Decolonisation of Africa

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: The article was recently merged with another large article, African independence movements. (October 2025) |

| This article duplicates the scope of other articles. |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

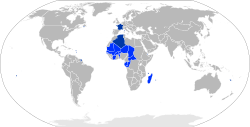

The decolonisation of Africa was a series of political developments in Africa that spanned from the mid-1950s to 1975, during the Cold War. Colonial governments gave way to sovereign states in a process often marred by violence, political turmoil, widespread unrest, and organised revolts. Major events in the decolonisation of Africa included the Mau Mau rebellion, the Algerian War, the Congo Crisis, the Angolan War of Independence, the Zanzibar Revolution, and the events leading to the Nigerian Civil War.[1][2][3][4][5]

| Part of a series on |

| Colonialism |

|---|

|

| Colonization |

| Decolonization |

Background

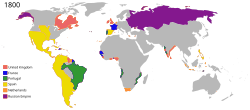

The Scramble for Africa between 1870 and 1914 was a significant period of European imperialism in Africa that ended with almost all of Africa, and its natural resources, claimed as colonies by European powers, who raced to secure as much land as possible while avoiding conflict amongst themselves. The partition of Africa was confirmed at the Berlin Conference of 1885, without regard for the existing political and social structures.[6][7]

Almost all the precolonial states of Africa lost their sovereignty. The only exceptions were Liberia, which had been settled in the early 19th century by formerly enslaved African-Americans and was recognized as independent by the United States in 1862[8] but was viewed by European powers as being in the United States' sphere of influence, and Ethiopia, which won its independence at the Battle of Adwa[9] but was later occupied by Italy in 1936.[10] Britain and France had the largest holdings, but Germany, Spain, Italy, Belgium, and Portugal also had colonies.[11]

By 1977, 50 African countries had gained independence from European colonial powers.[12][better source needed]

External causes

In the early 20th century, nationalism gained ground globally. Following the end of World War I, German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires according to the principles espoused in Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points. Though many anti-colonial intellectuals saw the potential of Wilsonianism to advance their aims, Wilson had no intention of applying the principle of self-determination outside the lands of the defeated Central Powers. The independence demands of Egyptian and Tunisian leaders, which would have compromised the interests of the victorious Allies, were not entertained. Though Wilsonian ideals did not endure as the interwar order broke down, the principle of an international order based on the self-determination of peoples remained relevant.

After 1919, anti-colonial leaders increasingly oriented themselves toward the Soviet Union's proletarian internationalism.[13]

Many Africans fought in both World War I and World War II. In World War I, African labor was essential on the Western Front, and African soldiers fought in the Sinai and Palestine campaign. Many Africans were not allowed to bear arms or serve on an equal basis with whites. The sinking of the SS Mendi in 1917 was a particularly tragic incident for Africans in the war, with 607 of the 646 crew killed being Black South Africans.[14] In the Second World War, Africans fought in both the European and Asian theatres of war.[15]

Approximately one million sub-Saharan Africans served in European armies in some capacity. Many Africans were compelled or even forced into military service by their respective colonial regimes, but some voluntarily enlisted in search of better opportunities than they could find in civilian employment.[16] This led to a deeper political awareness and the expectation of greater respect and self-determination, which went largely unfulfilled.[17] Because the victorious allied powers had no intention of withdrawing from their colonial holdings at the end of the war, and would instead need to rely on the resources and manpower of their African colonies during postwar reconstruction in Europe, the colonial powers downplayed Africans' contributions to the allied victory.[16]

On 12 February 1941, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met to discuss the post-World War II world. The result was the Atlantic Charter.[18] It was not a treaty and was not submitted to the British Parliament or the Senate of the United States for ratification, but it turned out to be a widely acclaimed document.[19] Clause Three referred to the right to decide what form of government people wanted, and to the restoration of self-government.

Prime Minister Churchill argued in the British Parliament that the document referred to "the States and nations of Europe now under the Nazi yoke".[20] President Roosevelt regarded it as applicable across the world.[21] Anticolonial politicians immediately saw it as relevant to colonial empires.[22]

In 1948, three years after the end of World War II, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognised all people as being born free and equal.[23]

Italy, a colonial power, lost its African empire, Italian East Africa, Italian Ethiopia, Italian Eritrea, Italian Somalia and Italian Libya, as a result of World War II.[24] Furthermore, colonies such as Nigeria, Senegal and Ghana pushed for self-governance as colonial powers were exhausted by war efforts.[25]

The United Nations 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples stated that colonial exploitation is a denial of human rights, and that power should be transferred back to the countries or territories concerned.[26]

Internal causes

Colonial economic exploitation involved diverting resource extraction, such as mining, profits to European shareholders at the expense of internal development, causing significant local socioeconomic grievances.[27] For early African nationalists, decolonisation was a moral imperative around which a political movement could be assembled.[28][29]

In the 1930s, colonial powers cultivated, sometimes inadvertently, a small elite of local African leaders educated in Western universities, where they became familiar with ideas such as self-determination. Although independence was not encouraged, arrangements between these leaders and the colonial powers developed,[11] and such figures as Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya), Kwame Nkrumah (Gold Coast, now Ghana), Julius Nyerere (Tanganyika, now Tanzania), Léopold Sédar Senghor (Senegal), Nnamdi Azikiwe (Nigeria), Patrice Lumumba (DRC), António Agostinho Neto (Portuguese West Africa) now (Angola) and Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Côte d'Ivoire) came to lead the struggles for African nationalism.

During World War II, some local African industries and towns expanded when U-boats patrolling the Atlantic Ocean impeded the shipping of raw materials to Europe.[12][better source needed]

Over time, urban communities, industries, and trade unions grew, improving literacy and education, and leading to the establishment of pro-independence newspapers.[12][better source needed]

By 1945, the Fifth Pan-African Congress demanded the end of colonialism, and delegates included future presidents of Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, and other nationalist activists.[30]

Transition to independence

Following World War II, rapid decolonisation swept across the continent of Africa as many territories gained their independence from European colonisation.

In August 1941, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met to discuss their post-war goals. In that meeting, they agreed to the Atlantic Charter, which in part stipulated that they would, "respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them."[31] This agreement became the post-WWII stepping stone toward independence as nationalism grew throughout Africa.

Consumed by post-war debt, European powers could no longer afford to maintain control of their African colonies.[citation needed] This allowed African nationalists to negotiate decolonisation very quickly and with minimal casualties.[citation needed] Some territories, however, saw large death tolls as a result of their fight for independence.[citation needed]

Historian James Meriweather argues that American policy towards Africa was characterized by a middle road approach, which supported African independence but also reassured European colonial powers that their holdings would remain intact. Washington wanted the right type of African groups to lead newly independent states, in other words not communist and not especially democratic. Meriweather argues that nongovernmental organizations influenced American policy towards Africa. They pressured state governments and private institutions to disinvest from African nations not ruled by the majority population. These efforts also helped change American policy towards South Africa, as seen with the passage of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.[32]

British Empire

Ghana

On 6 March 1957, Ghana (formerly the Gold Coast) became the first sub-Saharan African country to gain its independence from European colonisation.[40] Starting with the 1945 Pan-African Congress, the Gold Coast's (modern-day Ghana's) independence leader Kwame Nkrumah made his focus clear. In the conference's declaration, he wrote, "We believe in the rights of all peoples to govern themselves. We affirm the right of all colonial peoples to control their own destiny. All colonies must be free from foreign imperialist control, whether political or economic."[41]

In 1948, three Ghanaian veterans were killed by the colonial police on a protest march. Riots broke out in Accra and though Nkrumah and other Ghanaian leaders were temporarily imprisoned, the event became a catalyst for the independence movement. After being released from prison, Nkrumah founded the Convention People's Party (CPP), which launched a wide-scale campaign in support of independence with the slogan "Self Government Now!"[42] Heightened nationalism within the country grew their power and the political party widely expanded.

