Regency era

| Regency era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1795 – 1837 | |||

| |||

Prince George by Thomas Lawrence (c. 1814) | |||

| Monarch(s) | George III George IV William IV | ||

| Leaders | George, Prince Regent[1] | ||

| English history |

|---|

| Timeline |

The Regency era of British history is commonly understood as the years between c. 1795 and 1837, although the official regency for which it is named only spanned the years 1811 to 1820. King George III first suffered debilitating illness in the late 1780s, and relapsed into his final mental illness in 1810. By the Regency Act 1811, his eldest son George, Prince of Wales, was appointed Prince Regent to discharge royal functions. The Prince had been a major force in Society for decades. When George III died in 1820, the Prince Regent succeeded him as George IV. In terms of periodisation, the longer timespan is roughly the final third of the Georgian era (1714–1837), encompassing the last 25 years or so of George III's reign, including the official Regency, and the complete reigns of both George IV and his brother and successor William IV. It ends with the accession of Queen Victoria in June 1837 and is followed by the Victorian era (1837–1901).

Although the Regency era is remembered as a time of refinement and culture, that was the preserve of the wealthy few, especially those in the Prince Regent's own social circle. For the masses, poverty was rampant as urban population density rose due to industrial labour migration. City dwellers lived in increasingly larger slums, a state of affairs severely aggravated by the combined impact of war, economic collapse, mass unemployment, a bad harvest in 1816 (the "Year Without a Summer"), and an ongoing population boom. Political response to the crisis included the Corn Laws, the Peterloo Massacre, and the Representation of the People Act 1832. Led by William Wilberforce, there was increasing support for the abolitionist cause during the Regency era, culminating in passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

The longer timespan recognises the wider social and cultural aspects of the Regency era, characterised by the distinctive fashions, architecture and style of the period. The period began in the midst of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Throughout the whole period, the Industrial Revolution gathered pace and achieved significant progress by the coming of the railways and the growth of the factory system. The Regency era overlapped with Romanticism and many of the major artists, musicians, novelists and poets of the Romantic movement were prominent Regency figures, such as Jane Austen, William Blake, Lord Byron, John Constable, John Keats, John Nash, Ann Radcliffe, Walter Scott, Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley, J. M. W. Turner and William Wordsworth.

Legislative background

[edit]George III (1738–1820) became King of Great Britain on 25 October 1760 when he was 22 years old, succeeding his grandfather George II. George III had himself been the subject of legislation to provide for a regency when Parliament passed the Minority of Successor to Crown Act 1751 following the death of his father Frederick, Prince of Wales, on 31 March 1751. George became heir apparent at the age of 12 and he would have succeeded as a minor if his grandfather had died before 4 June 1756, George's 18th birthday. As a contingency, the Act provided for his mother, Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales, to be appointed regent and discharge most but not all royal functions.[citation needed]

In 1761, George III married Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and over the following years they had 15 children (nine sons and six daughters). The eldest was Prince George, born on 12 August 1762 as heir apparent. He was named Prince of Wales soon after his birth. By 1765, three infant children led the order of succession and Parliament again passed a Regency Act as contingency. The Minority of Heir to the Crown Act 1765 provided for either Queen Charlotte or Princess Augusta to act as regent if necessary.[citation needed] George III had a long episode of mental illness in the summer of 1788. Parliament proposed the Regency Bill 1789 which was passed by the House of Commons. Before the House of Lords could debate it, the King recovered and the Bill was withdrawn. Had it been passed into law, the Prince of Wales would have become the regent in 1789.[2]

The King's mental health continued to be a matter of concern but, whenever he was of sound mind, he opposed any further moves to implement a Regency Act. Finally, following the death on 2 November 1810 of his youngest daughter, Princess Amelia, he became permanently insane. Parliament passed the Care of King During his Illness, etc. Act 1811, commonly known as the Regency Act 1811. The King was suspended from his duties as head of state and the Prince of Wales assumed office as Prince Regent on 5 February 1811.[3] At first, Parliament restricted some of the Regent's powers, but the constraints expired one year after the passage of the Act.[4] The Regency ended when George III died on 29 January 1820 and the Prince Regent succeeded him as George IV.[5]

After George IV died in 1830, a further Regency Act was passed by Parliament. George IV was succeeded by his brother William IV. His wife, Queen Adelaide, was 37 and there were no surviving legitimate children. The heir presumptive was Princess Victoria of Kent, aged eleven. The new Act provided for her mother, Victoria, Dowager Duchess of Kent to become regent in the event of William's death before 24 May 1837, the young Victoria's 18th birthday. The Act made allowance for Adelaide having another child, either before or after William's death. If the latter scenario had arisen, Victoria would have become Queen only temporarily until the new monarch was born. Adelaide had no more children and, as it happened, William died on 20 June 1837, just four weeks after Victoria was 18.[6]

Perceptions

[edit]Periodisation terminology

[edit]Officially, the Regency began on 5 February 1811 and ended on 29 January 1820 but the "Regency era", as such, is generally perceived to have been much longer. The term is commonly, though loosely, applied to the period from c. 1795 until the accession of Queen Victoria on 20 June 1837.[7] The Regency Era is a sub-period of the longer Georgian era (1714–1837), both of which were followed by the Victorian era (1837–1901). The latter term had contemporaneous usage although some historians give it an earlier startpoint, typically the enactment of the Great Reform Act on 7 June 1832.[8][9][10]

Social, economic and political counterpoints

[edit]The Prince Regent himself was one of the leading patrons of the arts and architecture. He ordered the costly building and refurbishing of the exotic Brighton Pavilion, the ornate Carlton House, and many other public works and architecture. This all required considerable expense which neither the Regent himself nor HM Treasury could afford. The Regent's extravagance was pursued at the expense of the common people.[11]

