Urukagina

| Urukagina 𒌷𒅗𒄀𒈾 | |

|---|---|

| King of Lagash | |

| Reign | c. 2378 – c. 2368 BC |

| Predecessor | Lugalanda |

| Successor | Possibly Meszi |

| Died | c. 2368 BC |

| Issue | Subur-Ba-ba |

| Dynasty | 1st Dynasty of Lagash |

| Religion | Sumerian religion |

Uru-ka-gina, Uru-inim-gina, Eri-enim-ge-na, or Iri-ka-gina (Sumerian: 𒌷𒅗𒄀𒈾 URU-KA-gi.na; died c. 2368 BC) ruled in the 24th century BC as King of the city-states of Lagash and Girsu in Mesopotamia, and was the last ruler of the 1st Dynasty of Lagash.[1] He assumed the kingship, claiming to be divinely appointed, following the reign of his predecessor Lugalanda. It is generally thought that Lugalanda lived on for 4 or 5 years after the ascension of Urukagina with the title "ensi-gal".[2] The wife of Urukagina was named Sagsag, and a statue of her in the temple of Baba in Lagash was still being venerated centuries later in the Ur III dynasty.[3] When Baranamtarra, the wife of Lugalanda, died in the 2nd year of Urukagina's reign, Sagsag was responsible for the funeral and repeated memorial rites. The funeral included "177 slave-girls, 92 lamentation singers, and 48 ‘wives of elders (?)’, who participated on two consecutive days at the ‘place of mourning’ (ki.ḫul)".[4]

In the later half of his reign, Lagash fought wars against its traditional rival city of Umma, under the rule of Lugal-Zage-Si. In the end, Lagash was destroyed and Urukagina retreated to rule at Girsu. The destruction of Lagash was described in a later lament: "the men of Umma ... committed a sin against Ningirsu. ... Offence there was none in Urukagina, king of Girsu, but as for Lugal-Zage-Si, governor of Umma, may his goddess Nisaba make him carry his sin upon his neck".[5] Lugal-Zage-Si himself was soon defeated and his kingdom was annexed by Sargon of Akkad.

History

[edit]

It is known that Urukagina was part of the Lagash structure before assuming rulership based on several text from the reign of his predecessor. In those texts his title, under the name Uru-ka, is ugula-uku3, a high military commander. It has been suggested that his father's name was Ur-Utu. Engilsa has also been proposed but this has been refuted.[6][7][8] Urukagina had a son named Šubur-dBa-ba6.[9] Based on textual sources, it is thought that Urukagina had another son and also two daughters, named Game2-dBa-ba6 andGeme2-tar-sir2-sir2.[10]

In what is generally considered the first year of his reign, he had the title of ensi (governor). In a text following the 4th and 5th year of his predecessor as ruler Lugalanda.

"... A total of 21 1 /4 shekels of pure silver, silver of the bar duba-obligation, being of the fifth and sixth years, Eniggal, the temple steward, assumed. At the (time of) combing full-grown sheep he delivered it to Sasag, the wife of Urukagina, the governor of Lagash"[11]

It is generally assumed that Lugalanda died very late in his 6th year or very early in his 7th year. In this early period, there was no term for a partial regnal year. In succeeding years, Urukagina took the title of lugal (king). Lugalanda appears to have had no male offspring. He is known to have had one brother, Ur-silasirsir, generally thought to have died in the first regnal year of Urukagina.[13] The manner of Urukagina coming to rulership has been long debated. Earlier it was thought that he took power by overthrowing the prior administration. There is no indication of that and Urukagina regularly made offerings to the spirits of Lugalanda and his family including wife Barag-namtara, his father En-entarzi, his grandfather Dudu, and brother Ur-silasirsir and paid respects to MesanDU, who was the personal god of Lugalanda’s family.[14][15]

Urukagina conducted a wide ranging civic and religious building program constructing a number of temples and other cultic sites.