In February 1951, the CPP gained political power by winning 34 of 38 elected seats, including one for Nkrumah who was imprisoned at the time. The British government revised the Gold Coast Constitution to give Ghanaians a majority in the legislature in 1951. In 1956, Ghana requested independence inside the Commonwealth, which was granted peacefully in 1957 with Nkrumah as prime minister and Queen Elizabeth II as sovereign.[43]

Winds of Change

Prime Minister Harold Macmillan gave the famous "Wind of Change" speech in South Africa, in February 1960, where he spoke to the country's Parliament of "the wind of change blowing through this continent."[44] Macmillan urgently wanted to avoid the same kind of colonial war that France was fighting in Algeria. Under his premiership, decolonisation proceeded rapidly.[45]

Britain's remaining colonies in Africa, except for Southern Rhodesia, were all granted independence by 1968. British withdrawal from the southern and eastern parts of Africa was not a peaceful process. Kenyan independence was preceded by the eight-year Mau Mau Uprising. In Rhodesia, the 1965 Unilateral Declaration of Independence by the white minority resulted in a civil war that lasted until the Lancaster House Agreement of 1979, which set the terms for recognised independence in 1980, as the new nation of Zimbabwe.[46]

Britain has moved to return its last British-occupied possession in Africa by signing a formal agreement in 2025 transferring sovereignty over the Chagos Islands to Mauritius. Under the terms of the agreement, the strategic atoll of Diego Garcia and its 38-kilometre buffer zone are immediately returned to Mauritius. This agreement allows for the continued operation of the joint Anglo-American base on Diego Garcia.[47]

Belgium

Belgium controlled several territories and concessions during the colonial era, principally the Belgian Congo (modern DRC) from 1908 to 1960 and Ruanda-Urundi (modern Rwanda and Burundi) from 1922 to 1962. It also had a small concession in China (1902–1931) and was a co-administrator of the Tangier International Zone in Morocco.

Roughly 98% of Belgium's overseas territory was just one colony, about 76 times larger than Belgium itself, known as the Belgian Congo. The colony was founded in 1908 following the transfer of sovereignty from the Congo Free State, which was the personal property of Belgium's king, Leopold II. The violence used by Free State officials against indigenous Congolese and the ruthless system of economic extraction had led to intense diplomatic pressure on Belgium to take official control of the country. Belgian rule in the Congo was based on the "colonial trinity" (trinité coloniale) of state, missionary and private company interests. During the 1940s and 1950s, the Congo experienced extensive urbanization and the administration aimed to make it into a "model colony". As the result of a widespread and increasingly radical pro-independence movement, the Congo achieved independence, as the Republic of Congo-Léopoldville in 1960.

Of Belgium's other colonies, the most significant was Ruanda-Urundi, a portion of German East Africa, which was given to Belgium as a League of Nations Mandate, when Germany lost all of its colonies at the end of World War I. Following the Rwandan Revolution, the mandate became the independent states of Burundi and Rwanda in 1962.[48]

French colonial empire

The French colonial empire began to fall during World War II when the Vichy France regime controlled the Empire. One after another, most of the colonies were occupied by foreign powers with Japan in Indochina, Britain in Syria, Lebanon, and Madagascar, the United States and Britain in Morocco and Algeria, and Germany and Italy in Tunisia. Control was gradually reestablished by Charles de Gaulle, who used the colonial bases as a launching point to help expel the Vichy government from Metropolitan France. De Gaulle, together with most Frenchmen, was committed to preserving the Empire in its new form. The French Union, included in the Constitution of 1946, nominally replaced the former colonial empire, but officials in Paris remained in full control. The colonies were given local assemblies with only limited local power and budgets. A group of elites, known as evolués, who were natives of the overseas territories but lived in metropolitan France emerged.[50][51][52]

De Gaulle assembled a major conference of Free France colonies in Brazzaville, in central Africa, in January–February 1944. The survival of France depended on support from these colonies, and De Gaulle made numerous concessions. These included the end of forced labour, the end of special legal restrictions that applied to natives but not to whites, the establishment of elected territorial assemblies, representation in Paris in a new "French Federation", and the eventual representation of Sub-Saharan Africans in the French Assembly. However, Independence was explicitly rejected as a future possibility:

- The ends of the civilizing work accomplished by France in the colonies excludes any idea of autonomy, all possibility of evolution outside the French bloc of the Empire; the eventual Constitution, even in the future of self-government in the colonies is denied.[53]

Conflicts

After World War II ended, France was immediately confronted with the beginnings of the decolonisation movement. In Algeria demonstrations in May 1945 were repressed with an estimated 20,000-45,000 Algerians killed.[54] Unrest in Haiphong, Indochina, in November 1945 was met by a warship bombarding the city.[55] Paul Ramadier's (SFIO) cabinet repressed the Malagasy Uprising in Madagascar in 1947. French officials estimated the number of Malagasy killed from as low as 11,000 to a French Army estimate of 89,000.[56]

In Cameroon, the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon's insurrection which began in 1955 headed by Ruben Um Nyobé, was violently repressed over two years, with perhaps as many as 100,000 people killed.[57]

Algeria

French involvement in Algeria stretched back a century. Ferhat Abbas and Messali Hadj's movements marked the period between the two wars, but both sides radicalised after the Second World War. In 1945, the Sétif massacre was carried out by the French army. The Algerian War started in 1954. Atrocities characterized both sides, and the number killed became highly controversial estimates that were made for propaganda purposes.[58] Algeria was a three-way conflict due to the large number of "pieds-noirs" (Europeans who had settled there in the 125 years of French rule). The political crisis in France caused the collapse of the Fourth Republic, as Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958 and finally pulled the French soldiers and settlers out of Algeria by 1962.[59][60] Lasting more than eight years, the estimated death toll typically falls between 300,000 and 400,000 people.[61] By 1962, the National Liberation Front was able to negotiate a peace accord with de Gaulle, the Évian Accords[62] in which Europeans would be able to return to their native countries, remain in Algeria as foreigners or take Algerian citizenship. Most of the one million Europeans in Algeria poured out of the country.[63]

French Community

French conservatives were disillusioned with the colonial experience after the disasters in Indochina and Algeria. They wanted to cut all ties to the numerous colonies in French Sub-Saharan Africa. During the war, de Gaulle had successfully based his Free France movement and the African colonies. After a visit in 1958, he made a commitment to make sub-Saharan French Africa a major component of his foreign-policy.[64] The French Union was replaced in the new Constitution of 1958 by the French Community. Only Guinea refused by referendum to take part in the new colonial organisation. However, the French Community dissolved itself amid the Algerian War; almost all of the other African colonies were granted independence in 1960, following local referendums. Some colonies chose instead to remain part of France, under the status of overseas départements (territories). Critics of neocolonialism claimed that the Françafrique had replaced formal direct rule. They argued that while de Gaulle was granting independence, on one hand, he was creating new ties with the help of Jacques Foccart, his counsellor for African matters. Foccart supported in particular the Nigerian Civil War during the late 1960s.[65]

Robert Aldrich argues that with Algerian independence in 1962, it appeared that the Empire practically had come to an end, as the remaining colonies were quite small and lacked active nationalist movements. However, there was trouble in French Somaliland (Djibouti), which became independent in 1977. There also were complications and delays in the New Hebrides Vanuatu, which was the last to gain independence in 1980. New Caledonia remains a special case under French suzerainty.[66] The Indian Ocean island of Mayotte voted in a referendum in 1974 to retain its link with France and forgo independence.[67]

Portugal

Unlike other European nations during the 1950s and 1960s, the Portuguese Estado Novo regime did not withdraw from its African colonies. During the 1960s, various armed independence movements became active in Portuguese Africa. The Portuguese Colonial War, also known as the Angolan, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambican War of Independence, was a 13-year-long conflict fought between Portugal's military and the emerging nationalist movements in Portugal's African colonies between 1961 and 1974. The Portuguese regime at the time, the Estado Novo, was overthrown by a military coup in 1974, and the change in government brought the conflict to an end.[68] From May 1974 to the end of the 1970s, over 500,000 Portuguese citizens from Portugal's African territories (mostly from Portuguese Angola and Mozambique) left those territories as refugees—the retornados.[69][70]