While the Regency is noted for its elegance and achievements in the fine arts and architecture, there was a concurrent need for social, political and economic change. The country was enveloped in the Napoleonic Wars until June 1815 and the conflict heavily impacted commerce at home and internationally. There was mass unemployment and, in 1816, an exceptionally bad harvest. In addition, the country underwent a population boom and the combination of these factors resulted in rampant poverty. Apart from the national unity government led by William Grenville from February 1806 to March 1807, all governments from December 1783 to November 1830 were formed and led by Tories. Their responses to the national crisis included the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 and the various Corn Laws. The Whig government of Earl Grey passed the Great Reform Act in 1832.[10][12]

Essentially, England during the Regency era was a stratified society in which political power and influence lay in the hands of the landed class. Their fashionable locales were worlds apart from the slums in which the majority of people existed. The slum districts were known as rookeries, a notorious example being St Giles in London. These were places where alcoholism, gambling, prostitution, thievery and violence prevailed.[13] The population boom, comprising an increase from just under a million in 1801 to one and a quarter million by 1820, heightened the crisis.[14] Robert Southey drew a comparison between the squalor of the slums and the glamour of the Regent's circle:[15]

The squalor that existed beneath the glamour and gloss of Regency society provided sharp contrast to the Prince Regent's social circle. Poverty was addressed only marginally. The formation of the Regency after the retirement of George III saw the end of a more pious and reserved society, and gave birth of a more frivolous, ostentatious one. This change was influenced by the Regent himself, who was kept entirely removed from the machinations of politics and military exploits. This did nothing to channel his energies in a more positive direction, thereby leaving him with the pursuit of pleasure as his only outlet, as well as his sole form of rebellion against what he saw as disapproval and censure in the form of his father.

Reform laws

[edit]Great Reform Act of 1832

[edit]The Representation of the People Act 1832 (known as the Great Reform Act) reformed the electoral system in England and Wales and expanded the list of voters. The measure was brought forward by the Whig government of Prime Minister Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey over fierce opposition by the Tory Party, especially in the House of Lords. It granted the right to vote to a broader segment of the male population by standardizing property qualifications, and extending the franchise to small landowners, tenant farmers, shopkeepers, and all householders who paid a yearly rental of £10 or more. The act for England and Wales was accompanied by the Scottish Reform Act 1832 and Irish Reform Act 1832[16][17]

Historians have long grappled with whether it was a radical modernizing movement that introduced democracy or a conservative measure intended to preserve aristocratic rule by making necessary concessions.[18] The terrific battle that produced the 1832 law encouraged reformers, and Parliament passed a series of important reforms in 1833-1841.[19][20]

Social reforms

[edit]The Poor laws were reformed. By the early 19th century, the existing "Old Poor Law" (1601) was criticised as unworkable and too expensive because it primarily used "outdoor relief"—cash aid given to the poor in their homes. Critics argued this practice was overly generous and promoted idleness. In 1834 Parliament therefore passed the Poor Law Amendment Act introducing a radical shift as outdoor relief was largely abolished. The major innovation was the workhouse for full-time confinement. Living conditions within the workhouse were made deliberately worse than the bad conditions faced by paupers. The decentralised parish system was replaced by a centralised structure run by the new "Poor Law Commission" in London. Some 15,000 parishes were grouped into 600 new "Poor Law Unions". The new workhouses were designed to be deliberately grim: families were separated, inmates wore uniforms, performed monotonous labour, and lived under strict discipline. The reforms were met with significant unpopularity and opposition, especially among the working poor in industrial areas. Nevertheless this harsh system remained the primary form of welfare until it was gradually modified and eventually replaced by modern, more humane welfare provisions in the 20th century.[21][22]

The long debate on Emancipation of the British West Indies was climaxed in 1833 with the abolition of slavery in the West Indies colonies to take effect in 1834. Owners were fully compensated, and freed slaves became paid apprentices.[23]

Economic reforms

[edit]The Great Reform Act of 1832, while primarily a political reform, gave industrial towns like Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds representation in Parliament, allowing industrialists and merchants to push for policies favouring economic growth, improved infrastructure, and labour laws.[24] The Factory Acts introduced protections for workers, particularly children.[25]

The powerful farming community fought hard to keep food prices high. The free trade movement finally triumphed in 1846 with the repeal of the Corn Laws . It had a dramatic impact on reshaping the economy.[26]

Municipal government

[edit]Focused on the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835.

Chartism

[edit]Chartism was a large-scale working-class protest movement for political reform that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It was based in industrial cities where workers depended on single industries and were subject to wild swings in economic activity. The main activity was canvassing for petitions with thousands—even millions—of signatures that demanded reform. The petitions demanded six democratic reforms:[27]

- A vote for every man aged 21.

- The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote.

- No property qualification for Members of Parliament.

- Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen and working men to serve.

- Equal constituencies—each with the same number of electors.

- Annual parliamentary elections.

The movement was fiercely opposed by the government, which finally suppressed it. It inspired activists by demonstrating that very large audiences could be mobilized to demand reforms. The first five of its proposals were eventually adopted decades later.[28]

Supporters

[edit]Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey (1764 – 1845) was a Whig politician who served as prime minister from 1830 to 1834. He had primary responsibility for enacting the Reform Acts of 1832, the 1833 Factory Act, the 1834 Poor Law, and the abolition of slavery. He steered a middle course, promoting multiple reforms with very thin majorities while sidetracking the radical Whigs.[29][30] Second in importance was Lord John Russell (1792–1878), who was active in many reforms in his long career.[31]

The first Anti–Corn Law Association was set up in London in 1836. By 1838 the nationwide League, combining all such local associations, was founded, with Richard Cobden and John Bright among its leaders. At the popular level the well-organized Anti-Corn Law League called for lower food prices. After 1845 they emphasized the disastrous potato famine in Ireland.[32][33]

Opponents

[edit]The opponents of reform were a diverse group, based largely in the Tory Party and traditional landed gentry.[34] In Parliament the opponents of reform were known as "Ultra-Tories." The Duke of Wellington was personally inclined against reform, but he saw the need to support moderate reforms. Likewise Robert Peel, the next Tory leader, was highly distrustful of popular agitation. He typically opposed the passage of a new reform, but accepted it after it became law.[35]

The arts

[edit]Architecture

[edit]After the Napoleonic wars ended architecture flourished.[36]

