Janós Belanczky had visited the Lady Widow Nadasdy in Beckov so that Janós could get his sister back from Bathory.[42] Bathory had refused to give Janós' sister back when they asked. Janós then demanded that he at least see her, after waiting for nearly an hour, Janós sister finally appeared but was severely weakened because of the great pain from torture and torment, so much so that she could barely hold out her hands and was bitterly crying and whining.[42] After this it was said that Janós' sister died and was buried in Beckov.[42] Martinus also claimed that he knew Bathory had killed the daughters of a nobleman named Georgius Tukynzky and another nobleman named Benedictus Barbel.[42] Martinus also claimed that he heard how Bathory had torn the flesh of virgins, grounded it into minced meat and allowed to be served before them.[42] This testimony was collected by András of Keresztúr and was published on July 28, 1611, on the orders of King Matthias II.[37]

Bathory is said to have tortured or killed peasants for years; their disappearances were not likely to provoke an investigation.[43] The abuse of lower classes by nobles was frowned upon but not actually prohibited by law.[43] However, she eventually began killing daughters of the lesser gentry, some of whom were sent to live with her hoping to learn from her and benefit from a connection to the high-ranking countess.[44]

Some witnesses named relatives who died while at the gynaeceum. Others reported having seen traces of torture on dead bodies, some of which were buried in graveyards, and others in unmarked locations.

Veracity of accusations

[edit]Beginning in the 1980s, scholars have questioned the truthfulness of the claims against Bathory.[43] Several authors, such as László Nagy and Irma Szádeczky-Kardoss, have argued that Elizabeth Báthory was a victim of a politically motivated frameup.[7][45] Nagy argued that the proceedings against Báthory were largely politically motivated, possibly due to her extensive wealth and ownership of large areas of land in Hungary, which increased after the death of her husband. At that time, Hungary was embroiled in religious and political conflicts, especially relating to the wars with the Ottoman Empire, the spread of Protestantism and the extension of Habsburg power and political centralization at the expense of the military and political power of Austria and Hungary's noble houses.[46] The Habsburgs were Catholic and Báthory was a Calvinist.[7] Her nephew, Prince Gábor Báthory, ruled in Transylvania, which was influential in the movement for Ottoman-backed Hungarian independence from Habsburg rule, providing the Imperial Court in Vienna a further motivation to discredit the Báthory family.[7] Prince Gábor also desired the throne of Hungary, presenting a threat to King Matthias.[7] Elizabeth Báthory's vast land holdings included fortresses that could have aided the Transylvanian army if Gábor had sent it to challenge Matthias.[7] Matthias, who had originally ordered the investigation into Báthory, owed her a large financial debt, which was cancelled after she was arrested.[2]

The legalities of the trial were complicated. King Matthias believed that if Erzsébet received the death penalty, her property would cede to the Crown and his debts would be cancelled.[47] By January 1611 he was angered that the death penalty was not being discussed against Bathory, based on the proceedings brought by his two notaries to gather testimonies, Mózes Cziráky and András of Keresztúr.[48] On January 14, 1611, King Matthias wrote a letter to Count Gyorgy Thurzo expressing his dissatisfaction with the movement of the case, and the need for justice to be brought to Bathory, and for Bathory to be interrogated at Castle Cjesthe.[49] The letter said: "We instruct you earnestly and we give you the emergency order as soon as your receive this letter, that you immediately summon this woman Erzsébet Bathory on the said date or through dates of letters to your bondsmen and by warrant of the honorable Chapter of the Metropolitan Church of Esztergom to appear at Castle Cjesthe with leave to discover and discuss her aforementioned immense and outrageous deeds and that the judgement proceed and be carried out in fulfillment of the law, whether she appears personally or sends someone or not, and warn at the front where you set the date and place she personally or by legal representation appear before you. Your handling of the matter, however, given the insistence of the parties involved, has to be done in accordance with the law. Anything else shall not proceed."[49] This letter explains how King Matthias and Thurzo were not on the same page, regarding how to proceed with Bathory after her arrest.