United States

Colony of Liberia

The Colony of Liberia, later the Commonwealth of Liberia, was a private colony of the American Colonization Society (ACS) beginning in 1822. It became an independent nation—the Republic of Liberia—after declaring independence in 1847.

| Country | Colonial name | Colonial power | Independence date | First head of state | Independence won through |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 July 1847[az] | Joseph Jenkins Roberts[ba] William Tubman |

Liberian Declaration of Independence |

Acquisition of sovereignty

| Country | Date of acquisition of sovereignty | Acquisition of sovereignty |

|---|---|---|

| 3 July 1962 | French recognition of Algerian referendum on independence held two days earlier | |

| 11 November 1975 | Independence from Portugal | |

| 1 August 1960 | Independence from France | |

| 30 September 1966 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 5 August 1960 | Independence from France | |

| 1 July 1962 | Independence from Belgium | |

| 24 September 1973 10 September 1974 (recognised) 5 July 1975[bb] |

Independence from Portugal | |

| 1 January 1960 | Independence from France | |

| 13 August 1960 | Independence from France | |

| 11 August 1960 | Independence from France | |

| 6 July 1975 | Independence from France declared | |

| 30 June 1960 | Independence from Belgium | |

| 15 August 1960 | Independence from France | |

| 27 June 1977 | Independence from France | |

| 28 February 1922 | The UK ends its protectorate, granting independence to Egypt | |

| 12 October 1968 | Independence from Spain | |

| 1 June 1936 5 May 1941 19 May 1941 10 February 1947 19 February 1951 15 September 1952 |

Abyssinian campaign, independence from Ethiopia declared | |

| 6 September 1968 | Independence from the United Kingdom under the name Swaziland | |

| 900 BC | D'mt Kingdom | |

| 17 August 1960 | Independence from France | |

| 18 February 1965 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 6 March 1957 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 2 October 1958 | Independence from France | |

| 24 September 1973 10 September 1974 (recognised) 5 July 1975[bc] |

Independence from Portugal declared | |

| 4 December 1958 | Autonomous republic within French Community | |

| 7 August 1960 | Independence from France | |

| 12 December 1963 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 4 October 1966 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 26 July 1847 | Independence from American Colonization Society | |

| 24 December 1951 | Independence from UN Trusteeship (British and French administration after Italian governance ends in 1947) | |

| 14 October 1958 | The Malagasy Republic was created as autonomous state within French Community | |

| 26 June 1960 | France recognizes Madagascar's independence | |

| 6 July 1964 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 25 November 1958 | French Sudan gains autonomy | |

| 24 November 1958 4 April 1959 20 June 1960 20 August 1960 22 September 1960 |

Independence from France | |

| 28 November 1960 | Independence from France | |

| 12 March 1968 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 7 April 1956 | Independence from France and Spain | |

| 25 June 1975 | Independence from Portugal | |

| 21 March 1990 | Independence from South African rule | |

| 4 December 1958 | Autonomy within French Community | |

| 23 July 1900 13 October 1922 13 October 1946 26 July 1958 20 May 1957 25 February 1959 25 August 1958 3 August 1960 8 November 1960 10 November 1960 |

Independence from France | |

| 1 October 1960 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 1 July 1962 | Independence from Belgium | |

| 12 July 1975 | Independence from Portugal | |

| 25 November 1957 24 November 1958 4 April 1959 4 April 1960 20 August 1960 20 June 1960 22 September 1960 18 February 1965 30 September 1989 |

Independence from France | |

| 29 June 1976 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 27 April 1961 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 20 July 1887 26 May 1925 1 June 1936 3 August 1940 19 August 1940 8 April 1941 25 February 1941 10 February 1947 1 April 1950 26 June 1960 1 July 1960 |

Union of Trust Territory of Somalia (former Italian Somaliland) and State of Somaliland (formerly British Somaliland) | |

| 11 December 1931 | Statute of Westminster, which establishes a status of legislative equality between the self-governing dominion of the Union of South Africa and the UK | |

| 31 May 1910 | Creation of the autonomous Union of South Africa from the previously separate colonies of the Cape, Natal, Transvaal and Orange River | |

| 9 July 2011 | Independence from Sudan after a civil war. | |

| 1 January 1956 | Independence from Egyptian and British joint rule | |

| 9 December 1961 | Independence of Tanganyika from the United Kingdom | |

| 30 August 1958 | Autonomy within French Union | |

| 27 April 1960 | Independence from France | |

| 20 March 1956 | Independence from France | |

| 1 March 1962 | Self-government granted | |

| 9 October 1962 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 24 October 1964 | Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 11 November 1965 | Unilateral declaration of independence by Southern Rhodesia | |

| 18 April 1980 | Recognized independence from the United Kingdom as Zimbabwe |

Modern colonialism

Colonialism in the colonial era, mostly refers to Western European countries' colonisation of lands in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania. The main European countries active in this form of colonization included Spain, Portugal, France, the Tsardom of Russia (later Russian Empire and Soviet Union), the Kingdom of England (later Great Britain), the Netherlands, Belgium[71] and the Kingdom of Prussia (now mostly Germany), and, beginning in the 18th century, the United States. Most of these countries had a period of almost complete dominance of world trade at some stage in the period from roughly 1500 to 1900. Beginning in the late 19th century, Imperial Japan also engaged in settler colonization, most notably in Hokkaido and Korea.

While some European colonisation focused on shorter-term exploitation of economic opportunities (Newfoundland, for example, or Siberia) or addressed specific goals such as settlers seeking religious freedom (Massachusetts), at other times long-term social and economic planning was involved for both parties, but more on the colonizing countries themselves, based on elaborate theory-building (note James Oglethorpe's Colony of Georgia in the 1730s and Edward Gibbon Wakefield's New Zealand Company in the 1840s).[72] In some cases European colonization appeared to be primarily for long-term economic gain, as in the Congo where Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness described life under the rule of King Leopold II of Belgium in the 19th century and Siddharth Kara has described colonial rule and European and Chinese influence in the 20th and 21st centuries.[71]

Colonisation may be used as a method of absorbing and assimilating foreign people into the culture of the imperial country. One instrument to this end is linguistic imperialism, or the use of non-indigenous colonial languages to the exclusion of any indigenous languages from administrative (and often, any public) use.[73]

Many African independence movements took place in the 20th century, when a wave of struggles for independence in European-ruled African territories were witnessed. World War II (1939-1945) served as the catalyst for many of these movements, as it devastated both the colonial empires and their African territories. The colonial powers were distracted by the war against Nazi Germany, and thus had less time and resources devoted to their colonies, weakening their influence.[74]

After WW2, Harry Truman and Winston Churchill introduced the Atlantic Charter, which declared that the United States and Britain would "respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live." The United Nations was also formed, and colonial powers were required to make annual reports on their territories, and it gave Africans a voice to list their grievances. The end of WW2 also saw the decline of Britain and France, and the rise of the United States and the USSR, which did not support colonial Europe's overseas territories.[74]

Notable independence movements took place:

- Algeria (former French Algeria), see Algerian War

- Angola (former Portuguese Angola), see Portuguese Colonial War

- Guinea-Bissau (former Portuguese Guinea), see Portuguese Colonial War

- Madagascar (former French Madagascar), see Malagasy Uprising

- Mozambique (former Portuguese Mozambique), see Portuguese Colonial War

- Namibia (former South West Africa) against South Africa, see South African Border War

French Algeria

Colonization of Algeria

French colonization of Algeria began on June 14, 1830, when French soldiers arrived in a coastal town, Sidi Ferruch.[75] The troops did not encounter significant resistance, and within 3 weeks, the occupation was officially declared on July 5, 1830.[75] After a year of occupation over 3,000 Europeans (mostly French) had arrived ready to start businesses and claim land.[75] In reaction to the French occupation, Amir Abd Al-Qadir was elected leader of the resistance movement. On November 27, 1832, Abd Al-Qadir declared that he reluctantly accepted the position, but saw serving in the position as a necessity in order to protect the country from the enemy (the French).[75] Abd Al-Qadir declared the war against the French as jihad, opposed to liberation.[75] Abd Al-Qadir's movement was unique from other independence movements because the main call to action was for Islam rather than nationalism.[75] Abd Al-Qadir fought the French for nearly two decades, but was defeated when the Tijaniyya Brotherhood agreed to submit to French rule as long as "they were allowed to exercise freely the rites of their religion, and the honor of their wives and daughters was respected".[75] In 1847 Abd Al-Qadir was defeated and there were other resistance movements but none of them were as large nor as effective in comparison.[75] Due to the lack of effective large-scale organizing, Algerian Muslims "resorted to passive resistance or resignation, waiting for new opportunities," which came about from international political changes due to World War I.[75]