Regent's Park and London Zoo

[edit]In the 1810s, the Prince Regent proposed the conversion of Crown land in Marylebone and St Pancras into a pleasure garden. The design work was initially assigned to the architect John Nash but it was the father and son partnership of James and Decimus Burton who had the majority of input to the project.[37] Landscaping continued through the 1820s and Regent's Park was finally opened to the public in 1841.[38]

The Zoological Society of London (ZSL) was founded in 1826 by Sir Stamford Raffles and Sir Humphry Davy. They obtained land alongside the route of the Regent's Canal through the northern perimeter of Regent's Park, between the City of Westminster and the London Borough of Camden. Following the death of Raffles soon afterwards, the 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne assumed responsibility for the project and supervised construction of the first animal houses.[39] At first, the zoo was used for scientific purposes only with admittance restricted to Fellows of the ZSL which, in 1829, was granted a Royal charter by George IV. The zoo was not opened to the public until 1847, after it became necessary to raise funds.[39]

Literature

[edit]Jane Austen, Lord Byron, Walter Scott and others were the most prominent writers of the Regency era. Especially popular forms of literature at this time were novels and poetry, such as C. F. Lawler (fl. 1812–1819)'s satirical The Regent's Bomb (The R----t's bomb! c. 1816) (published under Lawler's pseudonym Peter Pindar[a]).[40][41]

Music

[edit]Wealthy households staged their own music events by relying on family members who could sing or play an instrument. For the vast majority of people, street performers provided their sole access to music of any kind. However, the upper class enjoyed music such as Ludwig van Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 30, Felix Mendelssohn's Violin Sonata in F major, MWV Q 7, and much more.[42][43] Especially popular composers of the time included Beethoven, Rossini, Liszt, and Mendelssohn.[44]

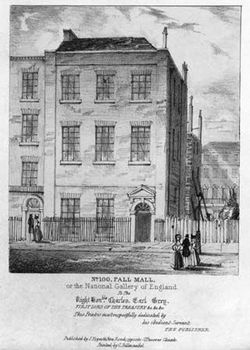

Painting

[edit]The most prominent landscape painters were John Constable and J. M. W. Turner. Notable portrait painters include Thomas Lawrence and Martin Archer Shee, both Presidents of the Royal Academy. The National Gallery was established in London in 1824.[45][46]

Theatre

[edit]

The plays of William Shakespeare were very popular throughout the period. The performers wore modern dress, however, rather than 16th-century costumes.[47]

London had three patent theatres at Covent Garden, Drury Lane and the Haymarket. Other prominent theatres were the Theatre Royal, Bath and the Crow Street Theatre in Dublin. The playwright and politician Richard Brinsley Sheridan controlled the Drury Lane Theatre until it burned down in 1809.

Media

[edit]Among the popular newspapers, pamphlets and other publications of the era were:[48]

- Ackermann's Repository

- The Gentleman's Magazine

- The Times

- The Observer

- Cobbett's Weekly Political Register

- La Belle Assemblée

In 1814, The Times newspaper adopted steam printing. Using this method, it could print 1,100 sheets every hour, five and a half times the prior rate of 200 per hour.[49] The faster speed of printing enabled the rise of daily newspapers. It also made feasible of the "silver fork novels" which depicted the lives of the rich and aristocratic. Publishers used these as a way of spreading gossip and scandal, often clearly hinting at identities. The novels were popular during the later years of the Regency era.[50]

Sport and recreation

[edit]Women's activities

[edit]During the Regency era and well into the succeeding Victorian era, society women were discouraged from exertion although many did take the opportunity to pursue activities such as dancing, riding and walking that were recreational rather than competitive. Depending on a lady's rank, she may be expected to be proficient in reading and writing, mathematics, dancing, music, sewing, and embroidery.[51] In Pride and Prejudice, the Bennet sisters are frequently out walking and it is at a ball where Elizabeth meets Mr Darcy. There was a contemporary belief that people had limited energy levels; women, as the "weaker sex", being most at risk of over-exertion because their menstruation cycles caused periodic energy reductions.[52]

Balls

[edit]One of the most common activities among the upper class was attending and hosting balls, house parties, and more. These often included dancing, food, and gossip. The food generally served included items such as white soup made with veal stock, almonds and cream, cold meats, and salads.[44]

Bare-knuckle boxing

[edit]

Bare-knuckle boxing, also known as prizefighting, was a popular sport through the 18th and 19th centuries. The Regency era has been called "the peak of British boxing" because the champion fighter in Britain was also, in effect, the world champion. Britain's only potential rival was the United States, where organised boxing began c. 1800.[53] Boxing was in fact illegal but local authorities, who were often involved on the gambling side of the sport, would turn a blind eye. In any case, the huge crowds that attended championship bouts were almost impossible to police. Like cricket and horse racing, boxing attracted gamblers. The sport needed the investment provided by gambling, but there was a seamier side in that many fights were fixed.[53]

At one time, prizefighting was "anything goes" but the champion boxer Jack Broughton proposed a set of rules in 1743 that were observed throughout the Regency era until they were superseded by the London Prize Ring Rules in 1838.[53] Broughton's rules were a reaction to "bar room brawling" as they restricted fighters to use of the fists only. A round ended when a fighter was grounded and the rules prohibited the hitting of a downed opponent. He was helped to his corner and then had thirty seconds in which to "step up to the mark", which was a line drawn for that purpose so that the fighters squared off less than a yard apart. The next round would then begin. A fighter who failed to step up and square off was declared the loser. Contests continued until one fighter could not step up.[53]

There were no weight divisions and so a heavyweight always had a natural advantage over smaller fighters. Even so, the first British champion of the Regency era was Daniel Mendoza, a middleweight who had successfully claimed the vacant title in 1792. He held it until he was defeated by the heavyweight Gentleman John Jackson in April 1795. Other Regency era champions were famous fighters like Jem Belcher, Hen Pearce, John Gully, Tom Cribb, Tom Spring, Jem Ward and James Burke.[54] Gully went on to become a successful racehorse owner and, representing the Pontefract constituency, a Member of the first post-Reform Parliament from December 1832 to July 1837.[55] Cribb was the first fighter to be acclaimed world champion after he twice defeated the American Tom Molineaux in 1811.[56][57]