On the Contrary, Bathory's son-in-law Miklós Zrínyi had thanked Thurzo in a letter that he wrote to Thurzo, dated February 12, 1611, regarding how Thurzo was treating his mother-in-law post arrest.[50] An excerpt from this letter states: "I heard the news of the shameful and miserable situation of my wife's mother, Mrs. Nádasdy (Elizabeth Bathory) in view of her immense, shameful deeds, I must confess that, regarding a penalty, you have chosen the lesser of two evils. The judgement of your Grace served us for the better, because it has preserved our honor and shielded us from too great a shame. When, in your letters, you made known to us the will of His Royal Majesty (King Matthias), including punishment by horrible, judicial torture, we, her relatives, felt that we must all die of shame and disgrace."[50] This letter demonstrates that Thurzo didn't want to disgrace the Bathory name. And wanted to keep her crimes as far away from the public eye as possible.

The investigation into Báthory's crimes, however, was sparked by insistent complaints from a Lutheran minister, István Magyari[31] and Thurzó was also a Lutheran, which does not align with the notion of a Catholic/Habsburg plot against the Protestant Báthory family. However, religious tension was still a possible source of conflict, as the Báthorys were Calvinists rather than Lutherans.[25]

Thurzó, the investigator into the accusations, had political state ambitions that would benefit from disgracing Báthory.[7] An ally of King Matthias, he had been involved in an assassination attempt on Báthory's cousin Prince Gábor, and he had ambitions for his son to become Prince of Transylvania, in competition with Elizabeth Báthory's son.[7] Thurzó alleged that he found numerous dead and dying girls when he entered the castle,[10] but Szádeczky-Kardoss argues that the physical evidence was exaggerated and Thurzó misrepresented dead and wounded patients as victims of Báthory.[7] Landowners like Báthory were responsible for medical care of tenants, so sick and injured subjects were brought to her castles.[7] Female landowners were charged with care of female patients.[7]

Despite this, there were a handful of people who provided first hand accounts of Bathory's crimes at the trial. One of these people was Janós Deseö, who was warden (castellan) of Castle Keresztúr.[51] He testified that his niece, named Kata Berényi, had been accepted to work at the Countess' court, however it was alleged, thru rumors, that his niece was being mistreated by Bathory.[52] He wanted to see if these rumors were true, so after learning that his niece, Kata, would accompany Bathory on an extended trip to Castle Cjesthe, he planned to intercept the party to see his niece before they left. After Deseö intercepted the entourage, he asked Bathory "Might I please see my niece before you take your leave?" "I hear you are going to take her along to Cjesthe and no one knows when I am going to see her again, I also want to give her some money."[53] After spotting his niece, Kata, he realized that she was dejected, crying, and freezing cold and this brought Deseö to tears as well.[54] Deseö than said to Bathory: "Merciful Lady, please do not take my niece with you! I implore you in the name of God, not by me but by all my relatives". He continued: " We indeed see that she does not know how to serve the will of Your Grace."[55] At this point, Bathory then said: "I certainly will not give her back, because she has already escaped from me three times, All the more I will kill her."[56] After this incident, Deseö stated that: " Bathory indeed took her away and never brought her back, tormenting her so much that she died."[54]

Another witness was Lady Barbara Bixi, who was residing at Castle Keresztúr and was twenty five years old when she was sworn in and interrogated.[57] She stated that she was an attendant of the mistress, (Bathory), and had been travelling with her the last four months, (from which she was being interrogated).[57] She testified that Lady Bathory had tormented numerous girls at Bitcá, and that she had seen these girls with her own eyes. She added that Bathory had: "Beaten and thrashed them, cut their bodies, stabbed the unfortunates with needles, put stinging nettles into the girls wounds or covered them with nettles, as to torment them".[57] She testified that "she does not know the names of all the girls, because, in general, the girls were grabbed from anywhere and brought there."[57] Janos Ujvaly (Ficzko) corroborated this sentiment by stating that typically they would lure or outright kidnap girls from different places and bring them to the many different castles. Both Lady Barbara and Janos Deseo statements were collected by Mozes Cziraky and was published on December 14, 1611, on the orders of King Matthias II.[20] These confessions were not done under torture.