As World War I began, officials discussed drafting young Algerians into the army to fight for the French, but there was some opposition.[75] European settlers were worried that if Algerians served in the army, then those same Algerians would want rewards for their service and claim political rights (Alghailani). Despite the opposition, the French government drafted young Algerians into the French army for World War I.[75] Since many Algerians had fought as French soldiers during World War I, just as the European settlers had suspected, Muslim Algerians wanted political rights after serving in the war. Muslim Algerians felt it was all the more unfair that their votes were not equal to the other Algerians (the settler population) especially after 1947 when the Algerian Assembly was created. This assembly was composed of 120 members. Muslim Algerians who represented about 9 million people could designate 50% of the Assembly members while 900,000 non-Muslim Algerians could designate the other half.

Religion in Algeria

When the French arrived in Algeria in 1830, they quickly took control of all Muslim establishments.[75] The French took the land in order to transfer wealth and power to the new French settlers.[75] In addition to taking property relating Muslim establishments, the French also took individuals' property and by 1851, they had taken over 350,000 hectares of Algerian land.[75] For many Algerians, Islam was the only way to escape the control of French Imperialism.[75] In the 1920s and 30s, there was an Islamic revival led by the ulama, and this movement became the basis for opposition to French rule in Algeria.[75] Ultimately, French colonial policy failed because the ulama, especially Ibn Badis, utilized the Islamic institutions to spread their ideas of revolution.[75] For example, Ibn Badis used the "networks of schools, mosques, cultural clubs, and other institutions," to educate others, which ultimately made the revolution possible.[75] Education became an even more effective tool for spreading their revolutionary ideals when Muslims became resistant to sending their children to French schools, especially their daughters.[75] Ultimately, this led to conflict between the French and the Muslims because there were effectively two different societies within one country.[75]

Leading up to the fight for independence

The fight for independence, or the Algerian war, began with a massacre that occurred on May 8, 1945 in Setif, Algeria. After WWII ended, nationalists in Algeria, in alignment with the American anti-colonial sentiment, organized marches, but these marches became bloody massacres.[76] An estimated 6,000–45,000 Algerians were killed by the French army.[76] This event triggered a radicalization of Algerian nationalists and it was a crucial event in leading up to the Algerian War.

In response to the massacre, Messali Hadj, the leader of the independence party, the Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties (MTLD), "turned to electoral politics.[76] With Hadj's leadership, the party won multiple municipal offices.[76] But, in the 1948 elections the candidates were arrested by Interior Minister Jules Moch.[76] While the candidates were being arrested, the local authorities stuffed ballots for Muslim men, non-members of the independence party.[76] Since the MTLD could not gain independence via elections, Hadj turned to violent means and consulted "the head of its parliamentary wing, Hocine A ̈ıt Ahmed, to advise on how the party might win Algeria's independence through force of arms.[76]" A ̈ıt Ahmed had never been formally trained in strategy, so he studied former rebellions against the French and he came to the conclusion that "no other anti-colonial movement had had to deal with such a sizable and politically powerful settler population.[76]" Due to the powerful settler population, A ̈ıt Ahmed believed that Algeria could only achieve independence if the movement became relevant in the international political arena.[76] Over the next few years, members of the MTLD began to disagree about which direction the organization should go to achieve independence, so eventually the more radical members broke off to form the National Liberation Front (FLN).[76]

Fight for independence in the international arena

The FLN officially started the Algerian War for Independence and followed A ̈ıt Ahmed's advice by creating tensions in the Franco-American relations.[76] Due to the intensifying global relations, the Algerian War became a "kind of world war—a war for world opinion".[76] In closed-door meetings the United States encouraged France to negotiate with the FLN, but during UN meetings the United States helped France end discussion on Algeria.[76] Ultimately, the strategy of just focusing on superpowers was not successful for Algeria, but once A ̈ıt Ahmed began to exploit international rivalries the Algerian war for independence was successful.[76]

Women in the fight for independence

Thousands of women took part in the war, even on deadly missions.[77] Women took part as "combatants, spies, fundraisers, and couriers, as well as nurses, launderers, and cooks".[77] 3% of all fighters were women, which is roughly equivalent to 11,000 women.[77]

This is a quote of three women who participated in the war: "We had visited the site and noted several possible targets. We had been told to place two bombs, but we were three, and at the last moment, since it was possible, we decided to plant three bombs. Samia and I carried three bombs from the Casbah to Bab el Oued, where they were primed...Each of us placed a bomb, and at the appointed time there were two explosions; one of the bombs was defective and didn't go off.' – Djamila B., Zohra D., and Samia, Algiers, September 1956”.[77]

Outcome

Algeria gained independence on February 20, 1962 when the French government signed a peace accord.[78] Peace in the country did not last long. Shortly after gaining independence, the Algerian Civil War began. The civil war erupted from anger regarding one party rule and ever increasing unemployment rates in Algeria. In October 1988, young Algerian men took to the streets and participated in week-long riots.[79] In addition, the Algerian war for independence inspired liberationists in South Africa.[80] However, the liberationists were unsuccessful in implementing Algerian strategy into their independence movement.[80] The Algerian Independence movement also had a lasting impact on French thought about the relationship between the government and religion.[81]

African nationalism in Portuguese Africa

Portugal built a five-century global empire, starting overseas expansion in the 15th century. Innovations such as the caravel, better navigation tools, and the school at Sagres under Prince Henry the Navigator gave the small Atlantic nation an early lead. Explorers reached islands like Madeira and the Azores, pushed down the African coasts, and arrived in Asia, including Japan, by the 16th century. Portugal established forts and colonies across Africa, including Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, and territory around the Congo River such as Cabinda, Luanda, and Benguela. On the southeast coast, they controlled ports like Mozambique, Quelimane, and Lourenço Marques until Arab rivals from Oman took northern territories.

Weaknesses soon emerged. Portugal’s small population and limited popular support meant few settlers, and convict exiles were sent to places like Angola. African economies under Portuguese control became dependent on the Atlantic slave trade, especially to Brazil. Although slavery was outlawed in stages, ending in 1858, powerful interests delayed change. Political instability at home during and after the Napoleonic Wars hindered colonial governance. Meanwhile, the Industrial Revolution increased European demand for African resources. Britain, tied to Portugal through long diplomatic and economic relations, pushed for free-trade access and often dominated commerce in Portuguese territories. Growing European competition in the 19th century led to disputes over regions such as the Shire Highlands (modern Malawi) and over control around the Congo River. British challenges to vague Portuguese claims set precedents requiring effective occupation, a principle formalised at the Congress of Berlin in 1884–85.

After World War II, Portugal renamed its colonies “Overseas Provinces” and resisted decolonisation. Modernisation followed, particularly in Angola and Mozambique. In the 1960s, nationalist movements, supported by the Eastern Bloc and others, launched liberation struggles. The resulting conflicts in Angola, Guinea, and Mozambique became known as the Portuguese Colonial War.

Portuguese Angola

In Portuguese Angola, the rebellion of the ZSN was taken up by the União das Populações de Angola (UPA), which changed its name to the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) in 1962. On February 4, 1961, the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) took credit for the attack on the prison of Luanda, where seven policemen were killed. On March 15, 1961, the UPA, in a tribal attack, started the massacre of white populations and black workers born in other regions of Angola. This region would be retaken by large military operations that, however, would not stop the spread of the guerrilla actions to other regions of Angola, such as Cabinda, the east, the southeast and the central plateaus.