Cricket

[edit]Marylebone Cricket Club, widely known as MCC, was founded in 1787 and became cricket's governing body. In 1788, the club drafted and published a revised version of the sport's rules. MCC had considerable influence throughout the Regency era and its ground, Lord's, became cricket's premier venue.[58] There were in fact three Lord's grounds. The first, opened in 1787 when the club was formed, was on the site of Dorset Square in Marylebone, hence the name of the club.[59] The lease was terminated in 1811 because of a rental dispute and the club took temporary lease of a second ground in St John's Wood.[59] This was in use for only three seasons until the land was requisitioned because it was on the proposed route of the Regent's Canal. MCC moved to a nearby site on which they established their present ground.[60]

Lord Byron played for Harrow School in the first Eton v Harrow match at Lord's in 1805.[61] The match became an annual event in the social calendar.[citation needed]

Lord's staged the first Gentlemen v Players match in 1806.[citation needed] This fixture provides another illustration of the class divide in Regency society as it matched a team of well-to-do amateurs (Gentlemen) against a team of working-class professionals (Players). The first match featured Billy Beldham and William Lambert, who have been recognised as the outstanding professionals of the period, and Lord Frederick Beauclerk as the outstanding amateur player.[citation needed] The 1821 match ended prematurely after the Gentlemen team, well behind in the contest, conceded defeat. This had been billed as the "Coronation Match" because it celebrated the accession of the Prince Regent as King George IV and the outcome was described by the sports historian Sir Derek Birley as "a suitably murky affair".[citation needed]

Football

[edit]

Football in Great Britain had long been a no-holds-barred pastime with an unlimited number of players on opposing teams which might comprise whole parishes or villages. The playing area was an undefined stretch of land between the two places. The ball, as such, was often a pig's bladder that had been inflated and the object of the exercise was to move the ball by any means possible to a distant target such as a church in the opposing village. The contests were typically arranged to take place on feast days like Shrove Tuesday.[62][63] By the beginning of the 19th century, efforts were being made in the English public schools to transform this mob football into an organised team sport. The earliest-known versions of football code rules were written at Eton College (1815) and Aldenham School (1825).[64]

Horse racing

[edit]Horse racing had been very popular since the years after the Restoration when Charles II was a frequent visitor to Newmarket Racecourse. In the Regency era, the five classic races had all been inaugurated and have been run annually since 1814. These races are the St Leger Stakes (first run in 1776), The Oaks (1779), the Epsom Derby (1780), the 2,000 Guineas Stakes (1809) and the 1,000 Guineas Stakes (1814).[65]

National Hunt racing began in 18th century Ireland and developed in England through the Regency era. There are tentative references to races held between 1792 and 1810.[66] The first definitely recorded hurdle race took place on Durdham Down, near Bristol, in 1821.[67] The first officially recognised steeplechase was over a cross-country route in Bedfordshire on 8 March 1830.[68]

Aintree Racecourse held its first meeting on 7 July 1829.[69] On 29 February 1836, a race called the Grand Liverpool Steeplechase was held. One of its organisers was Captain Martin Becher who rode The Duke to victory. The infamous sixth fence at Aintree is called Becher's Brook. The 1836 race, which became an annual event, is recognised by some as the first Grand National, but there are historical uncertainties about the three races between 1836 and 1838 so they are officially regarded as precursors to the Grand National. Some sources insist they were held on Old Racecourse Farm in nearby Maghull but this is impossible as that course closed in 1835.[70] The first official Grand National was the 1839 race.[71]

Rowing and sailing

[edit]Rowing and sailing had become popular pastimes among the wealthier citizens. The Boat Race, a rowing event between the Cambridge University Boat Club and the Oxford University Boat Club, was first held in 1829 at the instigation of Charles Merivale and Charles Wordsworth, who were students at Cambridge and Oxford, respectively. Wordsworth was a nephew of William Wordsworth. The first race was at Henley-on-Thames and the contest later became an annual event on the River Thames in London.[72] In sailing, the first Cowes Week regatta was held on the Solent in August 1826.[73]

Track and field athletics

[edit]Track and field competitions in the modern sense were first recorded in the early 19th century. They are known to have been held by schools, colleges, army and navy bases, social clubs and the like, often as a challenge to a rival establishment.[74] In the public schools, athletics competitions were conceived as human equivalents of horse racing or fox hunting with runners known as "hounds" and named as if they were racehorses. The Royal Shrewsbury School Hunt, established in 1819, is the world's oldest running club. The school organised paper chase races in which the hounds followed a trail of paper shreds left by two "foxes". The oldest running race of the modern era is Shrewsbury's Annual Steeplechase (cross-country), first definitely recorded in 1834.[75]

Events

[edit]- 1811

- George Augustus Frederick, Prince of Wales,[76] began his nine-year tenure as regent and became known as The Prince Regent. This sub-period of the Georgian era began the formal Regency. The Duke of Wellington held off the French at Fuentes de Oñoro and Albuhera in the Peninsular War. The Prince Regent held the Carlton House Fête at 9:00 p.m. 19 June 1811, at Carlton House in celebration of his assumption of the Regency. Luddite uprisings. Glasgow weavers riot.

- 1812

- Prime Minister Spencer Perceval was assassinated in the House of Commons. The final shipment of the Elgin Marbles arrived in England. Sarah Siddons retired from the stage. Shipping and territory disputes started the War of 1812 between the United Kingdom and the United States. The British were victorious over French armies at the Battle of Salamanca. Gas company (Gas Light and Coke Company) founded. Charles Dickens, English writer and social critic of the Victorian era, was born on 7 February 1812.

- 1813

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen was published. William Hedley's Puffing Billy, an early steam locomotive, ran on smooth rails. Quaker prison reformer Elizabeth Fry started her ministry at Newgate Prison. Robert Southey became Poet Laureate.