Arrest

[edit]On 13 December 1610, Nikola VI Zrinski confirmed the agreement with Thurzó about the imprisonment of Báthory and distribution of the estate.[32] On New Year's Eve 1610, Thurzó went to Csejte Castle and arrested Báthory along with four of her servants, who were accused of being her accomplices: Dorottya Szentés, Ilona Jó, Katarína Benická and János Újváry ("Ibis" or Ficzkó). According to Thurzó's letter to his wife, his unannounced visit found one dead girl and another living "prey" girl in the castle,[32] but there is no evidence that they asked her what had happened to her. She recovered but did not testify in the trials.[7] Although it is commonly believed that Báthory was caught in the act of torture, she was having dinner.[7] Initially, Thurzó made the declaration to Báthory's guests and villagers that he had caught her red-handed. However, she was arrested and detained prior to the discovery or presentation of the victims. It seems most likely that the claim of Thurzó's discovering Báthory covered in blood has been the embellishment of fictionalised accounts.[58]

Thurzó debated further proceedings with Báthory's son Paul and two of her sons-in-law, Nikola VI Zrinski and György Drugeth.[32] Her family, which ruled Transylvania, sought to avoid the loss of Báthory's property which was at risk of being seized by the crown following a public scandal.[citation needed] Thurzó, along with Paul and her two sons-in-law, originally planned for Báthory to be sent to a nunnery, but as accounts of her actions spread, they decided to keep her under strict house arrest.[59]

Two trials were held in the wake of Báthory's arrest: The first was held on 2 January 1611, and the second on 7 January 1611.[60] In the first trial, seventeen witnesses testified, including the four servants who were also fellow suspects. These suspects had been tortured before the proceedings.[7] They confessed, and stated that they were acting on Elizabeth's orders. After the trial, they were executed as her accomplices.[61] Ilona Jó and Dorottya Szentes had their fingers torn out with a pair of red-hot pincers and were then burned alive.[citation needed] Due to his youth and the belief that he was less culpable, János Újváry was executed by a much less painful method: beheading. Afterwards, his body was burned on the same pyre as Jó and Szentes.[citation needed] Another servant, Erzsi Majorova, initially escaped capture but was burned alive after being apprehended.[citation needed] Katarína Benická received a life sentence after evidence showed that she had been abused by the others.[citation needed]

The highest number of victims cited during the trial of Báthory's accomplices was 650, but this number comes from the claim by a servant named Susannah that Jakab Szilvássy, Báthory's court official, had seen the figure in one of Báthory's private books. The book was never revealed and Szilvássy never mentioned it in his testimony.[62]

It is very difficult to know with any certainty how many young woman Bathory is said to have killed. This is due to many compounding factors: firstly, her accomplices (Dorka, Ficzko, and Illona) all gave different numbers and were tortured into confessions.[63] Secondly, one should assume that not every dead body was found, like in most[citation needed] serial killer cases. Lastly, how many of the girls died directly at the hands of Bathory, as a result of her tortures, or had died of other reasons, is hard to prove. With this in mind, there are a couple of people who testified at the trial that could offer some insight. Benedek Bicsérdy was the castellan at Bathory's castle at Sarvar.[64] In October 1610, in the preliminary investigation of the Countess, he stated that he knew of at least 175 girls and women who had died at Castle Sarvar.[65] However, he added that he knew nothing regarding how they died because "unless Bathory had called for him, he was not permitted to go into the house of the Lady."[65] Another witness was named Baltazar Poby (also spelled Balthasar Poky); he was another castellan at Castle Sarvar.[66] He testified that he had heard the number of victims at Castle Sarvar, actually numbered over 200, "if not already mounting to nearly 300".[66]

These numbers only take into account the bodies found at one of Bathory's castles (in Sarvar). It doesn't include her other castles, including Castle Keresztúr and the infamous Castle Cjesthe.