"For Nanshe, (Uruinim-gina) dug her beloved canal, the Ninadua-canal, building the Eninnu at its inlet and the Esirara at its outlet"[16]

as well as infrastructure projects "He built [the reservoir] of the Nimin-DU canal. He built it for him out of 432,000 fired bricks and 1,820 standard gur (2649.6 hl.) of bitumen".[17]

The cites of Umma and Lagash had long been in conflict. Somewhere about the midpoint of the reign of Urukagina, Umma entered an expansionist phase and its ruler, Lugalzagesi, had himself declared King of all Sumer by the priests of Enlil in Nippur. After attempts at diplomacy a long war began with neither side gaining an upper hand. Finally, Lugalzagesi, prevailed apparently by changing to a strategy of destroying holy sites.[18][19][20]

"From (the statue of) Amageshtinana (the leader of Umma) removed her precious metals and lapis lazuli, and threw them in a well. In the fields of Ningirsu, whichever were under cultivation, he crushed the barley"[16]

Towards the end of his 10 or 11 year reign (Lagash I regnal years were marked by numbers rather than "year names" and "year 10" tablets have been found) Lagash, particularly its religious sites, was attacked and devastated by Lugalzagesi, ruler of Umma. Urukagina then changed his title to King of Girsu.[22] A movement in population at the time to Girsu, 25 kilometers to the north, is reflected in the archaeology.[23]

There has long been speculation that Urukagina is mentioned on the Manishtushu Obelisk four times as "Iri-ka-gina, son of Englisa, ensi of Lagash". Manishtushu is generally considered to be the 3rd ruler of the Akkad though one recension of the Sumerian King List has him as the 2nd, after Sargon of Akkad.[24] The chronology of the period is uncertain and it is unclear how much overlap there was between the timeline of northern and southern Mesopotamia so this cannot be ruled out.[25] It has been suggested that Urukagina allied himself with the northerner Sargon and later his sons against Lugal-Zage-Si.[26]

The Sin of Lugalzagesi

[edit]

A 10.2 cm by 9.9 cm by 2.3 cm clay tablet (AO 4162) found at Girsu lists the outrages against the religious establishments of Lagash towards the end of the war by Lugal-Zage-Si. It has been considered a City Lament but lacks many of that types features. The text has been called by many names including "The Sin of Lugalzagesi" and "The Destruction of Lagash" and "Urukagina Lament" and "The Fall of Lagash" and also "Ukg 16".[26]

The majority of the text is a list of the cultic sites despoiled:

"He set fire to the Antasur and bundled off its precious metals and lapis lazuli. He plundered(?) the “palace” of Tiraß, he plundered(?) the Abzu-banda he plundered the chapels of the gods Enlil1 and Utu. He plundered the Ahus and bundled off its precious metals and lapis lazuli he plundered the E-babbar ..."[17]

followed by an indictment of Lugalzagesi:

"The leader of Gissa (Umma), hav[ing] sacked Lagash has committed a sin against the god Nissaba. The hand which he has raised against him will be cut off! It is not a sin of URU-KA-gina, king of Lagash. May Nissaba, the god of Lugal-zage-si ruler of Gissa (Umma), make them (the people of Gissa) bear this sin on their necks!"[17]

Reforms

[edit]

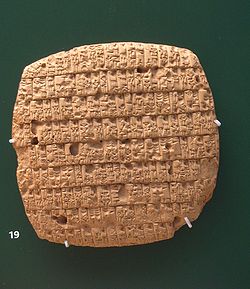

Louvre Museum

AO 3149

There is no solid evidence for a single "reform of Urukagina" or "law code of Urukagina". Rather there are short lists of claims embedded in inscriptions on three rescensions which have differing though related text:[17][28]

The main version has Urukagina as "king of Lagash" dating it to the first two thirds of his reign. Also, it is dated, based on references in the text, to the 2nd year of Urukagina at the latest. Purchased on the antiquities market and thought to come from Girsu.

- AO 3278 - clay foundation cone with a height of 28.2 cm and a base diameter of 16.5 cm

- AO 3149 - clay foundation code with a height of 27 cm and a base diameter of 14.2 cm

- Crozer Theological Seminary no. 5 - a fragment containing only a few lines.

The second version has Urukagina as "King of Girsu" so dates to the later part of his reign. Also, building activities are limited to Girsu, Tiras and Antasur, the later two locations known to have been near to Girsu.

- Clay cone and jar fragments (MNB 1390, AO 12181, AO 12782, IM 5642), found at Tell H at Girsu.

The third is a damaged clay plaque (ES 1717) found at Girsu.

Unfortunately, many of the entries in these texts are obscure and difficult to read and interpret which has resulted in a number of different translations for them being extant.[29][30]

Example of one change in the Reforms

[edit]- Before - When a corpse was brought to the grave, the undertaker took his seven jugs (140 l.) of beer, his 420 loaves of bread, 2 gur (72 l.) of azi-grain, one woolen garment, one lead goat, and one bed. The wailing women took one ul (36 l.) of barley. When a man was brought (for burial) at the “reeds of Enki,” the undertaker took his seven jugs (140 l.) of beer, his 420 loaves of bread, of barley, 2 ul (72 l.) of barley, one wool garment, one bed, and one chair. The old wailing women took one gur (72 l.) of barley.