- 1814

- Invasion of France by allies led to the Treaty of Paris, ended one of the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon abdicated and was exiled to Elba. The Duke of Wellington was honoured at Burlington House in London. British soldiers burn the White House. Last River Thames Frost Fair was held, which was the last time the river froze. Gas lighting introduced in London streets.

The Battle of Waterloo by Jan Willem Pieneman, 1824. Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo - 1815

- Napoleon I of France defeated by the Seventh Coalition at the Battle of Waterloo. Napoleon was exiled to St. Helena. The English Corn Laws restricted corn imports. Sir Humphry Davy patented the miners' safety lamp. John Loudon Macadam's road construction method adopted.

- 1816

- Income tax abolished. A "year without a summer" followed a volcanic eruption in Indonesia. Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein. William Cobbett published his newspaper as a pamphlet. The British returned Indonesia to the Dutch. Regent's Canal, London, phase one of construction. Beau Brummell escaped his creditors by fleeing to France.

- 1817

- Antonin Carême created a spectacular feast for the Prince Regent at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. The death of Princess Charlotte, the Prince Regent's daughter, from complications of childbirth changed obstetrical practices. Elgin Marbles shown at the British Museum. Captain Bligh died.

- 1818

- Queen Charlotte died at Kew. Manchester cotton spinners went on strike. Riot in Stanhope, County Durham between lead miners and the Bishop of Durham's men over Weardale game rights. Piccadilly Circus constructed in London. Frankenstein published. Emily Brontë born.

- 1819

- Peterloo Massacre. Princess Alexandrina Victoria (future Queen Victoria) was christened in Kensington Palace. Ivanhoe by Walter Scott was published. Sir Stamford Raffles, a British administrator, founded Singapore. First steam-propelled vessel (the SS Savannah) crossed the Atlantic and arrived in Liverpool from Savannah, Georgia.

- 1820

- Death of George III and the accession of The Prince Regent as George IV. The House of Lords passed a bill to grant George IV a divorce from Queen Caroline, but because of public pressure, the bill was dropped. John Constable began work on The Hay Wain. Cato Street Conspiracy failed. Royal Astronomical Society founded. Venus de Milo discovered.

Places

[edit]The following is a list of places associated with the Regency era:[77]

- The Adelphi Theatre[78]

- Almack's

- Angelo's, a fencing parlor

- Apsley House

- Argyll Rooms

- Astley's Amphitheatre

- Attingham Park[79]

- Bank of England

- Bath, Somerset[80]

- Bond Street

- Brighton Pavilion

- Brighton and Hove

- Brooks's

- Burlington Arcade

- Bury St Edmunds

- Carlton House, London

- Chalk Farm Tavern

- Chapel Royal, St. James's

- Cheltenham, Gloucestershire[81]

- Circulating libraries, 1801–1825[82]

- Covent Garden

- Custom Office, London Docks

- Doncaster Races[83]

- Drury Lane

- Floris of London

- Fortnum & Mason

- Gretna Green[84]

- Gentleman Jackson's Saloon, a pugilist's parlor by bare-knuckle champion John Jackson

- Hatchard's

- Little Theatre, Haymarket

- His Majesty's Theatre

- Hertford House

- Holland House

- Houses of Parliament

- Hyde Park, London

- Jermyn Street

- Kensington Gardens[85]

- King of Clubs

- Lansdowne House

- List of gentlemen's clubs in London

- Lloyd's of London

- London Docks

- London Institution

- London Post Office[84]

- Lyme Regis

- Marshalsea, closed in 1811, new site opened in 1811 where White Lion Prison had been. Primarily a debtors' prison, also housed seditionists and political prisoners

- Mayfair, London

- Newgate Prison

- Newmarket Racecourse

- The Old Bailey

- Old Bond Street

- Opera House[86]

- Pall Mall, London

- The Pantheon

- Ranelagh Gardens

- Regent's Park

- Regent Street

- Royal Circus[86]

- Royal Opera House

- Royal Parks of London

- Rundell and Bridge jewellery firm

- Savile Row

- Somerset House

- St George's, Hanover Square

- St. James's

- Sydney Gardens, Bath[85]

- Temple of Concord, St. James's Park

- Tattersalls

- The Thames Tunnel

- Tunbridge Wells

- Vauxhall Gardens

- West End of London

- West India Docks

- Watier's

- White's

- Waterloo Bridge

Notable people

[edit]

For more names see Newman (1997).[87]