Portuguese Guinea

In Portuguese Guinea, the Marxist African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) started fighting in January 1963. Its guerrilla fighters attacked the Portuguese headquarters in Tite, located to the south of Bissau, the capital, near the Corubal River. Similar actions quickly spread across the entire colony, requiring a strong response from the Portuguese forces.

The war in Guinea placed face to face Amílcar Cabral, the leader of PAIGC, and António de Spínola, the Portuguese general responsible for the local military operations. In 1965 the war spread to the eastern part of the country and in that same year the PAIGC carried out attacks in the north of the country where at the time only the minor guerrilla movement, the Frente de Luta pela Independência Nacional da Guiné (FLING), was fighting. By that time, the PAIGC started receiving military support from the Socialist Bloc, mainly from Cuba, a support that would last until the end of the war.

In Guinea the Portuguese troops mainly took a defensive position, limiting themselves to keeping the territories they already held. This kind of action was particularly devastating to the Portuguese troops who were constantly attacked by the forces of the PAIGC. They were also demoralised by the steady growth of the influence of the liberation supporters among the population that was being recruited in large numbers by the PAIGC.

With some strategic changes by António Spínola in the late 1960s, the Portuguese forces gained momentum and, taking the offensive, became a much more effective force. Between 1968 and 1972, the Portuguese forces took control of the situation and sometimes carried attacks against the PAIGC positions. At this time the Portuguese forces were also adopting subversive means to counter the insurgents, attacking the political structure of the nationalist movement. This strategy culminated in the assassination of Amílcar Cabral in January 1973. Nonetheless, the PAIGC continued to fight back and pushed the Portuguese forces to the limit. This became even more visible after PAIGC received anti-aircraft weapons provided by the Soviets, especially the SA-7 rocket launchers, thus undermining the Portuguese air superiority.

Portuguese Mozambique

Portuguese Mozambique was the last territory to start the war of liberation. Its nationalist movement was led by the Marxist-Leninist Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO), which carried out the first attack against Portuguese targets on September 24, 1964, in Chai, province of Cabo Delgado. The fighting later spread to Niassa, Tete at the centre of the country. A report from Battalion No. 558 of the Portuguese army makes references to violent actions, also in Cabo Delgado, on August 21, 1964. On November 16 of the same year, the Portuguese troops suffered their first losses fighting in the north of the country, in the region of Xilama. By this time, the size of the guerrilla movement had substantially increased; this, along with the low numbers of Portuguese troops and colonists, allowed a steady increase in FRELIMO's strength. It quickly started moving south in the direction of Meponda and Mandimba, linking to Tete with the aid of Malawi.

Until 1967 the FRELIMO showed less interest in Tete region, putting its efforts on the two northernmost districts of the country where the use of landmines became very common. In the region of Niassa, FRELIMO's intention was to create a free corridor to Zambézia. Until April 1970, the military activity of FRELIMO increased steadily, mainly due to the strategic work of Samora Machel in the region of Cabo Delgado. In the early 1970s, after the Portuguese Gordian Knot Operation, the nationalist guerrilla was severely damaged.

Role of the Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was founded May 1963. Its basic principles were co-operation between African nations and solidarity between African peoples. Another important objective of the OAU was an end to all forms of colonialism in Africa. This became the major objective of the organisation in its first years and soon OAU pressure led to the situation in the Portuguese colonies being brought up at the UN Security Council.

The OAU established a committee based in Dar es Salaam, with representatives from Ethiopia, Algeria, Uganda, Egypt, Tanzania, Zaire, Guinea, Senegal and Nigeria, to support African liberation movements. The support provided by the committee included military training and weapon supplies. The OAU also took action in order to promote the international acknowledgement of the legitimacy of the Revolutionary Government of Angola in Exile (GRAE), composed of the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA). This support was transferred to the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and to its leader, Agostinho Neto in 1967. In November 1972, both movements were recognised by the OAU in order to promote their merger. After 1964, the OAU recognised PAIGC as the legitimate representatives of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde and in 1965 recognised FRELIMO for Mozambique.

Eritrea

Eritrea sits on a strategic location along the Red Sea between the Suez Canal and the Bab-el-Mandeb. Eritrea was an Italian colony from 1890 to 1941. On April 1, 1941, the British captured Asmara defeating the Italians and Eritrea fell under the British Military Administration. This military rule lasted from 1941 until 1952. On December 2, 1950, the United Nations General Assembly, by UN Resolution 390 A(V) federated Eritrea with Ethiopia. The architect of this federal act was the United States. The federation went into effect September 11, 1952. However, the federation was a non-starter for feudal Ethiopia, and it started to systematically undermine it. On December 24, 1958—the Eritrean flag was replaced by the Ethiopian flag; On May 17, 1960—The title "Government of Eritrea" of the Federation was changed to "Administration of Eritrea". Earlier Amharic was declared official language in Eritrea replacing Tigrinya and Arabic. Finally on November 14, 1962 -– Ethiopia officially annexed Eritrea as its 14th province.

The people of Eritrea, after finding out peaceful resistance against Ethiopia's rule was falling on deaf ears formed the Eritrean Liberation Movement in 1958. The founders of these independence movement were: Mohammad Said Nawud, Saleh Ahmed Iyay, Yasin al-Gade, Mohammad al-Hassen and Said Sabr. ELM members were organised in secret cells of seven. The movement was known as Mahber Shewate in Tigrinya and as Harakat Atahrir al Eritrea in Arabic. On July 10, 1960, a second independence movement, the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) was founded in Cairo. Among its founders were: Idris Mohammed Adem, President, Osman Salih Sabbe, Secretary General, and Idris Glawdewos as head of military affairs. These were among those who made up the highest political body known as the Supreme Council. On September 1, 1961, Hamid Idris Awate and his ELF unit attacked an Ethiopian police unit in western Eritrea (near Mt. Adal). This heralded the 30-year Eritrean war for independence. Between March and November 1970, three core groups that later made up the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) split from the ELF and established themselves as separate units.

In September 1974, Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown by a military coup in Ethiopia. The military committee that took power in Ethiopia is better known by its Amharic name the Derg. After the military coup the Derg broke ties with the U.S. and aligned with the Soviet Union, and the Soviet Union and its eastern bloc allies replaced the United States as patrons of Ethiopia's aggression against Eritrea. Between January and July 1977, the ELF and EPLF armies had liberated 95% of Eritrea, capturing all but 4 towns. However, in 1978–79, Ethiopia mounted a series of five massive Soviet-backed offensives and reoccupied almost all of Eritrea's major towns and cities, except for Nakfa. The EPLF withdrew to a mountain base in northern Eritrea, around the town of Nakfa. In 1980 the EPLF had offered a proposal for referendum to end the war, however, Ethiopia, thinking it had a military upper hand, rejected the offer and war continued. In February–June 1982, The EPLF managed to repulse Ethiopia's much heralded four-month "Red Star" campaign, also known as the 6th offensive by Eritreans, inflicting more than 31,000 Ethiopian casualties.

In 1984, the EPLF launched a counter-offensive and cleared the Ethiopian from the Northeastern Sahil front. In March 1988, the EPLF demolished the Ethiopian front at Afabet in a major offensive the British Historian Basil Davidson compared to the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu. In February 1990, the EPLF liberated the strategic port of Massawa, and in the process destroyed a portion of the Ethiopian Navy. A year later, the war came to conclusion on May 24, 1991, when the Ethiopian army in Eritrea surrendered. Thus Eritrea's 30-year war crowned with victory.

On May 24, 1993, after a UN-supervised referendum on April 23–25, 1993, in which the Eritrean people overwhelmingly, 99.8%, voted for independence, Eritrea officially declared its independence and gained international recognition.