Confinement and death

[edit]On 25 January 1611, Thurzó wrote a letter to King Matthias describing that they had captured and confined Báthory to her castle. The palatine also coordinated the steps of the investigation with the political struggle with the Prince of Transylvania.[clarification needed] She was detained in the castle of Csejte for the remainder of her life, where she died at the age of 54. György Thurzó wrote that Báthory was locked in a bricked room, but according to documents from the visit of priests in July 1614, she was able to move unhindered in the castle, more akin to house arrest.[67][68]

She wrote a will in September 1610, in which she left all current and future inheritance possessions to her children.[32] In the last month of 1610, she signed her arrangement, in which she distributed the estates, lands and possessions among her children.[69][9] On the evening of 20 August 1614, Báthory complained to her bodyguard that her hands were cold, whereupon he replied "It's nothing, mistress. Just go lie down". She went to sleep and was found dead the following morning.[70] She was buried in the church of Csejte on 25 November 1614,[70] but according to some sources due to the villagers' uproar over having the Countess buried in their cemetery, her body was moved to her birth-home at Ecsed, where it was intered at the Báthory family crypt.[71] The location of her body today is unknown but believed to be buried deep in the church area of the castle. The Csejte church and the castle of Csejte do not bear any markings of her possible grave.[citation needed]

The Gynaecaeum

[edit]In the Winter of 1609, Bathory had opened a Gynaecaeum, which is similar to a finishing school, and it was opened for high born young women.[72] The Gynaeceum brought in much needed funding and provided a new type of victim for Bathory to kill after many peasant families in the local villages surrounding her castle declined to let their daughters work at the castles after the reputation of Bathory had spread amongst the Kingdom.[72] On the contrary, many noble families were eager to send their daughters to her court, so their social status would increase and they could learn courtly etiquette.[72] However, once their daughters did not come back home, they eventually appealed to King Matthias for answers.

Noblewoman Anna Zelesthey who resided in the town of Milhalifalva, was 54 years old when she was sworn in and interrogated.[73] Anna testified that her own daughter named Zsuzska was accepted to attend Lady Bathory's court.[73] However, she testified that she can say with certainty and also from what others had told her, that her daughter was tortured, tormented, and beaten so badly that she was killed in the Gynaecaeum.[73] She also testified that it was Lady Bathory who beat, tortured, and tormented her daughter to death based on what she was told by others.[73] This testimony was collected by Mózes Cziráky and was published on December 14, 1611, on the orders of King Matthias.[74]

A Noblewoman named Anna Köszeghy, was 32 years old when she was sworn in and interrogated.[75] She testified that she would make numerous trips to Bathory's Gynaecaeum and saw many of the victims in a tortured state. She testified that their fingers were broken and hands were scorched.[75] She testified that when she asked these girls about their hands being burned, they told her that Bathory had burned them with red hot irons.[75] Another Noblewoman named Dorottya Jezernyczky was 45 years old when she was sworn in and interrogated.[76] She testified that she sent her own daughter named Erzsébet to this Gynaecaeum, and that she was killed in the Gynaecaeum.[76] These testimonies were published on July 28, 1611, by András of Keresztúr on the orders of King Matthias.[37]

The Castellan of Castle Cjesthe(Cachtice), was a man named Michael Horvath and he stated that he knew of at least seven girls who had died at the Gynaecaeum.[77] He stated that these seven bodies had been buried in a little garden behind the courtyard in Castle Cjesthe, but they had not been buried deep enough, so dogs had dug up the corpses and were carrying around body parts in their mouths.[77]

It was alleged that in a matter of weeks, that all of the attendants in her Gynaecaeum had been killed.[41] When Nobles began to press Bathory on why their daughters had gone missing, Bathory concocted this story that one of the girls in her Gynaecaeum had gone crazy and killed all of the other attendants and then killed herself.[41] She alleged that this girl did this because she was greedy for jewelry.[41]

During this time, dozens of complaints from the Hungarian nobles began to flood the King's and Palatine's courts, accusing Bathory of torturing and murdering noble girls.[41] This time the King couldn't ignore the complaints and sent his two notaries (Mózes Cziráky and András of Keresztúr) and György Thurzo to investigate the claims.