- After - When a corpse is brought for burial, the undertaker takes his 3 jugs (60 l.) of beer, his 80 loaves of bread, one bed, and one “leading goat” and the wailing women takes 3 ban (18 l.) of barley. When a man is brought for the “reed of Enki,” then the undertaker takes his 4 jugs (80 l.) of beer, his 420 loaves of bread, and one gur (36 l.) of barley, the wailing women take 3 ban (8 l.) of barley and the eres-dingir-priestess takes one lady’s headdress, and one sila (l l.) of aromatic oil.[17]

-

Cone fragment inscribed with part of the text of the reforms of Uruinimgina (Urukagina) - Oriental Institute Museum

-

Reform text of Urukagina, king of Lagash. From Girsu, Iraq. 24th century BC. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul.

-

Reform cone of Urukagina Louvre Museum AO 3278

Some historians assert that the "reforms" of Urukagina were inspired or copied a previous reform that enacted by Entemena:

"[...] Because of the wheat, he sent an envoy to him(Ur-Lumma), and made him say 'You must send my wheat to here!', but Ur-Lumma showed aggressive actions toward this. He said, 'Antasura is mine! It is my border area!' He conscripted the Umma people, and selected (mercenaries) from various countries. On the 'Ugigga' field, which is loved by Ningirsu, the army of Umma was almost annihilated. When the Umma king, Ur-Lumma, retreated, on the basin of the Lumagir-nunta canal, he met 'him'. His donkeys, 60 groups, were left behind, and their individual bones were left on the field."[31][32]

— RIME 1.09.09.03, ex. 01 (P222610), column 4, row 1-30

As Enmetena was the Lagash king who fough Ur-Lumma, and the details of the reform are written on the same plaque, historians, including Kim San-hae has claimed this.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lambert, W. G., "The Reading of the Name Uru.KA.Gi.Na", Orientalia, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 419–419, 1970

- ^ Diakonoff, Igor M., "Some Remarks on the «Reforms» of Urukagina", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 52.1, pp. 1-15, 1958

- ^ Jonker, G.,"The Boundaries of Cultural Memory: The Geographical and Temporal Boundaries Imposed as Conditions for Society’s Past", in The Topography of Remembrance. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 33-70, 1995

- ^ Stol, Marten, "The court and the harem before 1500 BC", Women in the Ancient Near East, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 459-511, 2016

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Schrakamp, Ingo, "Urukagina, Sohn des Engilsa, des Stadtfürsten von Lagaš“: Zur Herkunft des Urukagina, des letzten Herrschers der 1. Dynastie von Lagaš", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 15-23, 2015

- ^ Sallaberger, Walther and Ingo Schrakamp, "Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium", in History & Philology. ARCANE III, edited by Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, pp. 1–136. Turhout: Brepols, 2015

- ^ Schrakamp, Ingo, "Urukagina und die Geschichte von Lagaš am Ende der Präsargonischen Zeit", in It’s a Long Way to a Historiography of the Early Dynastic Period(s), Altertumskunde des Vorderen Orients 15, edited by Reinhard Dittmann, Gebhard J. Selz, and Ellen Rehm, Münster: Ugarit Verlag, pp. 303–385, 2015

- ^ Garcia-Ventura, Agnès and Karahashi, Fumi, "Socio-Economic Aspects and Agency of Female Maš-da-ri-a Contributors in Presargonic Lagash", Women and Religion in the Ancient Near East and Asia, edited by Nicole Maria Brisch and Fumi Karahashi, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 23-44, 2023

- ^ [1]Karahashi, Fumi, "Some Remarks on Women in the Presargonic E2-MI2 Corpus from Lagaš/Girsu", Dissertation, Chuo University, 2018

- ^ Stephens, Ferris J., "Notes on some economic texts of the time of Urukagina", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 49.3, pp. 129-136, 1955

- ^ Transliteration: "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ Balke, Thomas, "Das altsumerische Onomastikon. Namengebung und Prosopografie nach den Quellen aus Lagas", dubsar 1. Münster: Zaphon, 2017

- ^ Steinkeller, Piotr, "Babylonian Priesthood during the Third Millennium BCE: Between Sacred and Profane", JANER 19, pp. 112–151, 2019