Namibia

At the onset of World War I, the Union of South Africa participated in the invasion and occupation of several Allied territories taken from the German Empire, most notably German South West Africa and German East Africa in present-day Tanzania. Germany's defeat forced the new Weimar Republic to cede its overseas possessions to the League of Nations as mandates. A mandate over South-West Africa was conferred upon the United Kingdom, "for and on behalf of the government of the Union of South Africa", which was to handle administrative affairs under the supervision of the league. South-West Africa was classified as a "C" mandate, or a territory whose population sparseness, small size, remoteness, and geographic continuity to the mandatory power allowed it to be governed as an integral part of the mandatory itself. Nevertheless, the League of Nations obliged South Africa to promote social progress among indigenous inhabitants, refrain from establishing military bases there, and grant residence to missionaries of any nationality without restriction. Article 7 of the South-West Africa mandate stated that the consent of the league was required for any changes in the terms of the mandate.

With regards to the local German population, the occupation was on especially lenient terms; South Africa only repatriated civil and military officials, along with a small handful of political undesirables. Other German civilians were allowed to remain. In 1924 all white South-West Africans were automatically naturalised as South African nationals and British subjects thereof; the exception being about 260 who lodged specific objections. In 1926 a Legislative Assembly was created to represent German, Afrikaans, and English-speaking white residents. Control over basic administrative matters, including taxation, was surrendered to the new assembly, while matters pertaining to defence and native affairs remained in the hands of an administrator-general.

Following World War II, South West Africa's international status after the dissolution of the League of Nations was questioned. The United Nations General Assembly refused South Africa permission to incorporate the mandate as a fifth province, largely due to its controversial policy of racial apartheid. At the General Assembly's request the issue was examined at the International Court of Justice. The court ruled in 1950 that South Africa was not required to transfer the mandate to UN trusteeship, but remained obligated to adhere to its original terms, including the submission of annual reports on conditions in the territory.

Led by newly elected Afrikaner nationalist Daniel François Malan, the South African government rejected this opinion and refused to recognise the competence of the UN to interfere with South-West African affairs. In 1960 Ethiopia and Liberia, the only two other former League of Nations member states in Africa, petitioned the Hague to rule in a binding decision that the league mandate was still in force and to hold South Africa responsible for failure to provide the highest material and moral welfare of black South West Africans. It was pointed out that nonwhite residents were subject to all the restrictive apartheid legislation affecting nonwhites in South Africa, including confinement to reserves, colour bars in employment, pass laws, and "influx control" over urban migrants. A South African attempt to scupper proceedings by arguing that the court had no jurisdiction to hear the case was rejected; conversely, however, the court itself ruled that Ethiopia and Liberia did not possess the necessary legal interest entitling them to bring the case.

In October 1966 the General Assembly declared that South Africa had failed to fulfill its obligations as the mandatory power and had in fact disavowed them. The mandate was unilaterally terminated on the grounds that the UN would now assume direct responsibility for South-West Africa. In 1967 and 1969 the UN called for South Africa's disengagement and requested the Security Council to take measures to oust the South African Defence Force from the territory that the General Assembly, at the request of black leaders in exile, had officially renamed Namibia. One of the greatest aggravating obstacles to eventual independence occurred when the UN also agreed to recognise the South West African People's Organization (SWAPO), then an almost exclusively Ovambo body, as the sole authentic representative of the Namibian population. South Africa was offended by the General Assembly's simultaneous dismissal of its various internal Namibian parties as puppets of the occupying power. Furthermore, SWAPO espoused a militant platform which called for independence through UN activity, including military intervention.

By 1965 SWAPO's morale had been elevated by the formation of a guerrilla wing, the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), which forced the deployment of South African Police troops along the long and remote northern frontier. The first armed clashes between PLAN cadres and local security forces took place in August 1966.

Legacy

An extensive body of literature has examined the legacy of colonialism and colonial institutions on economic outcomes in Africa, with numerous studies showing disputed economic effects .[82] Modernisation theory posits that colonial powers built infrastructure to integrate Africa into the world economy; however, this was built mainly for extraction purposes. African economies were structured to benefit the coloniser and any surplus was likely to be 'drained', thereby stifling local capital accumulation.[83] Dependency theory suggests that most African economies continued to occupy a subordinate position in the world economy after independence with a reliance on primary commodities such as copper in Zambia and tea in Kenya.[84] Despite this continued reliance and unfair trading terms, a meta-analysis of 18 African countries found that a third of them experienced increased economic growth post-independence.[83]

Scholars including Dellal (2013), Miraftab (2012) and Bamgbose (2011) have argued that Africa's linguistic diversity has been eroded.[full citation needed] Language has been used by western colonial powers to divide territories and create new identities, which have led to conflicts and tensions between African nations.[85] In the immediate post-independence period, African countries largely retained colonial legislation. However, by 2015 much colonial legislation had been replaced by laws that were written locally.[86]

Notes

- ^ Explanatory notes are added in cases where decolonisation was achieved jointly by multiple countries or where the current country is formed by the merger of previously decolonised countries. Although Ethiopia was administered as a colony in the aftermath of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War and was recognized by the international community as such at the time, it is not listed here as its brief period under Italian rule (which lasted for a little more than five years and ended with the return of the previous native government) is now usually seen as a military occupation.

- ^ Some territories changed hands multiple times, so only the last colonial power is mentioned in the list. In addition, the mandatory or trustee powers are mentioned for territories that were League of Nations mandates and UN Trust Territories.

- ^ The dates of decolonisation for territories annexed by or integrated into previously decolonised independent countries are given in separate notes, as are dates when a Commonwealth realm abolished its monarchy.

- ^ For countries that became independent either as a Commonwealth realm, a monarchy with a strong Prime Minister, or a parliamentary republic, the head of government is listed instead.

- ^ As Union of South Africa.

- ^ The Union of South Africa was constituted through the South Africa Act entering into force on 31 May 1910. On 11 December 1931, it got increased self-governance powers through the Statute of Westminster which was followed by transformation into a republic after the 1960 referendum. Afterwards, South Africa was under apartheid until elections resulting from the negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa on 27 April 1994 when Nelson Mandela became president.

- ^ As the Kingdom of Egypt. Transcontinental country, partially located in Asia.

- ^ On 28 February 1922 the British government issued the Unilateral Declaration of Egyptian Independence. Through this declaration, the British government unilaterally ended its protectorate over Egypt and granted it nominal independence except four "reserved" areas: foreign relations, communications, the military, and the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.[33] The Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936 reduced British involvement, but still was not welcomed by Egyptian nationalists, who wanted full independence from Britain, which was not achieved until 23 July 1952. The last British troops left Egypt after the Suez Crisis of 1956.

- ^ Although the leaders of the 1952 revolution (Mohammed Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser) became the de facto leaders of Egypt, neither would assume office until 17 September of that year when Naguib became Prime Minister, succeeding Aly Maher Pasha who was sworn in on the day of the revolution. Nasser would succeed Naguib as Prime Minister on 25 February 1954.

- ^ As the United Kingdom of Libya.

- ^ From 1947, Libya was administrated by the Allies of World War II (the United Kingdom and France). Part of the British Military Administration originally gained independence as the Cyrenaica Emirate; it was only recognized by the United Kingdom. The Cyrenaica Emirate also merged to form the United Kingdom of Libya.

- ^ Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement of 1899, stated that Sudan should be jointly governed by Egypt and Britain, but with real power remaining in British hands.[35]

- ^ Before Sudan even gained its independence, on 18 August 1955 the southern area of Sudan began fighting for greater autonomy. After the signing of the Addis Ababa Agreement on 28 February 1972, South Sudan was granted autonomous rule. On 5 June 1983, however, the Sudan government revoked this autonomous rule, igniting a new war for control of South Sudan. (The main non-government combatant of the Second Sudanese Civil War largely claimed to be fighting for a united, secular Sudan rather than South Sudan's independence.) On 9 July 2005, following the Comprehensive Peace Agreement signed on 9 January of that year, the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region was restored; exactly six years later, in the aftermath of the 9–15 January 2011 South Sudanese independence referendum, South Sudan became independent.

- ^ Salva Kiir Mayardit became President of South Sudan upon independence. Abel Alier was the first President of the High Executive Council of the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region, while John Garang became its President following its restoration.

- ^ Sudan's independence is indirectly linked to the Egyptian revolution of 1952, whose leaders eventually denounced Egypt's claim over Sudan. (This revocation would force the British to end the condominium.)