It was also said that during this time one of Bathory's victims actually managed to escape from Cjesthe and went into the nearby village and alerted the locals about the goings on at Cjesthe.[78] It was also said that this girl had a knife stuck in her foot.[78]

Folklore and popular culture

[edit]The case of Elizabeth Báthory inspired numerous stories during the 18th and 19th centuries. The most common motif of these works was that of the countess bathing in her virgin victims' blood to retain beauty or youth. This legend appeared in print for the first time in 1729, in the Jesuit scholar László Turóczi's Tragica Historia, the first written account of the Báthory case.[79] The story came into question in 1817 when the witness accounts (which had surfaced in 1765) were published for the first time. They included no references to blood baths.[80] In his book Hungary and Transylvania, published in 1850, John Paget describes the supposed origins of Báthory's blood-bathing, although his tale seems to be a fictionalised recitation of oral history from the area.[81] It is difficult to know how accurate his account of events is. Sadistic pleasure is considered a far more plausible motive for Báthory's crimes.[82]

Báthory has been disregarded by Guinness World Records as the most prolific female murderer, because the number of her victims is debated.[83]

See also

[edit]- Elizabeth Branch

- Elizabeth Brownrigg

- Kateřina of Komárov

- Delphine LaLaurie

- Catalina de los Ríos y Lisperguer

- Darya Nikolayevna Saltykova

- List of serial killers by country

References

[edit]- ^ Barker, Roland C. (2001). Bad People in History. New York: Gramercy Books. p. 7. ISBN 9780517163115.

- ^ a b Pallardy, Richard. "Elizabeth Bathory | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ a b Ramsland, Katherine. "Lady of Blood: Countess Bathory". Crime Library. Turner Entertainment Networks Inc. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "The Blood Countess: History's Most Prolific Female Serial Killer". Treehugger. Retrieved 6 November 2025.

- ^ a b HISTORY.com Editors (13 November 2009). "Hungarian countess's torturous escapades are exposed | December 29, 1610". HISTORY. Retrieved 6 November 2025.

- ^ McNally, Raymond T. (1983). Dracula Was a Woman: In Search of the Blood Countess of Transylvania. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-07-045671-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Szádeczky-Kardoss, Irma. "The Bloody Countess? An Examination of the Life and Trial of Erzsébet Báthory". Notes on Hungarian History (Based on the author's monograph). Translated by Nehrebeczky, Lujza. Hungarian original published in September 2, 2005 and September 9, 2005 issues of Élet és Tudomány.

- ^ Levack, Brian P. (28 March 2013). The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America. OUP Oxford. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-19-164883-0.

- ^ a b Lengyel, Tünde; Várkonyi, Gábor (2011). Báthory Erzsébet, egy asszony élete [Erzsébet Báthory: The Life of a Woman]. Budapest: General Press. pp. 285–291. ISBN 9789636431686.

- ^ a b Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of Horror: The Life and Work of Elisabeth Báthory: In Letters, Testimonies and Fantasy Games] (in German). p. 293. OCLC 654683776.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bartosiewicz, Aleksandra (December 2018). "Elisabeth Báthory – a true story". Przegląd Nauk Historycznych. 17 (3). Lodz University Press, Poland: 103–122. doi:10.18778/1644-857X.17.03.04. hdl:11089/27178. S2CID 188107395.

- ^ "The Plain Story". Elizabethbathory.net. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ McNally, Raymond T. (1983). Dracula Was a Woman: In Search of the Blood Countess of Transylvania. New York City: McGraw-Hill. pp. 11–13. ISBN 978-0-07-045671-6.

- ^ Joshi, S. T. (2011). Encyclopedia of the Vampire: The Living Dead in Myth, Legend, and Popular Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 6. ISBN 9780313378331. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ Stoker, Bram; Eighteen-Bisang, Robert; Miller, Elizabeth (2008). Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula: A Facsimile Edition. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 131. ISBN 9780786477302. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ "The Blood Countess: 10 Facts About Elizabeth Báthory". History Hit. Retrieved 6 November 2025.

- ^ a b c Craft 2009, p. 137.

- ^ Craft 2009, pp. 285–290.

- ^ Craft 2009, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Craft 2009, p. 283.

- ^ Craft 2009, p. 285.

- ^ Craft 2009, p. 286.

- ^ a b Craft 2009, pp. 287, 288.

- ^ a b Craft 2009, p. 288.

- ^ a b c Thorne, Tony (2012). Countess Dracula: The Life and Times of Elisabeth Bathory, the Blood Countess. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781408833650.

- ^ a b The most notorious serial killers : ruthless, twisted murderers whose crimes chilled the nation. United Kingdom: TI Incorporated Books. 2017. ISBN 9781683300274. OCLC 982117998.