- Rudolph Ackermann

- Arthur Aikin

- Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth

- William Arden, 2nd Baron Alvanley

- Elizabeth Armistead

- Jane Austen

- Charles Babbage

- Joseph Banks

- Richard Barry, 7th Earl of Barrymore

- Henry Bathurst, 3rd Earl Bathurst

- William Beechey

- William Blake

- Beau Brummell

- Mary Brunton

- Lord Frederick Beauclerk

- Henrietta Ponsonby, Countess of Bessborough

- Marguerite Gardiner, Countess of Blessington

- Junius Brutus Booth

- Bow Street Runners

- Marc Isambard Brunel

- Caroline of Brunswick

- Frances Burney

- James Burton

- Decimus Burton

- Lord Byron

- George Campbell, 6th Duke of Argyll

- Amelia Stewart, Viscountess Castlereagh

- Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh

- George Canning

- George Cayley

- Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire

- Francis Leggatt Chantrey

- Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales

- John Clare

- Mary Anne Clarke

- William Cobbett

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- Patrick Colquhoun

- John Constable

- Elizabeth Conyngham, Marchioness Conyngham

- Tom Cribb

- John Wilson Croker

- George Cruikshank

- John Dalton

- Humphry Davy

- John Disney

- David Douglas

- Maria Edgeworth

- Pierce Egan

- Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin

- Grace Elliott

- Maria Fitzherbert

- Elizabeth Fry

- David Garrick

- George IV of the United Kingdom, Prince of Wales, Prince Regent then King

- James Gillray

- Frederick Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich

- William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville

- Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey

- Emma, Lady Hamilton

- William Harcourt, 3rd Earl Harcourt

- Ann Hatton

- William Hazlitt

- William Hedley

- Leigh Hunt

- Isabella Ingram-Seymour-Conway, Marchioness of Hertford

- Washington Irving

- John Jackson

- Edward Jenner

- Sarah, Countess of Jersey

- Dorothea Jordan

- Edmund Kean

- Charles Kemble

- John Philip Kemble

- Stephen Kemble

- Michael Kelly

- John Keats

- Lady Caroline Lamb

- Charles Lamb

- Emily Lamb, Countess Cowper

- Sir Thomas Lawrence, PRA

- Princess Lieven

- Mary Linwood

- Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

- Hudson Lowe

- Ada Byron Lovelace

- William Macready

- John Loudon McAdam

- Lord Melbourne

- Thomas Moore

- Hannah More

- John Murray

- John Nash

- Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson

- Elizabeth O'Neill

- William, Prince of Orange

- George Ormerod

- Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey

- Thomas Paine

- John Palmer, Royal Mail

- Sir Robert Peel

- Spencer Perceval

- Thomas Phillips

- William Pitt the Younger

- Jane Porter

- Hermann, Fürst von Pückler-Muskau

- Thomas De Quincey

- Thomas Raikes

- Humphry Repton

- Samuel Rogers

- Thomas Rowlandson

- James Sadler

- Walter Scott

- Richard "Conversation" Sharp

- Martin Archer Shee

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Mary Shelley

- Richard Brinsley Sheridan

- Sarah Siddons

- John Soane

- Adam Sedgwick

- Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh

- John Wedgwood

- Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

- Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley

- Amelia Stewart, Viscountess Castlereagh

- Thomas Telford

- Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford

- Joseph Mallord William Turner

- Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland

- Benjamin West

- William Wilberforce

- Harriette Wilson

- William Hyde Wollaston

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- William Wordsworth

- Jeffry Wyattville

- Thomas Young

Gallery

[edit]-

"Neckclothitania", 1818

-

Astley's Amphitheatre, 1808–1811

-

Brighton Pavilion, 1826

-

Carlton House, Pall Mall, London

-

Vauxhall Gardens, 1808–1811

-

Church of All Souls, architect John Nash, 1823

-

Regent's Canal, Limehouse, 1823

-

Frost Fair, Thames River, 1814

-

The Piccadilly entrance to the Burlington Arcade, 1819

-

Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales and Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, 1817

-

Morning dress, Ackermann, 1820

-

Water at Wentworth, Humphry Repton, 1752–1818

-

Hanover Square, Horwood Map, 1819

-

Beau Brummell, 1805

-

Battle of Waterloo, 1815

-

Almack's Assembly Room, 1805–1825

-

Balloon ascent, James Sadler, 1811

-

The Anatomist, Thomas Rowlandson, 1811

-

Regent's Park, Schmollinger map, 1833

-

100 Pall Mall, former location of National Gallery, 1824–1834

-

Cognocenti, Gillray Cartoon, 1801

-

Custom Office, London Docks, 1811–1843

-

Customs and Excise, London Docks, 1820

-

Mail coach, 1827

-

Assassination of Spencer Perceval, 1812

-

The Trial of Queen Caroline by George Hayter, 1823

-

The pillory at Charing Cross, Ackermann's Microcosm of London, 1808–1811

-

Covent Garden Theatre, 1827–1828

See also

[edit]- Regency architecture

- Regency fashions

- Regency dance

- Régence, the period of the early 18th-century regency in France

- Society of Dilettanti

- Era of Good Feelings, for the United States

Notes

[edit]- ^ The pseudonym Peter Pindar had previously been used by the satirist John Wolcot.

References

[edit]- ^ Pryde, E. B. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-5215-6350-5.

- ^ Herman, N. (2001). Henry Grattan, the Regency Crisis and the Emergence of a Whig Party in Ireland, 1788–9. Irish Historical Studies, 32(128), 478–497. [1].

- ^ "No. 16451". The London Gazette. 5 February 1811. p. 227.

- ^ Innes (1915), p. 50.

- ^ Innes (1915), p. 81.

- ^ Kendall, Paul (2022). Queen Victoria: Her Life and Legacy. Havertown: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-3990-1834-0.

- ^ Dabundo, Laura; Mazzeno, Laurence W.; Norton, Sue (2021). Jane Austen: A Companion. McFarland. pp. 177–179. ISBN 978-1-4766-4238-3.

- ^ Plunkett, John; et al., eds. (2012). Victorian Literature: A Sourcebook. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 2.

- ^ Sadleir, Michael (1927). Trollope: A Commentary. Constable & Co. pp. 17–30.

- ^ a b Hewitt, Martin (Spring 2006). "Why the Notion of Victorian Britain Does Make Sense". Victorian Studies. 48 (3): 395–438. doi:10.2979/VIC.2006.48.3.395. S2CID 143482564. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ Parissien, Steven (2002). George IV: inspiration of the Regency (1st ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-28402-2.

- ^ May, Thomas Erskine (1895). The Constitutional History of England Since the Accession of George the Third, 1760–1860. Vol. 1. pp. 263–364.

- ^ Low, Donald A. (2000). The Regency underworld (Revised ed.). Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-2121-3.

- ^ Low, Donald A. (1999). The Regency Underworld, p. x. Gloucestershire: Sutton. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Smith, E. A., George IV, p. 14. Yale University Press (1999).

- ^ "Reform Bill | British Politics, Social Change & Impact on History". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Michael Brock, The Great Reform Act (1973) online

- ^ John A. Phillips, and Charles Wetherell, "The Great Reform Act of 1832 and the political modernization of England." American Historical Review 100.2 (1995): 411–436. online

- ^ Geoffrey Finlayson, Decade of reform; England in the eighteen thirties (1970) pp.1–5. online

- ^ Boyd Hilton, A Mad, Bad, and Dangerous People?: England 1783-1846 (Oxford University Press, 2008) pp.493-558 online

- ^ Peter Dunkley, "Whigs and paupers: the reform of the English Poor Laws, 1830-1834." Journal of British Studies 20.2 (1981): 124-149.