- ^ As the Kingdom of Tunisia.

- ^ See Tunisian independence.

- ^ Cape Juby was ceded by Spain to Morocco on 2 April 1958. Ifni was returned from Spain to Morocco on 4 January 1969.

- ^ As the Dominion of Ghana.

- ^ The British Togoland mandate and trust territory was integrated into Gold Coast colony on 13 December 1956. On 1 July 1960 Ghana formally abolished its Commonwealth monarchy and became a republic.

- ^ a b c d Originally as Prime Minister; became President upon the monarchy's abolition.

- ^ After the French Cameroun mandate and trust territory gained independence it was joined by part of the British Cameroons mandate and trust territory on 1 October 1961. The other part of British Cameroons joined Nigeria.

- ^ Minor armed insurgency from Union of the Peoples of Cameroon.

- ^ Senegal and French Sudan gained independence on 20 June 1960 as the Mali Federation, which dissolved a few months later into present-day Senegal and Mali.

- ^ As the Malagasy Republic.

- ^ The Malagasy Uprising was an earlier armed uprising that failed to gain independence from France.

- ^ As the Republic of the Congo.

- ^ The Congo Crisis occurred after independence.

- ^ As the Somali Republic.

- ^ The Trust Territory of Somalia (former Italian Somaliland) united with the State of Somaliland (former British Somaliland) on 1 July 1960 to form the Somali Republic (Somalia).

- ^ As the Republic of Dahomey.

- ^ As Upper Volta.

- ^ Part of the British Cameroons mandate and trust territory on 1 October 1961 joined Nigeria. The other part of British Cameroons joined the previously decolonised French Cameroun mandate and territory.

- ^ a b After both gained independence Tanganyika and Zanzibar merged on 26 April 1964 as Tanzania.

- ^ As the Kingdom of Burundi.

- ^ Assumed office on 27 September 1962, as Prime Minister. From the date of independence to Ben Bella's inauguration, Abderrahmane Farès served as President of the Provisional Executive Council.

- ^ Abolished its commonwealth monarchy exactly one year later; Jamhuri Day ("Republic Day") is a celebration of both dates.

- ^ The Mau Mau Uprising was an earlier armed uprising that failed to gain independence from the United Kingdom.

- ^ The Sultanate of Zanzibar would later be overthrown within a month of sovereignty by the Zanzibar Revolution.

- ^ Abolished its commonwealth monarchy exactly two years later.

- ^ Abolished its commonwealth monarchy on 24 April 1970.

- ^ Due to Rhodesia's unwillingness to accommodate the British government's request for black majority rule, the United Kingdom (along with the rest of the international community) refused to recognize the white-minority-led government. The former self-governing colony would not be recognized as an independent state until the aftermath of the Rhodesian Bush War, under the name Zimbabwe.

- ^ Botswana Day Holiday is the second day of the two-day celebration of Botswana's independence. The first day is also referred to as Botswana Day.

- ^ Moshoeshoe II became King upon independence.

- ^ After the French Cameroun mandate and trust territory gained independence it was joined by part of the British Cameroons mandate and trust territory on 1 October 1961. The other part of British Cameroons joined Nigeria.

- ^ Not celebrated as a holiday. The date 24 September 1973 (when the PAIGC formally declared Guinea's independence) is celebrated as Guinea-Bissau's date of independence.

- ^ As the People's Republic of Mozambique

- ^ Pedro Pires was sworn in as Prime Minister three days after independence.

- ^ Although the fight for Cape Verdean independence was linked to the liberation movement occurring in Guinea-Bissau, the island country itself saw little fighting.

- ^ As the People's Republic of Angola

- ^ The Spanish colonial rule de facto terminated over the Western Sahara (then Spanish Sahara), when the territory was passed on to and partitioned between Mauritania and Morocco (which annexed the entire territory in 1979). The decolonisation of Western Sahara is still pending, while a declaration of independence has been proclaimed by the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic, which controls only a small portion east of the Moroccan Wall. The UN still considers Spain the legal administrating country of the whole territory,[37] awaiting the outcome of the ongoing Manhasset negotiations and resulting election to be overseen by the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara. However, the de facto administrator is Morocco (see United Nations list of non-self-governing territories).

- ^ Liberia would later annex the Republic of Maryland, another settler colony made up of former African-American slaves, in 1857. Liberia would not be recognized by the United States until 5 February 1862.

- ^ Stephen Allen Benson was President on the date of the United States' recognition.

- ^ Not celebrated as a holiday. The date 24 September 1973 (when the PAIGC formally declared Guinea's independence) is celebrated as Guinea-Bissau's date of independence.

- ^ Not celebrated as a holiday. The date 24 September 1973 (when the PAIGC formally declared Guinea's independence) is celebrated as Guinea-Bissau's date of independence.

See also

- History of Africa#1951 – present

- Postcolonial Africa

- Economic history of Africa

- List of European colonies in Africa

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories in Africa

- States and Power in Africa

- Africa–United States relations

- Wars of national liberation

- Women in the decolonisation of Africa

- Year of Africa

References

- ^ Hatch 1967.

- ^ Gifford & Louis 1982.

- ^ Birmingham 1995.

- ^ Hargreaves 1996.

- ^ for the viewpoint from London and Paris see von Albertini 1971.

- ^ Appiah, Anthony; Gates Jr., Henry Louis (2010). Berlin Conference of 1884-1885. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Berlin Conference". teacherweb.ftl.pinecrest.edu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "The Revolutionary Summer of 1862". National Archives. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Adwa Day in Ethiopia | Tesfa Tours". www.tesfatours.com. 2 March 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Fascismo: guerra d'Etiopia". www.storiaxxisecolo.it. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ a b Hunt, Michael (2017). The World Transformed: 1945 to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-19-937102-0.

- ^ a b c "Decolonisation of Africa". selfstudyhistory.com. 25 January 2015. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018.

- ^ Manela, Erez (1 December 2006). "Imagining Woodrow Wilson in Asia: Dreams of East-West Harmony and the Revolt against Empire in 1919". American Historical Review. 111 (5): 1327–1351. doi:10.1086/ahr.111.5.1327. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Africans played key, often unheralded, role in World War I". AP News. 1 December 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ Killingray, David (2010). Fighting for Britain : African soldiers in the Second World War. Martin Plaut. Woodbridge, Suffolk: James Currey. ISBN 978-1-84615-789-9. OCLC 711105036.

- ^ a b "Africa's Role in WWII Remembered - Fifteen Eighty Four | Cambridge University Press". 25 August 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Ferguson, Ed, and A. Adu Boahen. (1990). "African Perspectives On Colonialism." The International Journal Of African Historical Studies 23 (2): 334. doi:10.2307/219358.

- ^ "The Atlantic Conference & Charter, 1941". history.state.gov. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

The Atlantic Charter was a joint declaration released by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill on August 14, 1941, following a meeting of the two heads of state in Newfoundland.

- ^ Karski, Jan (2014). The Great Powers and Poland: From Versailles to Yalta. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-4422-2665-4. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Winston Churchill (9 September 1941). "War Situation". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 374. Parliament of the United Kingdom: Commons. col. 69.

- ^ Franklin D. Roosevelt (20 October 2016). "Fireside Chat 20: On the Progress of the War". Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Reeves, Mark (10 August 2017). "'Free and Equal Partners in Your Commonwealth': The Atlantic Charter and Anticolonial Delegations to London, 1941–3". Twentieth Century British History. 29 (2): 259–283. doi:10.1093/tcbh/hwx043. ISSN 0955-2359. PMID 29800336.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". United Nations. 1948. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Kelly, Saul (1 September 2000). "Britain, the united states, and the end of the Italian empire in Africa, 1940–52". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 28 (3): 51–70. doi:10.1080/03086530008583098. ISSN 0308-6534. S2CID 159656946.

- ^ Assa, O. (2006). A History of Africa. Volume 2. Kampala East Africa Education Publisher ltd.