- ^ a b c d Leslie, Carroll (2014). Royal Pains: A Rogues' Gallery of Brats, Brutes, and Bad Seeds. New York City: New American Library. pp. 160–161. ISBN 9781101478776. OCLC 883306686.

- ^ Holmes, Gregory L. (January 1995). "The falling sickness. A history of epilepsy from the Greeks to the beginnings of modern neurology". Journal of Epilepsy. 8 (1). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier: 214–215. doi:10.1016/s0896-6974(95)90017-9. ISSN 0896-6974. PMC 1081463.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (1999). The Vampire Book. p. 42. ISBN 1-57859-076-0.

- ^ "História hradu". Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ a b Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). pp. 234–237. OCLC 654683776.

- ^ a b c d e f Kord, Susanne (2009). Murderesses in German Writing, 1720–1860: Heroines of Horror. Cambridge University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-521-51977-9.

- ^ Letters from Thurzó to both men on 5 March 1610, printed in Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). pp. 265–266, 276–278. OCLC 654683776.

- ^ a b Craft 2014, p. 356.

- ^ a b c Craft 2014, p. 357.

- ^ Craft 2014, p. 360.

- ^ a b c Craft 2014, p. 364.

- ^ a b Craft 2014, p. 235.

- ^ "Elizabeth Bathory - Death, Children & Facts". Biography. 3 October 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2025.

- ^ "The Blood Countess: 10 Facts About Elizabeth Báthory". History Hit. Retrieved 22 November 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Craft 2014, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d e f Craft 2014, p. 353.

- ^ a b c O'Connell, Ronan (21 October 2022). "The bloody legend of Hungary's serial killer countess". National Geographic. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ McNally, Raymond T. (1983). Dracula Was a Woman: In Search of the Blood Countess of Transylvania. New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 44, 48–49. ISBN 978-0-07-045671-6.

- ^ Nagy, László. A rossz hirü Báthoryak. Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó 1984[page needed]

- ^ Szakály, Ferenc (1994). "The Early Ottoman Period, Including Royal Hungary, 1526–1606". In Sugar, Peter F. (ed.). A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. pp. 83–99. ISBN 978-0-253-20867-5.

- ^ Craft 2009, p. 171.

- ^ Craft 2009, pp. 171, 202, 212.

- ^ a b Craft 2009, p. 172.

- ^ a b Craft 2009, p. 174.

- ^ Craft 2009, pp. 109, 110, 291, 292.

- ^ Craft 2009, pp. 108, 109.

- ^ Craft 2009, p. 109.

- ^ a b Craft 2009, p. 292.

- ^ Craft 2009, pp. 109, 292.

- ^ Craft 2009, pp. 110, 292.

- ^ a b c d Craft 2009, p. 293.

- ^ Thorne, Tony (1997). Countess Dracula. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9780747536413.

- ^ A letter from 12 December 1610 by Elizabeth's son-in-law Zrínyi to Thurzó refers to an agreement made earlier. See Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). p. 291. OCLC 654683776.

- ^ "No Blood in the Water: The Legal and GenderConspiracies Against Countess Elizabeth Bathory in Historical Context". Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ McNally, Raymond T. (1983). Dracula Was a Woman: In Search of the Blood Countess of Transylvania. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-07-045671-6.

- ^ Thorne, Tony (1997). Countess Dracula. London, England: Bloomsbury. p. 53. ISBN 978-1408833650.

- ^ "Elizabeth Bathory - Death, Children & Facts". Biography. 3 October 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2025.

- ^ Craft 2009, p. 57.

- ^ a b Craft 2014, p. 82.

- ^ a b Craft 2014, p. 83.

- ^ Bledsaw, Rachael (20 February 2014). No Blood in the Water: The Legal and Gender Conspiracies Against Countess Elizabeth Bathory in Historical Context (MS thesis). Illinois State University. doi:10.30707/ETD2014.Bledsaw.R.

- ^ Ferencné, Palkó (2014). Báthory Erzsébet Pere (BA thesis). University of Miskolc.