- ^ Paul Carter, Jeff James, and Steve King. "Punishing paupers? Control, discipline and mental health in the Southwell workhouse (1836–71)." Rural History 30.2 (2019): 161–180. online

- ^ Izhak Gross, "The abolition of Negro slavery and British parliamentary politics 1832–3." The Historical Journal 23.1 (1980): 63–85.

- ^ Asa Briggs, "The Background of the Parliamentary Reform Movement in Three English Cities (1830–2)." Cambridge Historical Journal 10.3 (1952): 293–317 online.

- ^ Nob Doran, "From embodied ‘health’ to official ‘accidents’: Class, codification and British factory legislation 1831–1844." Social & Legal Studies 5.4 (1996): 523–546. online

- ^ Anna Gambles, "Rethinking the politics of protection: Conservatism and the corn laws, 1830-52." The English Historical Review 113.453 (1998): 928–952. online

- ^ Malcolm Chase, "What did Chartism petition for? Mass petitions in the British movement for democracy." Social Science History 43.3 (2019): 531-551. online

- ^ Harry Browne, Chartism (1999) online

- ^ E.A. Smith, "Charles Grey, second Earl Grey (1764–1845)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004). doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11526

- ^ G. M. Trevelyan, Lord Grey of the Reform Bill (Longman, Green, 1920) online

- ^ John Prest, Lord John Russell (1972) pp.38-54. online

- ^ W. H. Chaloner, "The Anti-Corn Law League," History Today (1968) 18#3 pp. 196–204

- ^ A. Paul Pickering, and Alex Tyrrell, The People’s Bread: A History of the Anti-Corn Law League (Leicester University Press, 2000).

- ^ Nicholas C. Edsall, The anti-poor law movement, 1834-44 (Manchester University Press, 1971) p. 9 online

- ^ K. Theodore Hoppen, The Mid-Victorian Generation 1846 to 1886 (Oxford UP, 1998)p.128.

- ^ Paul Reilly, Introduction to Regency Architecture (Braunfell Books, 2022).

- ^ Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-3043-1561-1.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica. Article on Regent's Park. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ a b "ZSL's History". Zoological Society of London. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Behrendt, Stephen C. (2012). "Was There a Regency Literature? 1816 as a Test Case". Keats-Shelley Journal. 61: 25–34. ISSN 0453-4387. JSTOR 24396032.

- ^ "Lawler, C. F.". Jackson Bibliography of Romantic Poetry. University of Toronto Libraries. Retrieved 1 September 2025.

- ^ Kerman, Joseph (1983). Beethoven. The new Grove. New York London: Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-30091-8.

- ^ Todd, Ralph Larry (2003). Mendelssohn: a life in music. Oxford: Oxford University press. ISBN 978-0-19-511043-2.

- ^ a b "A Walk Through The Regency Era". Wentworth Woodhouse. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Stephen Lloyd, "'Thomas Lawrence: Regency Power & Brilliance'." British Art Journal 11.2 (2010): 104-109.

- ^ Ian Mortimer, The Time Traveler's Guide to Regency Britain: A Handbook for Visitors to 1789–1830 (Simon and Schuster, 2022).

- ^ Tapley, Jane. Jane Austen’s Regency World Magazine, vol. 17, p. 23.

- ^ Karl W. Schweizer, "Newspapers, politics and public opinion in the later Hanoverian era." Parliamentary History 25.1 (2006): 32-48. online

- ^ Morgan, Marjorie (1994). Manners, Morals, and Class in England, 1774–1859, p. 34. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- ^ Wu, Duncan (1999). A Companion to Romanticism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-6312-1877-7.

- ^ Halsey, Katie (4 July 2015). "The home education of girls in the eighteenth-century novel: 'the pernicious effects of an improper education'". Oxford Review of Education. 41 (4): 430–446. doi:10.1080/03054985.2015.1048113. ISSN 0305-4985.

- ^ A History of Women in Sport Prior to Title IX. Richard C. Bell (2018). The Sport Journal. United States Sports Academy.

- ^ a b c d Encyclopaedia Britannica. The Bare-knuckle Era. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "The Cyber Boxing Zone Encyclopedia presents The Bare Knuckle Heavyweight Champions of England". Cyber Boxing Zone. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Miles, Henry Downes (1906). Pugilistica: the history of British boxing containing lives of the most celebrated pugilists. Edinburgh: John Grant. pp. 182–192. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Pierce Egan, Boxiana, Volume I (1813).

- ^ Snowdon, David (2013). Writing the Prizefight: Pierce Egan's Boxiana World.

- ^ Warner, Pelham (1946). Lord's 1787–1945. Harrap. pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Warner, p. 18.

- ^ Warner, p. 19.

- ^ Williamson, Martin (18 June 2005). "The oldest fixture of them all: the annual Eton vs Harrow match". Cricinfo Magazine. London: Wisden Group. Retrieved 23 July 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Dunning, Eric (1999). Sport Matters: Sociological Studies of Sport, Violence and Civilisation. Routledge. p. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-415-09378-1.

- ^ Baker, William (1988). Sports in the Western World. University of Illinois Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-252-06042-7.

- ^ Cox, Richard William; Russell, Dave; Vamplew, Wray (2002). Encyclopedia of British Football. Routledge. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-7146-5249-8.

- ^ Fletcher, J. S. (1902). The history of the St Leger stakes, 1776–1901. Hutchinson & Co. ISBN 978-0-9516-5281-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Barrett, Norman, ed. (1995). The Daily Telegraph Chronicle of Horse Racing. Enfield, Middlesex: Guinness Publishing. pp. 9–12.

- ^ Barrett, p. 12.

- ^ Sporting Magazine (1830), May and July editions.

- ^ "And they're off – a brief history of Aintree racecourse and the Grand National". Age Concern Liverpool & Sefton. 9 April 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Birth of The Grand National: The Real Story". Mutlow, Mick (15 June 2009). Thoroughbred Heritage. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Wright, Sally (3 April 2020). "An early history of Aintree racecourse". Timeform.

- ^ "The Boat Race origins". The Boat Race Limited. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Icons, a portrait of England 1820–1840". Archived from the original on 22 September 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ History – Introduction Archived 1 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine. IAAF. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Robinson, Roger (December 1998). "On the Scent of History". Running Times: 28.