- ^ "Declaration on the granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples". undocs.org. 14 December 1960. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ [Boahen, A. (TND) (1990) Africa Under Colonial Domination, Volume 7]

- ^ Kendhammer, Brandon (1 January 2007). "DuBois the pan-Africanist and the development of African nationalism". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 30 (1): 51–71. doi:10.1080/01419870601006538. ISSN 0141-9870. S2CID 55991352.

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Agbo, Chukwuemeka (2018), Shanguhyia, Martin S.; Falola, Toyin (eds.), "Nationalism and African Intellectuals", The Palgrave Handbook of African Colonial and Postcolonial History, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 621–641, doi:10.1057/978-1-137-59426-6_25, ISBN 978-1-137-59426-6, retrieved 2 December 2021

- ^ Fleshman, Michael (August 2010). "A 'Wind Of Change' That Transformed The Continent". United Nations. Africa Renewal. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019.

- ^ "Atlantic Charter", 14 August 1941, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_16912.htm Archived 8 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James Hunter Meriwether, Tears, Fire, and Blood: The United States and the Decolonization of Africa (University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

- ^ wucher King, Joan (1989) [First published 1984]. Historical Dictionary of Egypt. Books of Lasting Value. American University in Cairo Press. pp. 259–260. ISBN 978-977-424-213-7.

- ^ "A/RES/289(IV) - E - A/RES/289(IV)". undocs.org. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Robert O. Collins, A History of Modern Sudan Archived 18 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Independent Benin unilaterally annexed Portuguese São João Baptista de Ajudá in 1961.

- ^ UN General Assembly Resolution 34/37 and UN General Assembly Resolution 35/19

- ^ UN resolution 2145 terminated South Africa's mandate over Namibia, making it de jure independent. South Africa did not relinquish the territory until 1990

- ^ Schiller, A. Arthur (1 July 1953). "Eritrea: Constitution and Federation with Ethiopia". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 2 (3): 375–383. doi:10.2307/837485. JSTOR 837485 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ Esseks, John D. "Political independence and economic decolonisation: the case of Ghana under Nkrumah." Western Political Quarterly 24.1 (1971): 59-64.

- ^ Nkrumah, Kwame, Fifth Pan-African Congress, Declaration to Colonial People of the World (Manchester, England, 1945).

- ^ "POLITICAL PARTY ACTIVITY IN GHANA—1947 TO 1957 - Government of Ghana". www.ghana.gov.gh. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ Daniel Yergin; Joseph Stanislaw (2002). The Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy. Simon and Schuster. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-684-83569-3.

- ^ Frank Myers, "Harold Macmillan's" Winds of Change" Speech: A Case Study in the Rhetoric of Policy Change." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 3.4 (2000): 555-575. excerpt Archived 20 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Philip E. Hemming, "Macmillan and the End of the British Empire in Africa." in R. Aldous and S. Lee, eds., Harold Macmillan and Britain's World Role (1996) pp. 97-121, excerpt Archived 5 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James, pp. 618–21.

- ^ "Chagos Deal Is Done: Sovereignty Is Returned to Mauritius". e-ir.info. 25 May 2025. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ "Belgium's role in Rwandan genocide". Le Monde Diplomatique. 1 June 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Cowan, L. Gray (1964). The Dilemmas of African Independence. New York: Walker & Company, Publishers. pp. 42–55, 105. ASIN B0007DMOJ0.

- ^ Patrick Manning, Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa 1880-1995 (1998) pp 135-63.

- ^ Guy De Lusignan, French-speaking Africa since independence (1969) pp 3-86.

- ^ Rudolph von, Decolonization: the Administration and Future of the Colonies, 1919-1960 (1971), 265-472.

- ^ Brazzaville: 30 janvier–8 fevrier 1944. Ministere des Colonies. 1944. p. 32. Quoted in: Smith, Tony (1978). "A Comparative Study of French and British Decolonization". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 20 (1): 73. doi:10.1017/S0010417500008835. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 178322. S2CID 145080475.

- ^ Horne, Alistair (1977). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962. New York: The Viking Press. p. 27.

- ^ J.F.V. Keiger, France and the World since 1870 (Arnold, 2001) p 207.

- ^ Anthony Clayton, The Wars of French Decolonization (1994) p 85

- ^ Weigert, Stephen L., ed. (1996), "Cameroon: The UPC Insurrection, 1956–70", Traditional Religion and Guerrilla Warfare in Modern Africa, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 36–48, doi:10.1057/9780230371354_4, ISBN 978-0-230-37135-4, retrieved 23 April 2021

- ^ Martin S. Alexander; et al. (2002). Algerian War and the French Army, 1954–62: Experiences, Images, Testimonies. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-230-50095-2.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker, ed. (2018). The Roots and Consequences of Independence Wars: Conflicts that Changed World History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 355–57. ISBN 978-1-4408-5599-3.

- ^ James McDougall, "The Impossible Republic: The Reconquest of Algeria and the Decolonization of France, 1945–1962", Journal of Modern History 89#4 (2017) pp 772–811 excerpt Archived 22 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Algeria celebrates 50 years of independence - France keeps mum". RFI. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ "The Evian Accords and the Algerian War: An Uncertain Peace". origins.osu.edu. 15 March 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "French-Algerian truce". HISTORY. 9 February 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Julian Jackson, De Gaulle (2018), pp 490-93, 525, 609-615.

- ^ Dorothy Shipley White, Black Africa and de Gaulle: From the French Empire to Independence (1979).

- ^ Robert Aldrich, Greater France: A history of French overseas expansion (1996) pp 303–6

- ^ "Mayotte votes to become France's 101st département Archived 5 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine". The Daily Telegraph. 29 March 2009.

- ^ Oliveira, Pedro Aires (24 May 2017). "Decolonization in Portuguese Africa". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.41. ISBN 9780190277734. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Flight from Angola, The Economist (16 August 1975).

- ^ Dismantling the Portuguese Empire, Time Magazine (Monday, 7 July 1975).

- ^ a b Kara, Siddharth (1 January 2023). Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives. St. Martins Press. ISBN 978-1-250-28429-7.

- ^ Morgan, Philip D. (2011). "Lowcountry Georgia and the Early Modern Atlantic World, 1733-ca. 1820". In Morgan, Philip D. (ed.). African American Life in the Georgia Lowcountry: The Atlantic World and the Gullah Geechee. Race in the Atlantic World, 1700-1900 Series. University of Georgia Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8203-4307-5. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

[...] Georgia represented a break from the past. As one scholar has noted. it was 'a preview of the later doctrines of "systematic colonization" advocated by Edward Gibbon Wakefield and others for the settlement of Australia and New Zealand.' In contrast to such places as Jamaica and South Carolina, the trustees intended Georgia as 'a regular colony', orderly, methodical, disciplined [...]

- ^ "Tomasz Kamusella. 2020. Global Language Politics: Eurasia versus the Rest (pp 118-151). Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics. Vol 14, No 2".

- ^ a b Myrice, Erin (2015). ""The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa"". Bowling Green State University.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Alghailani, Said Ali (2002). Islam and the French Decolonization of Algeria: The Role of the Algerian Ulama, 1919–1940 (Thesis). OCLC 52840779.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Connelly, Matthew (2001). "Rethinking the Cold War and Decolonization: The Grand Strategy of the Algerian War for Independence". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 33 (2): 221–245. doi:10.1017/S0020743801002033. S2CID 203337150.

- ^ a b c d Turshen, Meredeth (2002). "Algerian Women in the Liberation Struggle and the Civil War: From Active Participants to Passive Victims?". Social Research: An International Quarterly. 69 (3): 889–911. doi:10.1353/sor.2002.0047. JSTOR 40971577. S2CID 140869532. Gale A94227145 Project MUSE 558536 ProQuest 209667669.

- ^ Cairns, John C. (June 1962). "Algeria: The Last Ordeal". International Journal: Canada's Journal of Global Policy Analysis. 17 (2): 87–97. doi:10.1177/002070206201700201. S2CID 144891906.

- ^ Saleh, Heba; Witt, Sarah (4 March 2019). "Timeline: Algeria's 30 Turbulent Years". Financial Times.