- ^ Szádeczky-Kardoss Irma – Báthory Erzsébet igazsága / The truth of Elizabeth Báthory (10 years of research using contemporary correspondence)

- ^ a b Craft 2009, p. 298.

- ^ Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). p. 246. OCLC 654683776.

- ^ a b c Craft 2014, p. 185.

- ^ a b c d Craft 2014, p. 366.

- ^ Craft 2014, p. 374.

- ^ a b c Craft 2014, p. 358.

- ^ a b Craft 2014, p. 359.

- ^ a b Craft 2014, p. 186.

- ^ a b Craft 2014, p. 188.

- ^ in Ungaria suis *** regibus compendia data, Typis Academicis Soc. Jesu per Fridericum Gall. Anno MCCCXXIX. Mense Sepembri Die 8. p 188–193, quoted by Farin

- ^ Hesperus, Prague, June 1817, Vol. 1, No. 31, pp. 241–248 and July 1817, Vol. 2, No. 34, pp. 270–272

- ^ Paget, John (1850). Hungary and Transylvania; with remarks on their condition, Social, Political and Economical. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard. pp. 50–51.

- ^ Alois Freyherr von Mednyansky: Elisabeth Báthory, in Hesperus, Prague, October 1812, vol. 2, No. 59, pp. 470–472, quoted by Farin, Michael (1989). Heroine des Grauens: Wirken und Leben der Elisabeth Báthory: in Briefen, Zeugenaussagen und Phantasiespielen [Heroine of horror: the life and work of Elisabeth Báthory: in letters, testimonies and fantasy games] (in German). pp. 61–65. OCLC 654683776.

- ^ "Most prolific female murderer". Guinness World Records. Guinness World Records Limited. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- McNally, Raymond T. (1983). Dracula Was a Woman: In Search of the Blood Countess of Transylvania. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-045671-6. Raymond T. McNally (1931–2002) was a professor of Russian and East European History at Boston College

- Thorne, Tony (1997). Countess Dracula. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-7475-2900-2.

- Penrose, Valentine (2006). The Bloody Countess: Atrocities of Erzsébet Báthory. translator: Trocchi, Alexander. Solar Books. ISBN 978-0-9714578-2-9. Translation from the French Erzsébet Báthory la Comtesse sanglante

- Craft, Kimberly (2009). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory. Kimberly L. Craft. ISBN 978-1-4495-1344-3.

- Craft, Kimberly L. (10 October 2014). Infamous Lady: The True Story of Countess Erzsébet Báthory (2nd ed.). Amazon. ISBN 978-1502581464.

- Ramsland, Katherine. "Lady of Blood: Countess Bathory". Crime Library. Turner Entertainment Networks Inc. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014.

- Zsuffa, Joseph (2015). Countess of the Moon. Griffin Press. ISBN 978-0-9828813-8-5.

External links

[edit]- The Blood Countess? – Epitome of Szádeczky-Kardoss Irma's research

- Elizabeth Bathory – the Blood Countess BBC piece on Erzsébet Báthory, Created 2 August 2001; Updated 28 January 2002

- "Elizabeth Báthory Drop of Blood Festival: 16 August 2014" (in Slovak). Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Festival in Čachtice, Slovakia

- A complete genealogy of all descendants Elizabeth Báthory (17th–20th century) Archived 26 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Novotny, Pavel (2014). Die Gräfin Elisabeth Bathory und das Geheimnis hinter dem Geheimnis [400 Years of Bloody Countess – The Secret Behind the Secret] (Motion picture). Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2014. (Documentary film)

- Elizabeth Báthory

- 1560 births

- 1614 deaths

- 16th-century criminals

- 16th-century Hungarian nobility

- 16th-century Hungarian women

- 16th-century landowners

- 16th-century women landowners

- 17th-century murderers

- 17th-century Hungarian people

- 17th-century Hungarian women

- 17th-century landowners

- 17th-century women landowners

- Báthory family

- Deal with the Devil

- Crimes involving Satanism or the occult

- Hungarian female serial killers

- Hungarian serial killers

- Hungarian people who died in prison custody

- People from Nyírbátor

- Royalty and nobility with epilepsy

- Serial killers who died in prison custody

- Torturers

- Vampirism (crime)

- Violence against women in Europe

- Dracula