- ^ Steinkeller, P., "Urukagina’s Rise to Power", in The IOS Annual Volume 23, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 3-36, 2022

- ^ a b Woods, C.E., "Mu", in The Grammar of Perspective. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 111–160, 2008

- ^ a b c d e Douglas Frayne, "Lagas", in Presargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC), RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia Volume 1, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 77-293, 2008 ISBN 9780802035868

- ^ Westenholz, Aage, "Diplomatic and Commercial Aspects of Temple Offerings as Illustrated by a Newly Discovered Text", Iraq, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 19–21, 1977

- ^ Lambert, Maurice, "La guerre entre Urukagina et Lugalzaggesi", Rivista degli studi orientali 41.Fasc. 1, pp. 29-66, 1966

- ^ H. Hirsch, "Die 'Sunde' Lugalzagesis", Festschrift jiir Wilhelm Eilers, Wiesbaden, pp. 99-106, 1967

- ^ a b Thureau-Dangin, F., "La Ruine de Shirpourla (Lagash): Sous le Règne d'Ouroukagina", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 6.1, pp. 26-32, 1904

- ^ J.S. Cooper, "Reconstructing History from Ancient Inscriptions: The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict", SANE 2/1, Malibu: Undena Publications, 1983

- ^ [2]Goodman, Reed, et al., "The Flooding of Lagash (Iraq): Evidence for Urban Destruction Under Lugalzagesi, the King of Uruk and Umma", Geoarchaeology 40.5, 2025

- ^ P. Steinkeller, "An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List", in Literatur, Politic und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift für Claus Wilcke, ed. W. Sallaberger, K. Volk, and A. Zgoll, pp. 267–92. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2003

- ^ I. J. Gelb, P. Steinkeller, and R. M. Whiting Jr, "OIP 104. Earliest Land Tenure Systems in the Near East: Ancient Kudurrus", Oriental Institute Publications 104 Chicago: The Oriental Institute, 1989, 1991 ISBN 978-0-91-898656-6 Text Plates

- ^ a b Powell, Marvin A., "The sin of Lugalzagesi", Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 86, pp. 307-314, 1996

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1971). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-226-45238-8.

- ^ [3]Karahashi, Fumi, "On the Cultic Aspect of the “Reforms of Urukagina” Changes in the Festival of the Goddess Baba", Orient 55, pp. 63-70, 2020

- ^ Foster, Benjamin, "A New Look at the Sumerian Temple State", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 225–41, 1981

- ^ Pomponio, Francesco, "Urukagina 4 VII 11 and an Administrative Term from the Ebla Texts", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 96–100, 1984

- ^ Kim, San-hae. 최초의 역사 수메르. Humanist Books. ISBN 9791160807684.

- ^ "RIME 1.09.09.03, ex. 01 (P222610)".

Further reading

[edit]- Hruška, Blahoslav, "Die Reformen Urukaginas: Der verspätete Versuch einer Konsolidierung des Stadtstaates von Lagaš", Klio, vol. 57, no. 57, pp. 43-52, 1975

- Foxvog, Daniel A., "A new Lagaš text bearing on Uruinimgina's reforms", Journal of cuneiform studies 46.1, pp. 11-15, 1994

- [4] Hussey, Mary Inda, "Sumerian tablets in the Harvard Semitic Museum. Part I chiefly from the reigns of Lugalanda and Urukagina of Lagash.", Cambridge : Harvard University, 1912

- Kugler, F. X., "Chronologisches und Soziales aus der Zeit Lugalanda’s und Urukagina’s", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 25, no. 3-4, pp. 275-280, 1911

- Lambert, Maurice, "LES «RÉFORMES» D'URUKAGINA", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 50.4, pp. 169-184, 1956

- Lambert, Maurice, "Recherches Sur Les Réformes d’Urukagina", Orientalia, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 22–51, 1975

- Schrakamp, Ingo and Zólyomi, Gábor, "Reevaluating the So-called “Reforms of Urukagina” (2): Their Actual Implementation in the Case of the Maškim Official", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 93-114, 2025

- Steinkeller, Piotr, "The Reforms of UruKAgina and Early Sumerian term for “Prison”", Aula Orientalis: Revista de estudios del Próximo Oriente Antiguo 9.1, pp. 227-233, 1991

- Weidner, Ernst F., "Eine neue Weihbeischrift aus der Zeit ' Urukaginas", Orientalistische Literaturzeitung, vol. 19, no. 1-6, pp. 73-74, 1916