- ^ "George IV (r. 1820–1830)". The Royal Household. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Newman, Gerald, ed. (1997). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-0396-1.

- ^ Nelson, Alfred L.; Cross, Gilbert B. "The Adelphi Theatre, 1806–1900". Archived from the original on 8 June 2007.

- ^ "Attingham Park: History". National Trust. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Roman, Regency and really nearby". The Daily Telegraph. London. 14 April 2006. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ Sanders, Stephanie (6 December 2013). "Explore the Regency spa town of Cheltenham". visitengland.com.

- ^ "Circulating Libraries, 1801–1825". Library History Database. Archived from the original on 14 April 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Jane Austen: Sports". Jane's Bureau of Information. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Jane Austen: Places". Jane's Bureau of Information. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Jane Austen: Gardens". Jane's Bureau of Information. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Jane Austen: Theatre". Jane's Bureau of Information. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Newman, Gerald, ed. (1997). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-0396-1.

Sources

[edit]- Bowman, Peter James. The Fortune Hunter: A German Prince in Regency England. Oxford: Signal Books, 2010. [ISBN missing]

- David, Saul. Prince of Pleasure The Prince of Wales and the Making of the Regency. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1998. [ISBN missing]

- Innes, Arthur Donald (1914). A History of England and the British Empire. Vol. 3. The MacMillan Company.[ISBN missing]

- Innes, Arthur Donald (1915). A History of England and the British Empire. Vol. 4. The MacMillan Company.[ISBN missing]

- Knafla, David, Crime, punishment, and reform in Europe, Greenwood Publishing, 2003 [ISBN missing]

- Lapp, Robert Keith. Contest for Cultural Authority – Hazlitt, Coleridge, and the Distresses of the Regency. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1999. [ISBN missing]

- Marriott, J. A. R. England Since Waterloo (1913) online

- Morgan, Marjorie. Manners, Morals, and Class in England, 1774–1859. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994. [ISBN missing]

- Morrison, Robert. The Regency Years: During Which Jane Austen Writes, Napoleon Fights, Byron Makes Love, and Britain Becomes Modern. 2019, New York: W. W. Norton, London: Atlantic Books online review

- Newman, Gerald, ed. (1997). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714–1837: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-0396-1. online review; 904pp; 1121 short articles on Britain by 250 experts.

- Parissien, Steven. George IV Inspiration of the Regency. New York: St. Martin's P, 2001. [ISBN missing]

- Pilcher, Donald. The Regency Style: 1800–1830 (London: Batsford, 1947).

- Rendell, Jane. The pursuit of pleasure: gender, space & architecture in Regency London (Bloomsbury, 2002). [ISBN missing]

- Richardson, Joanna. The Regency. London: Collins, 1973. [ISBN missing]

- Webb, R.K. Modern England: from the 18th century to the present (1968) online widely recommended university textbook

- Wellesley, Lord Gerald. "Regency Furniture", The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 70, no. 410 (1937): 233–241.

- White, R.J. Life in Regency England (Batsford, 1963). [ISBN missing]

Further reading

[edit]- Adkins, Roy, and Lesley Adkins. Jane Austen's England: Daily Life in the Georgian and Regency Periods (Penguin, 2013) online.

- Arora, Vidusha. "Regency England through the Realistic Lens of Jane Austen." Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) 11.1 (2023): 230-234. online

- Ashton, John. When William IV. Was King: Exploring the Regency Era Through King William IV's Reign (Good Press, 2021) online.

- Behrendt, Stephen C. "Was There a Regency Literature? 1816 as a Test Case." Keats-Shelley Journal 61 (2012): 25-34. online

- Bruley, Katherine. "Fashion in the Regency Era." The Boller Review 6 (2021). online

- Carr, Hannah Merryl. "In Revenge He Has Taken the Stays: Dandyism and Social Othering in Regency Newspapers, 1814-1818" (PhD dissertation, Carleton University, 2024) online.

- Cohen, Ashley L. "The 'Aristocratic Imperialists' of Late Georgian and Regency Britain." Eighteenth-Century Studies 50.1 (2016): 5-26. online

- Emsley, Clive. Crime and society in England: 1750–1900 (2013).

- Hobson, James. Dark Days of Georgian Britain: Rethinking the Regency (Pen and Sword, 2019) online.

- Hughes, Kristine. The Writer's Guide to Everyday Life in Regency and Victorian England from 1811-1901 (1997) online

- Innes, Joanna and John Styles. "The Crime Wave: Recent Writing on Crime and Criminal Justice in Eighteenth-Century England" Journal of British Studies 25#4 (1986), pp. 380–435 JSTOR 175563.

- Low, Donald A. The Regency Underworld. Gloucestershire: Sutton, 1999.

- Mitton, Geraldine Edith. Jane Austen and Her Times: Exploring Jane Austen's World and Works in Regency England (Good Press, 2021) online.

- Morgan, Gwenda, and Peter Rushton. Rogues, Thieves And the Rule of Law: The Problem of Law Enforcement in North-East England, 1718–1820 (2005).

- Sari, Yuliana Kartika, and Syahara Dina Amalia. "Representation of Regency Era in 'Emma'(2020) Movie: a Sociological Perspective." Proceeding ISETH (International Summit on Science, Technology, and Humanity) (2023): 485-497. online

Primary sources

[edit]- Evans, Eric J. ed. Britain Before the Reform Act: Politics and Society 1815–1832 (Longman, 1989

- Gash, Norman, ed. The Age of Peel (1968) online

- Revill, P. ed. The Age of Lord Liverpool (Blackie, 1979)

- Simond, Louis. Journal of a tour and residence in Great Britain, during the years 1810 and 1811 online

External links

[edit]- Greenwood's Map of London, 1827

- Horwood Map of London, 1792–1799

- Results of the 1801 and 1811 Census of London, The European Magazine and London Review, 1818, p. 50

- The Bluestocking Archive

- End of an Era: 1815–1830

- New York Public Library, England – The Regency Style

- Regency Style Furniture Archived 14 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine